RemoveDebris: Space junk mission prepares for launch

- Published

A spacecraft will test clean-up technologies after it launches next year

A mission that will test different methods to clean up space junk is getting ready for launch.

The RemoveDebris spacecraft will attempt to snare a small satellite with a net and test whether a harpoon is an effective garbage grabber.

The probe has been assembled in Surrey and will soon be packed up ready for blast off early next year.

Scientists warn that the growing problem of space debris is putting spacecraft and astronauts at risk.

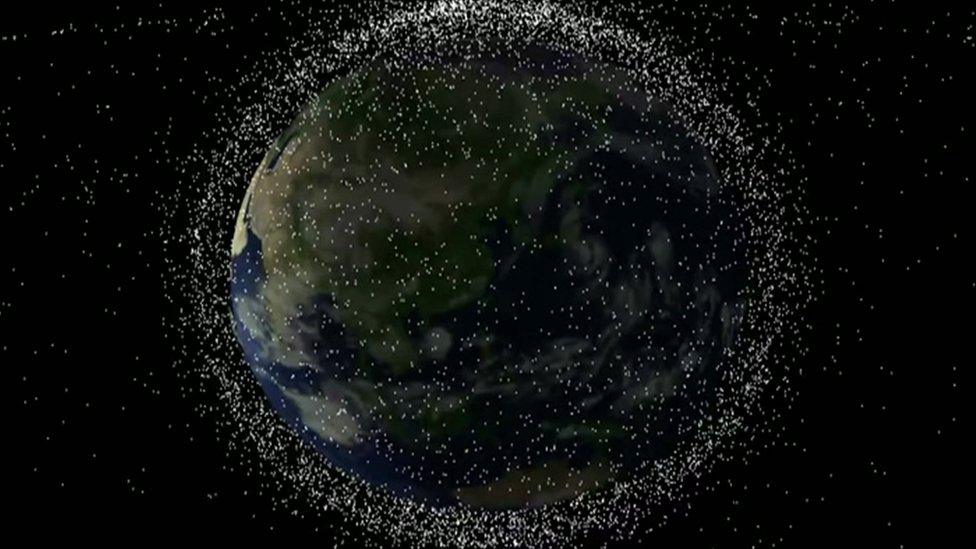

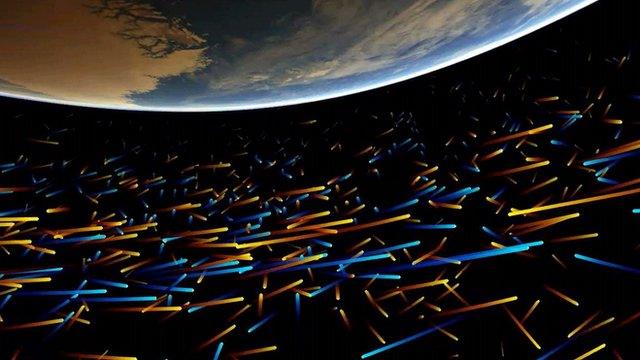

It is estimated that there are about half a million pieces of man-made rubbish orbiting the Earth, ranging from huge defunct satellites, to spent rocket boosters and nuts and bolts.

Any collisions can cause a great deal of damage, and generate even more pieces of debris.

The RemoveDebris mission is led by the Surrey Space Centre at the University of Surrey.

