River departed 'before Indus civilisation emergence'

- Published

Drilling sediments in the Ghaggar-Hakra palaeo-channel

Further light has been shed on the emergence and demise of one of the earliest urban civilisations.

The Indus society came to prominence in what is now northwest India and Pakistan some 5,300 years ago thanks in large part to the sustenance of a long-lost Himalayan river.

Or so it was thought.

New evidence now indicates this great water course had actually changed its path and disappeared before the Indus people had even settled in the region.

That they lacked the resource offered by a big, actively flowing river will come as a surprise to many; the other early urban societies of the time, in Egypt and Mesopotamia, certainly benefitted in this way.

The new research was led from the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur and from Imperial College London.

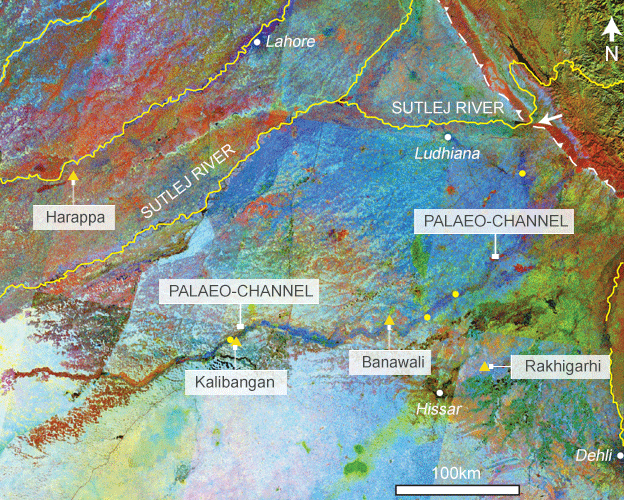

Infrared satellite imagery picks out the distinctive sediments of the ancient channel

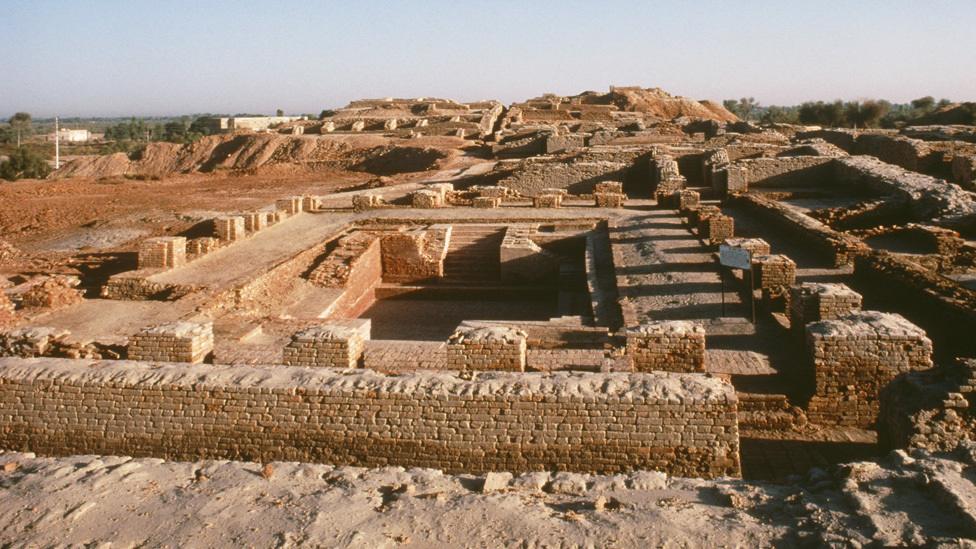

Remnant of a street in the urban centre of Kalibangan

The group's scientists do not disagree that the Bronze Age settlements would have needed a good water supply, but argue that this requirement could have been met instead by seasonal monsoon rains that still collected and ran through the valley abandoned by the old river.

"Our paper clearly demolishes the age-old river-culture hypothesis that assumed that the disappearance of the river triggered the demise of the Harappan civilisation," said IITK's Prof Rajiv Sinha.

