Skylark: The unsung hero of British space

- Published

From the archive, 2005: The final mission launched from Sweden

It's 60 years to the day that Britain launched its first Skylark rocket.

It wasn't a big vehicle, and it didn't go to orbit. But the anniversary of that first flight from Woomera, Australia, should be celebrated because much of what we do in space today has its roots in this particular piece of technology.

"Skylark is an unsung British hero really," says Doug Millard, space curator at London's Science Museum, external.

"The first one was launched during the International Geophysical Year of 1957, and almost 450 were launched over the better part of half a century. It was the Skylark space rocket that really laid the foundations for everything the UK does in space."

Millard is opening a corner of the museum's Space Gallery to the memory of the Skylark.

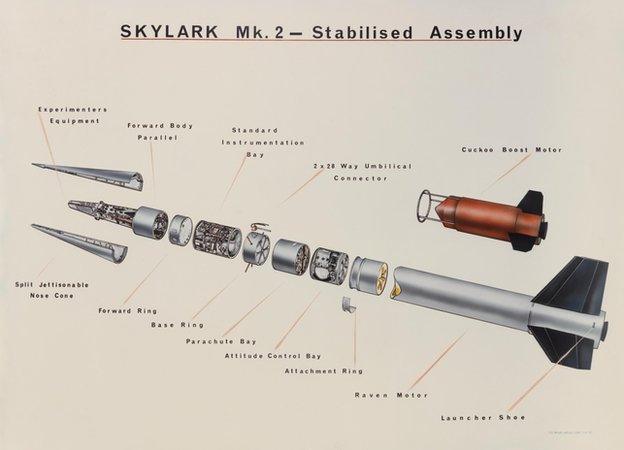

It contains old rocket components and illustrations of the type of work in which the vehicle became engaged.

That year, 1957, also saw the launch of the first satellite, the Soviets' Sputnik, so we really are talking about the beginning of the "space race".

Skylark was what is called a sounding rocket. It would go just fast enough and high enough - a few hundred kilometres - to gather new data on the upper atmosphere or to observe space and its unique environment.

At the top of the rocket's climb, for example, experiments would get a few minutes to sample what happens in weightlessness.

Skylark was doing important pathfinder work on the UK's Blue Streak nuclear missile programme. And it was also performing novel types of astronomy by carrying up instruments that could sense deep space in ways that simply weren't possible from the ground.

Many of the young researchers who cut their teeth on these early endeavours would go on to define British space activity in the years ahead.

"Almost all that I know about rocket science, I learnt from the Skylark programme," says John Zarnecki, who later worked on the Giotto comet-chaser, the Hubble space telescope, and the Huygens probe to Titan.

"The Skylark programme gave PhD students like myself the opportunity to be real rocket scientists. We were given enormous responsibility to run a small space project from the very start.

"The Skylark programme gave access to space for only a few minutes at a time. But it gave us a glimpse of the electromagnetic spectrum beyond the visible and helped to lay the foundations of the 'new astronomies', such as X-ray and ultraviolet which were to have such a major impact on astronomy over the last 50 years."

Another Skylark veteran is Chris Rapley, a former director of the British Antarctic Survey and of the Science Museum itself.

In the 1970s, he too was a PhD astronomer, at the Mullard Space Science Laboratory.

"The short timescales from proposing a Skylark mission to its launch - sometimes as little as two years - allowed new ideas and new technologies to be exploited on human timescales, and invoked a real sense of purpose and accomplishment.

"The downside was that the failure rate could be quite high. But the MSSL Director Prof Boyd (later Sir Robert Boyd) memorably said: 'If we are not suffering failures, we are not working at the edge, and if we are not working at the edge, we shouldn't be here'. It was more than career-forming; it was life-forming."

Skylark was developed by the Royal Aircraft Establishment in Farnborough, in conjunction with the Rocket Propulsion Establishment at Westcott.

The solid-fuel, plastic propellant motors were prepared by the Royal Ordnance Factory Bridgwater.

One the preparation testing consoles is in the new Science Museum exhibition.

"It's just a riot of bakelite, dials, knobs and switches - it's real, unadulterated boffin territory," says Doug Millard.

Doug Millard: Testing console was "a riot of bakelite, dials, knobs and switches"

Having been enthusiastically supported at the outset, the programme eventually lost favour in Whitehall and the last motors came off the production line in 1994.

That wasn't an immediate end for Skylark because enough components had been stockpiled that flights could be continued through to 2005.

The very last mission, on 2 May that year, was recorded by the BBC.

You can see my colleague David Shukman's archive report from the Esrange space centre in Sweden on this page.

In many ways, the Skylark's story mirrors that of British space activity itself: pioneering early days that were then followed by a period of neglect and decline.

But as we remember this 60th anniversary, it's good to see UK space activity again in the ascendant. And it's remarkable to think rockets are once more being developed in this country.

There are perhaps a dozen different projects being marshalled by start-ups right now.

I can't say how many, if any, will match the 441 launches of the Skylark, but it's important to realise that spirit hasn't gone away.

Old footage of the Skylark rocket and its preparation

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external