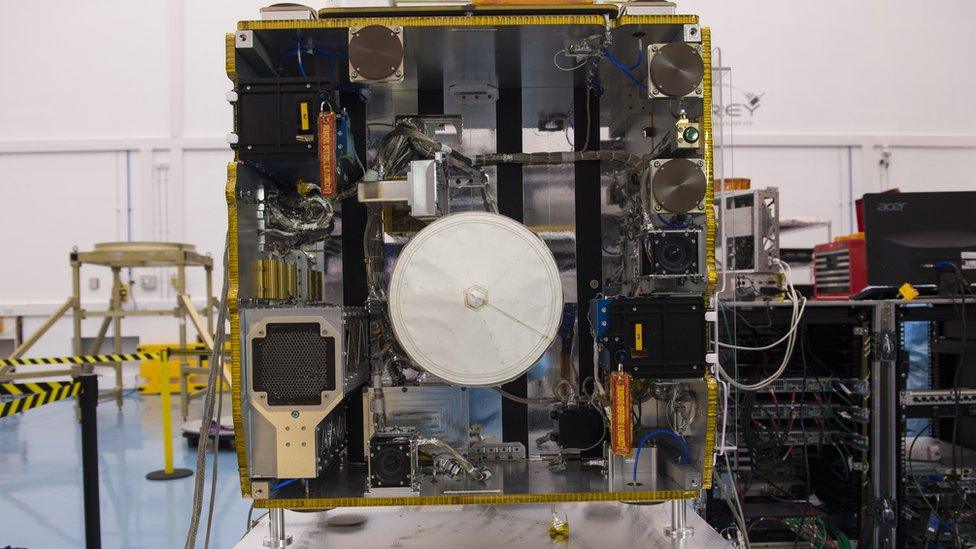

The assembly of the spacecraft, which is about the size of a washing machine, has taken place at Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd (SSTL) and is almost complete.

Dr Jason Forshaw, project manager on the RemoveDebris team, said: "RemoveDebris will be one of the world's first missions in this area.... We have technologies on here that have never been demonstrated in space before."

The spacecraft has been assembled in the UK and will soon be packed up for launch

The spacecraft will first head for the International Space Station on a resupply rocket.

It will then be unpacked by astronauts before being launched from the orbiter to begin its experiments.

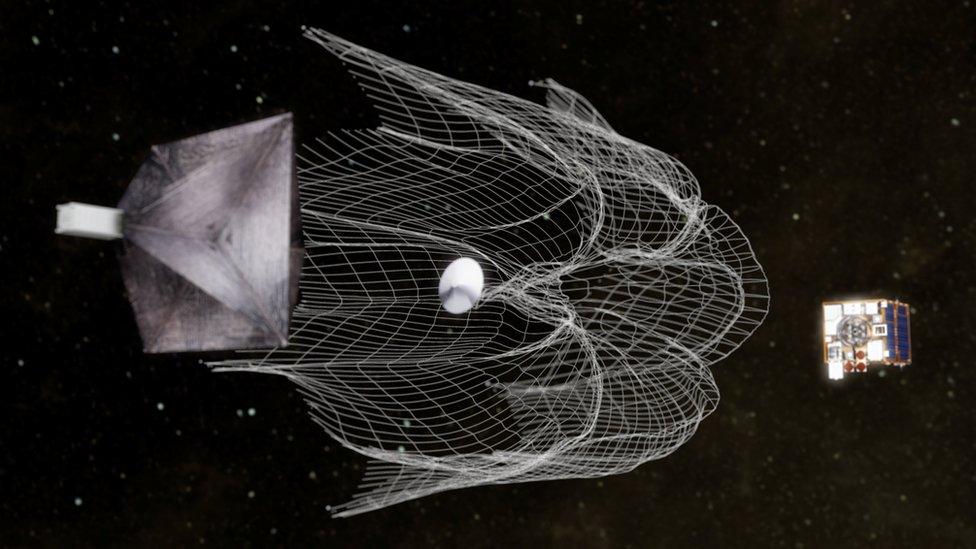

RemoveDebris has its own space junk on board - small satellites. It will release one of these into space and then will use a net to recapture it.

It will also fire a small harpoon at a target plate to see if the technology can accurately work in the weightless environment.

It will finally test future de-orbiting technology. As the orbiter descends to Earth it will deploy a 10sq m sail, which will change the spacecraft's speed and ensure it burns up as it enters the atmosphere.

"It will prevent the spacecraft from becoming space junk itself," explained Dr Forshaw.

The hope is that the technology-testing mission, which has cost £15m, will lead to larger clean-up efforts.

"People are starting to realise the significance of space junk and the problem it presents," Dr Forshaw said.

