The other Dodo: Extinct bird that used its wings as clubs

- Published

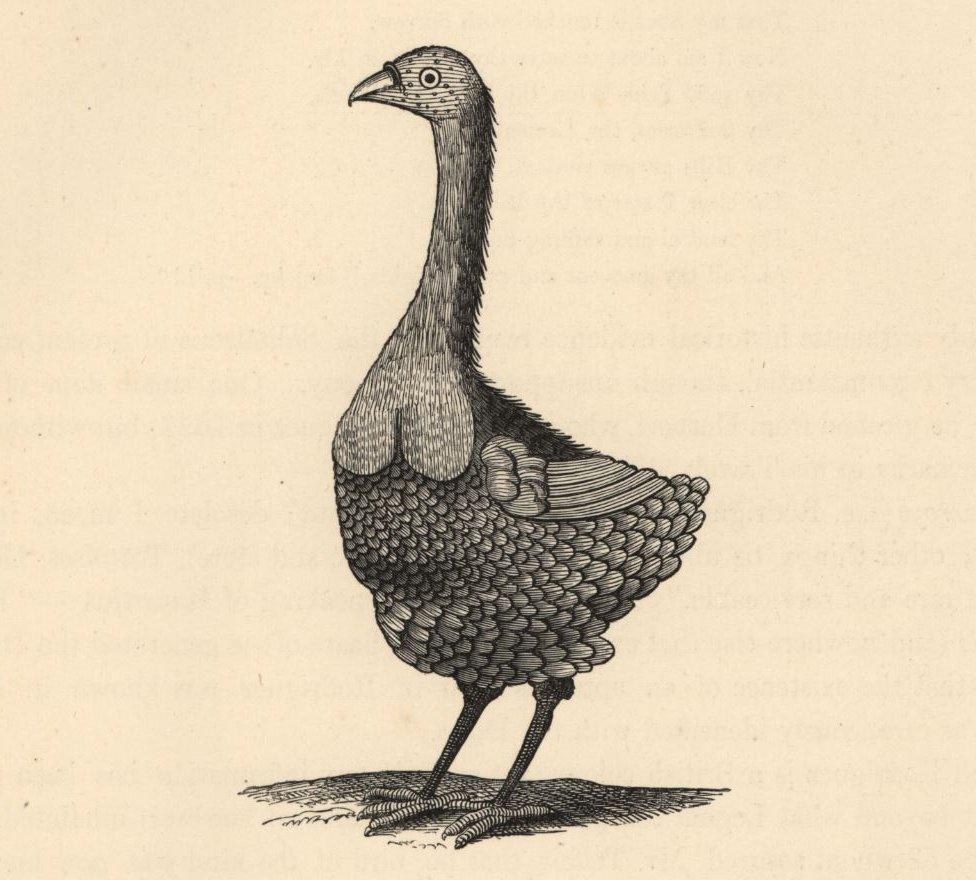

Two male Rodrigues solitaires fight over a female in the background using club-like wings

The extinct Dodo had a little-known relative on another island. This fascinating bird ultimately suffered the same fate as its iconic cousin, but we can reconstruct some of its biology thanks to the writings of a French explorer who studied it during his travels of the Indian Ocean.

In the middle of the 18th Century, at around the time the US was signing the declaration of independence, a large flightless bird quietly became extinct on an island in the Indian Ocean.

Today this bird is all but forgotten.

Early explorers to Rodrigues described a "Dodo" living on the tiny forested island. Males were grey-brown, and females sandy, both having strong legs and long, proud necks. But despite outward similarities to the iconic Mauritian bird, this wasn't in fact a Dodo, but the Rodrigues solitaire.

If you look up Rodrigues in satellite images, you can see a huge ring of submerged land around the central island, over 50% of the original dry land is thought to have been lost under the waves due to sea-level rise and the island subsiding into the bedrock.

That was the stage for the evolution of the huge bird, over millions of years.

The small island of Rodrigues is part of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean

It's likely this shrinking habitat caused an increase in competition for food and territory between individuals of the species, and perhaps as a result of this, the solitaire evolved a club-like bone growth on the end of each wing.

It used this against other solitaires in territorial boxing matches. These would have been quite a sight, as the males stood almost a metre tall and weighed nearly 30kg, while the females were sandy-coloured and were half that size.

Considering its obscurity today, we have amazingly detailed descriptions of the solitaire's behaviour.

This is because of the diary of a man named François Leguat.

He was part of a group of seven Huguenot men, who had set out from France to establish a colony of French protestant refugees on the island of Reunion.

Instead, they were marooned for two years on the island of Rodrigues from 1691 to 1693. In that time, they made the first attempts at establishing a settlement on the island.

Leguat encountered the solitaire in this time and wrote about it in his diary:

"Of all the birds in the island the most remarkable is that which goes by the name of the solitary, because it is very seldom seen in company, tho' there are abundance of them… Its eye is black and lively, and its head without comb or cop. They never fly, their wings are too little to support the weight of their bodies; they serve only to beat themselves, and flutter when they call one another."

Francois Leguat was marooned on the island of Rodrigues in 1601 where he encountered, described and drew the forgotten Rodrigues solitaire

Leguat described how the birds used their short wings to make a loud rattling sound that could be heard "two hundred paces off".

He also described the bone on their wing which grew larger at the end, forming a mass under the feathers "as big as a musket ball".