"We have argued that while large rivers have important connections with ancient societies, it is their departure that controls their stabilisation rather than their arrival.

"This has clearly been demonstrated by the large difference in age data between the demise of the river (8,000-12,000 years ago) and the peak of mature civilisation (3,000-4,000 years ago)," he told BBC News.

Prof Sinha and colleagues report their findings in this week's Nature Communications journal, external.

A collection of mineral grains that helped trace the origin of the palaeo-river

They have examined afresh the course of what is referred to as the Ghaggar-Hakra palaeo-channel, from satellite data and from field investigations.

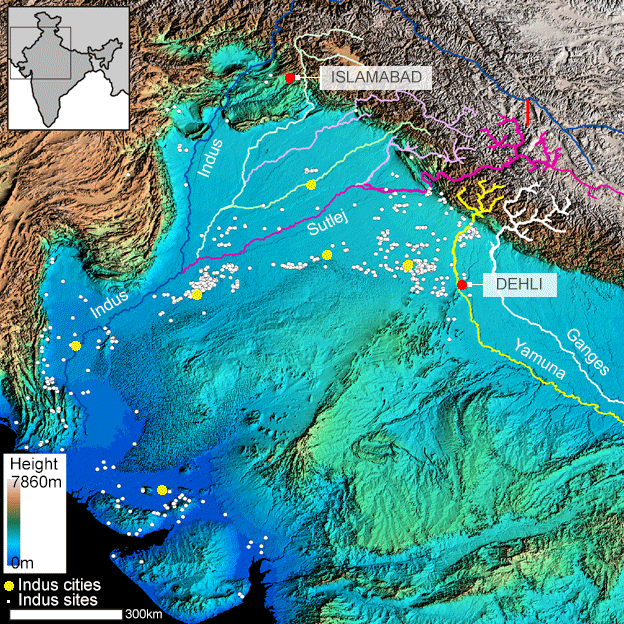

Much of the archaeology of Indus cities, such as Kalibangan and Banawali, is scattered along this old river course.

The team shows the relict valley to be the former trace of today's big Sutlej River, which must have abruptly changed course - as many Himalayan rivers are prone to do.

"They tend to switch on 100-year timescales," explained Prof Sanjeev Gupta from Imperial College.

"But because the Sutlej became incised in its new course, it never switched back and that left the paleo-channel protected. That allowed, I believe, the Indus communities to flourish because they were saved from devastating floods.

"Some of their sites were actually built in the palaeo-channel itself and that makes no sense if there was a big raging Himalayan river there at the time because these people would have been wiped out."

Broken pieces of Indus pottery exposed at the surface at Kalibangan

Dating of the sediments in the palaeo-channel was done using a technique known as optically stimulated luminescence.

It reveals that the initial abandonment of the valley by the Sutlej River commenced after about 15,000 years ago, with complete "avulsion" to its present course shortly after 8,000 years ago.

Prof Gupta said the Indus people were competent engineers and so would have been able to manage their water needs, potentially even accessing underground supplies. But precisely how they operated in these circumstances of reduced water possibilities was now really a question for the archaeologists to answer, he added.

"What is clear though is that this culture had a diverse landscape and they were able to adapt to it," he told BBC News.

Prof Rita Wright is an anthropologist at New York University and unconnected to the new research.

She said it represented a "major building block" in our understanding but stressed also that it concerned just a part of the region occupied by Harappan society.

"It is focused primarily on a single area in northwest India, [but] enormously important.

"In contrast to the Indus Valley, it presents (and provides evidence for) a very different water ecology. No denying that water was one of the major resources in the Indus, so here we have evidence for significant differences between the Indus valley alluvial plain and the Ghaggar monsoon-driven water system."

Indus civilisation urban settlements were spread across what is now NW India and Pakistan

The Harappan site at Mohenjo-daro, Pakistan. It was built on the banks of the Indus River

Prof Gupta has written a longer account of the research which can be read here, external.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external