The spacecraft will establish whether a net could ensnare a small satellite

Scientists estimate that there are about 7,500 tonnes of rubbish in space and we are reaching a critical point. .

Dr Hugh Lewis, senior lecturer in aerospace engineering at the University of Southampton, said: "For some people, space debris is one of these things that is out of sight, out of mind.

"But from my perspective it is one of the worst environmental catastrophes that we have encountered."

Even very small pieces of junk can do a great deal of damage.

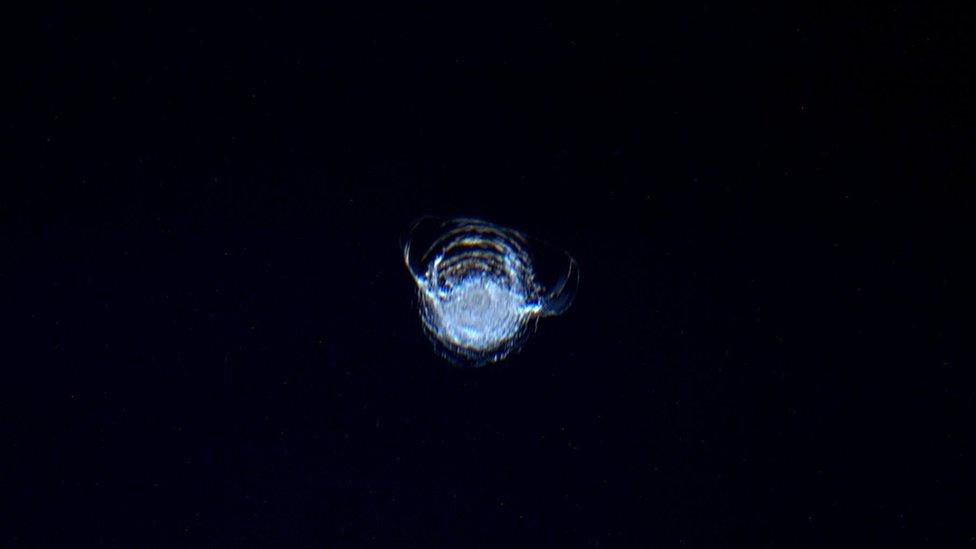

Last year a loose fleck of paint is thought to have caused a crack in a window on the International Space Station.

Last year a small piece of debris chipped a window on the International Space Station

The largest pieces, though, present a pressing problem.

In 2012, a European satellite called Envisat, the size of a double decker bus, suddenly stopped working.

Since then it's been circling the Earth, threatening other key satellites in its path.

Dr Lewis explained: "The biggest pieces of space debris have huge amounts of mass in them. If they were to be hit by something, they would release all that mass in the form of thousands and thousands of more fragments."

More debris, could lead to more collisions - a cascade effect known as the Kessler syndrome. The fear is that space could eventually become inoperable.

"The environment provides us with really important services - like navigation, timing, communications, weather forecasting and so on," Dr Lewis added.

"The worst case scenario is probably the loss of some vital satellites… it would mean stepping back probably decades in terms of our technology we take for granted on Earth."

It is estimated that there are about half a million pieces of space junk the size of a marble or larger

The European Space Agency is now looking at how larger satellites like Envisat can be destroyed - but cleaning up space piece by piece will be difficult and extremely expensive.

International space guidelines suggest that satellites should de-orbit themselves after 25 years - but it is difficult to ensure everyone plays by the rules.

Some experts are also concerned that the new push to launch small satellites (known as cubesats) in increasingly large numbers could add to the problem.

Martin Pointer from SSTL said: " Space junk is definitely a concern for us. As more and more satellites are put up - especially some of the constellations of small satellites - the likelihood of collisions is much greater.

"I think it's our responsibility to ensure we don't cause more junk in space and find ways of either removing those at the end of life or for mitigating against problems."

Follow Rebecca on Twitter., external

- Published8 April 2017

- Published9 December 2016

- Published5 August 2015

- Published18 April 2017