This was used as a club-like weapon, and along with their beak, was "the chief defence of this bird".

These are tantalising clues showing us what the species was like in life, and are some of the first detailed behavioural descriptions of any bird. It's likely that the rattling sounds were used both to attract the attention of a mate and as a warning to same-sex rivals, but it's highly unusual for birds to use their wings to make sounds for long-distance communication, making even more acute the loss of such a unique animal.

The solitaire would have been quite striking in life, and in his writings it is clear Leguat had some affection for them: "No one feather is straggling from the other all over their bodies, they being very careful to adjust themselves, and make them all even with their beaks. "

Today, we have numerous bone remains of the species, and these come from caves and deposits across the island.

They can be found reconstructed in museums on the island and elsewhere, but there are no records of a live specimen leaving the island, and there are no preserved skins of the animal left.

Studying these bones, scientists, including extinct bird expert Dr Julian Hume, have noticed an abundance of healed bone fractures on the sternum and wings.

Comparing these with Leguat's descriptions, he theorises that the birds would frequently hit each other so hard with their wing-clubs that they were breaking the bones of their rivals.

So these descriptions from the marooned Huguenot are incredibly valuable, allowing us to interpret the specimens we have left.

They even show the breeding behaviour of the bird, which was likely monogamous:

"They never lay but one egg, which is much bigger than that of a goose. The male and female both cover it in their turns, and the young is not hatch'd till at seven weeks' end: All the while they are sitting upon it, or are bringing up their young one, which is not able to provide itself in several months."

The Victoria crowned pigeon is the biggest living pigeon species, closely related to the solitaire, it has a growth on the wing-wrist that it uses for defence

Monogamy and shared parental care are common in other pigeons we see today, including close living relatives of the solitaire: the nicobar pigeon and crowned pigeons.

Like these pigeons, the solitaires likely fed their chicks "pigeon milk", a nutrient rich soup produced in the walls of the throat pouch of the parent birds.

Two parents are able to produce more food, and so a larger chick, increasing their competitive advantage against other birds in the fight for territory.

Parts of the behaviour of the solitaire described by Leguat, including the aggression, can be seen in the crowned pigeons, which will hit anything that approaches them on the nest with small bone spurs on their wing-wrists.

But in the solitaire, with its evolutionary cauldron of the shrinking island of Rodrigues, these adaptations were pushed to an extreme.

The story of the solitaire may sound like deja vu. When Leguat and his fellow castaways eventually escaped Rodrigues on a cobbled together raft, they drifted 200 miles to Mauritius, the island home of the Dodo.

This was strangely coincidental because 1693 was the very year that the Dodo is thought to have gone extinct.

Sadly, it meant that he couldn't put his descriptive writing to work on the solitaire's better known relative. Yet despite this, today the comically described Dodo is far better known than its elegant relative.

That's likely because it was initially thought the solitaire was a Dodo living on Rodrigues.

Early observers on Rodrigues called the solitaire the "Rodrigues Dodo". But the two birds were really subtly different evolutionary outcomes to similar selective pressures and, as such, represent an incredible experiment in evolution.

The two birds were, however, close cousins.

Paradise island: Rodrigues today

Both birds descended from a small species of pigeon that likely flew to the islands about 10 million years ago.

On arrival, they found an abundance of food and an absence of predators on both islands.

This was a fruit-eating pigeon's paradise, so flying became unnecessary, and they lost the ability in favour of larger size. This is where the biology of the bird challenges some recent scientific dating of the rocks of the island.

Genetic evidence suggests a gap of around 12 million years between the last gene exchange between the Dodo and the solitaire, while some rocks dated on Rodrigues suggest the island is 1.5 million years old.

Dr Julian Hume suggests it is likely the species island-hopped down to the Mascarene islands before becoming genetically isolated due to the loss of flight on the islands some 12 million years ago, showing how the age of the island is in dispute.

Despite arising in very similar environments, the two birds evolved different adaptations for the same problems.

The Dodo, on the larger island of Mauritius, had a much larger beak with a hooked tip. Dr Hume believes that they probably used that bill to hit each other in territorial disputes.

So it's quite possible that the Dodo was similar to the solitaire in being highly aggressive and territorial, yet lacking the specific adaptation of the rattling clubbed-wings for defence.

In fact, the Dodo's wings were tiny and it's thought they were used just for balance.

We have no descriptions from life of how the Dodo reproduced, but Leguat wrote that the solitaire laid a single egg on a nest raised off the ground on pine leaves.

It's likely the Dodo behaved in a very similar way, and bird palaeontologists now think this was the Achilles heel of both species.

Mauritius had been settled by the early Portuguese and then Dutch mariners as a stop-off on their trading journeys. These groups brought rats, cats and domestic pigs with them to the island, and these were left to run feral.

Unfortunately, the large single egg of the Dodo was a perfect feast for the invading mammals, and despite their formidable ability to fight each other for territory, they had lost any instinct to protect their egg against these invaders.

Likewise the solitaire. It was protected for a hundred years by the isolation of its remote and tiny island, but, ultimately, a combination of development, rats, and cats sent the other Dodo to the same fate.

This article was inspired by research for the radio documentary 'Can we revive extinct species like the Dodo?' CrowdScience was on the BBC World Service at 20.35 on Friday 1 December, or afterwards you can download the CrowdScience Podcast to listen on demand.