How dinosaur scales became bird feathers

- Published

Birds and alligators are closely related, both belonging to the Archosaur group

The genes that caused scales to become feathers in the early ancestors of birds have been found by US scientists.

By expressing these genes in embryo alligator skin, the researchers caused the reptiles' scales to change in a way that may be similar to how the earliest feathers evolved.

Feathers are highly complex natural structures and they're key to the success of birds.

But they initially evolved in dinosaurs, birds' extinct ancestors.

Leading the study, Professor Cheng-Ming Chuong told the BBC that this discovery links important recent palaeontological finds with modern biology, in understanding feather evolution.

Birds have had feathers for as long as they have existed as a group and Professor Chuong couldn't study primitive examples of feathers in any living animals.

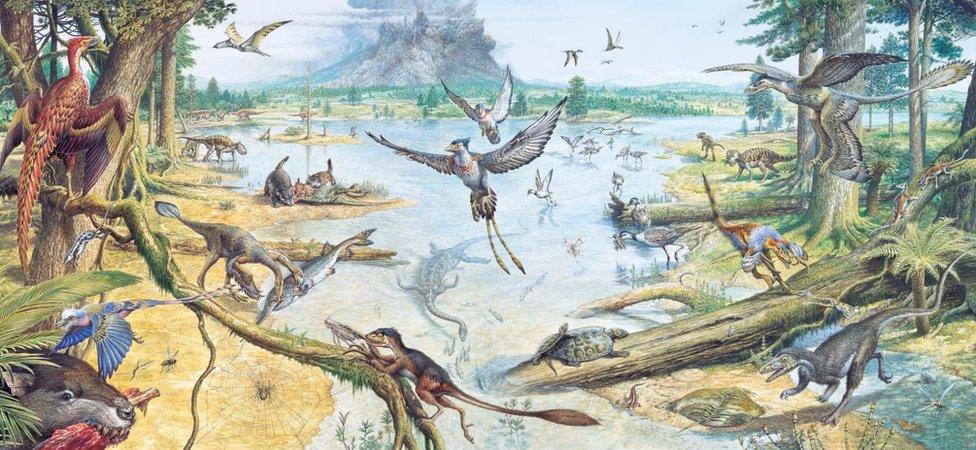

Feathers evolved in dinosaurs: birds were a group of dinosaurs that evolved flight and survived the Cretaceous mass extinction

"In today's existing reptiles, the one more similar to dinosaurs is actually the alligator, belonging to the Archosaur group," said Prof Chuong from the University of Southern California, in Los Angeles.

Dinosaurs and birds also belong to this wider group of "Archosaur reptiles"; Prof Chuong wanted to investigate whether the feather-forming genes he had identified in birds could change those scales into feathers. So he set out to turn on these genes in the skin of alligator embryos.

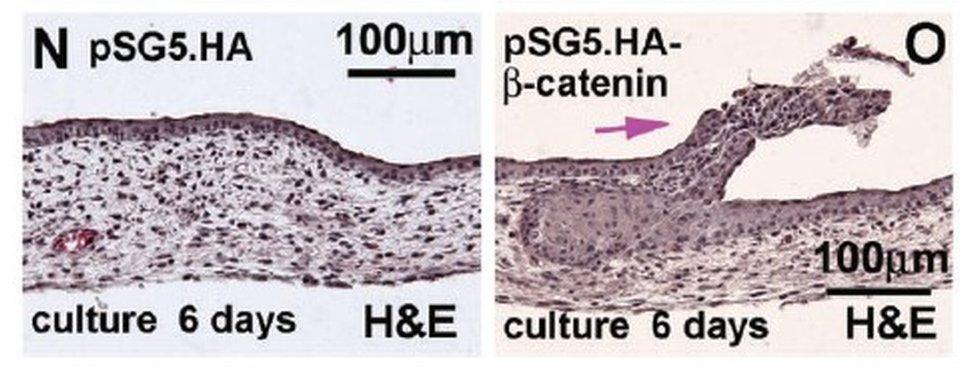

"You can see we can indeed induce them to form appendages, although it is not beautiful feathers, they really try to elongate" he explained of the outcome. They are likely similar to the structures on those feather-pioneering dinosaurs 150 million years ago.

The reason the gene doesn't cause the development of a fully feathered alligator is that unlike birds, alligators don't have the underlying genetic architecture evolved to support these central feather-making genes, or hold the structures in place on the skin.

Normal embryonic scales (L) compared with the elongated scales after genetic modification (R)

But the team's research does provide evidence for how early dinosaurs initiated the development of feathers.

In recent years, palaeontologists have found evidence of "proto feathers" in a huge range of different dinosaur species.

"Feathered dinosaurs have unusual so called proto-feathers… it looks like they have feathers but the feathers are not identical to today's (bird) feathers."

Some of these were very simple structures, without the branching complexity seen in birds today. We now know that many dinosaurs were warm blooded like birds and mammals, this meant that they could save energy by holding onto heat produced in their bodies. Scales are not good at this, and so there was a selective pressure to develop something like fur.

Feathers are highly complex natural structures

As with mammalian fur, the early single-shafted feather growths prevented heat being conveyed away from the body in the air. But unlike fur, proto-feathers became more complex over evolutionary time, branching off with side veins and barbs, and developing extraordinary colours.

Today, feathers are phenomenally useful to birds, and not just because they allow flight.

Alongside the strong asymmetrical flight feathers, there are fluffy downy feathers that keep the animals warm, but in many birds, there are also feathers that grow continuously and break down into a powder that waterproofs the other feathers to keep them dry and buoyant. In others, long wire-like feathers grow like whiskers all over the body and feedback information about air-flow in the sky.

Many of these extraordinary feather structures had already developed in their late ancestor dinosaurs. This was necessarily the case, because the complex, strong, asymmetrical feathers that are necessary for powered or even gliding flight in birds, existed at in the very first known bird ancestor, archaeopteryx, and all modern birds descended from a flying ancestor.

A diverse range of feathers enable birds to exploit different roles from attracting mates, to hovering or floating

But flight was just one highly successful experiment with feathers.

Modern feathers involve a range of different genes working together and being expressed at the right time and in the right space during the embryo's development. This new work helps to establish how feathers initially evolved, around 120 to 150 million years ago, but hints at five separate genetic processes active in birds that needed to work together to create modern feathers.

"In human evolution the great achievement is the brain, in birds it is the feathers," says Prof Chuong. Today his research is opening the door to understand how such a great achievement came about.

There are practical implications of Prof Chuong's work. His team is working with plastic surgeons to help understand why skin structures don't develop well on scar tissue.

This research informs our understanding of the process of how skin creates the structures that interact with the outside environment. With a better understanding of this, regenerative therapies could help people get better after accidents.

The study is published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, external.

Follow Rory on Twitter., external