Rocket rumbles give volcanic insights

- Published

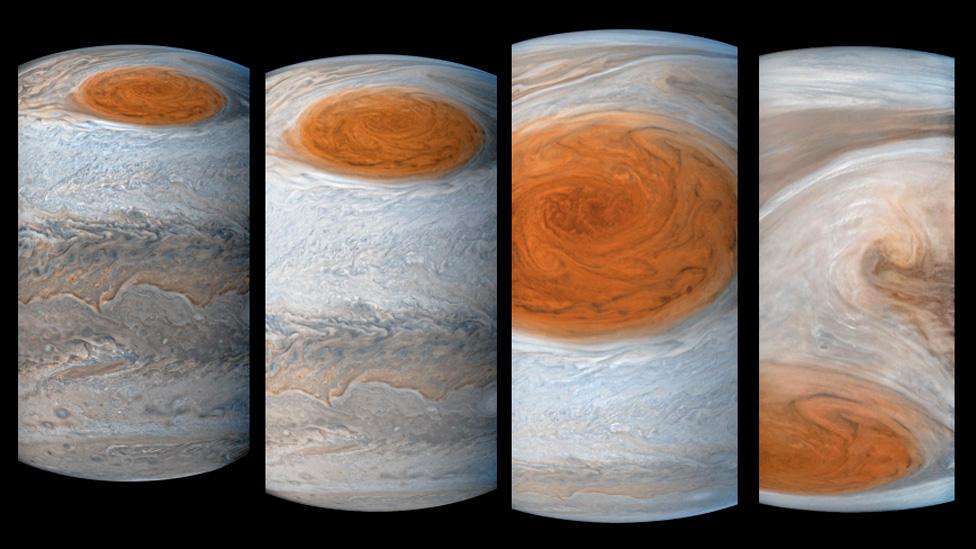

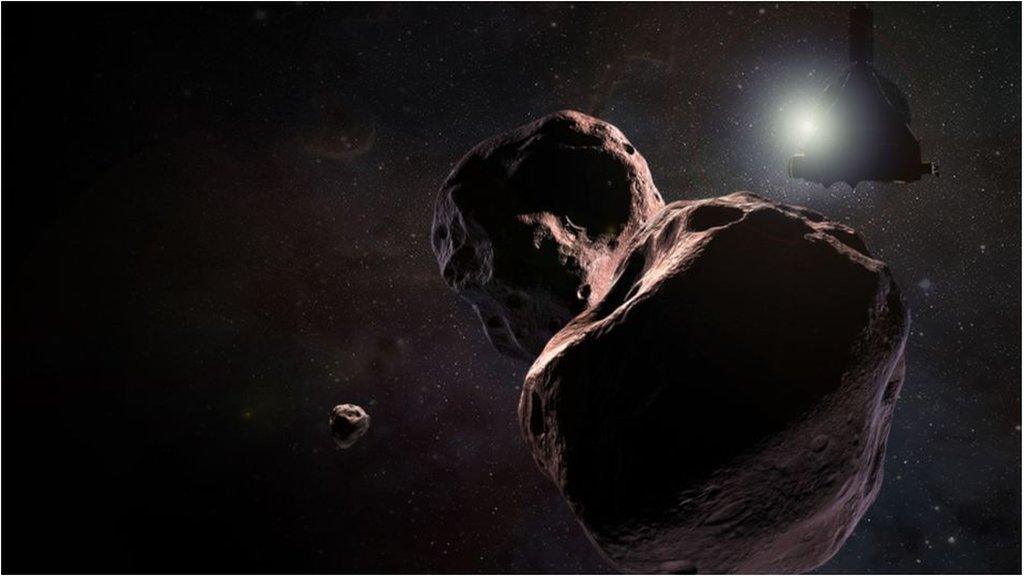

An "upside down volcano" (L) and an "upside down rocket" (R)

What do volcanoes and rockets have in common?

"Volcanoes have a nozzle aimed at the sky, and rockets have a nozzle aimed at the ground," explains Steve McNutt, a geosciences professor at the University of South Florida in Tampa.

It explains why he and colleague Dr Glenn Thompson have installed the tools normally used to study eruptions at the famous Kennedy Space Center.

Comparing the different types of rumblings could yield new insights.

In the case of rockets, the team thinks their seismometers and infrasound (low-frequency acoustic waves) detectors might potentially be used by the space companies as a different type of diagnostic tool, to better understand the performance of their vehicles; or perhaps as a way to identify missiles in flight.

In the case of volcanoes, the idea is to take the lessons learned at Kennedy and fine-tune the algorithms used to interpret what is happening in an eruption.

It might even be possible to develop systems that give early warnings of some of the dangerous debris flows associated with volcanoes.

Glenn Thompson and Steve McNutt: "Kennedy has strong signals to test equipment "

"It all started really as a way to test and calibrate our equipment," says Glenn.

"We don't have any volcanoes in South Florida - obviously. But Kennedy provided some strong sources, and it also gave our students the opportunity to learn how to deploy stations and work with the data."

The team has now recorded the seismic and acoustic signals emanating from about a dozen rockets.

Most have been associated with launches; a few have been related to what are called static fire tests, in which the engines on a clamped vehicle are briefly ignited to check they are flight-ready.

But perhaps the most fascinating event captured so far was the SpaceX pad explosion in September 2016.

This saw a Falcon 9 rocket suffer a catastrophic failure as it was being fuelled.

Many people will have seen the video of the spectacular fireball. But Glenn's and Steve's equipment caught information not apparent in that film, external.

The moment the SpaceX rocket exploded

For example, they detected more than 150 separate sub-events in the infrasound over the course of 26 minutes.

These were likely individual tanks, pipes or other components bursting into flames.

Of course, the SpaceX explosion was an unusual occurrence, and it is the more routine activity that most interests the team. And some clear patterns are starting to emerge in their study of "upside down volcanoes".

"As the rocket gets higher and higher and accelerates, we see a decrease in the frequency in the infrasound - that's basically a Doppler shift because the source is moving away from us," says Steve.

"And then you get a coupling of the signal in the air into the ground and this produces seismic waves recorded on the seismometer.

"So, we get some common features between the infrasound and the seismometer, but then there's a little separation of the energy between the two."

A deadly pyroclastic flow heads down the flanks of the Soufrière Hills volcano in Montserrat

There is a lot still to learn, but the pair think they can distinguish the different types of rockets - to tell a Falcon from an Atlas from a Delta.

There are subtle but significant divergences in their spectral signatures, which almost certainly reflect their distinct designs and modes of operation.

Where in particular the rockets could have instruction for volcano monitoring is in describing moving sources.

A rocket is a very well understood physical process. Its properties and parameters - such as the size of the nozzle orifice, the thrust, the trajectory and the distance - are all precisely known.

The related seismic and acoustic signals should therefore serve as templates to help decipher some of the features of eruptions that share similar behaviours.

Good examples of rapid movement in the volcano setting are the big mass surges like pyroclastic flows (descending clouds of hot ash/rock) and lahars (mud/ash avalanches).

An objective of the team is to improve seismometer and infrasound systems' characterisation of these dangerous phenomena.

This could lead to useful alerts being sent to people who live around volcanoes.

"Assuming you can find a few safe places to put your instruments that are reasonably close, you'd get your advance warning," said Steve.

"What you'd be doing then is getting the time and the strength of the signal and then watching it evolve to figure out which direction it's going.

"If you can do that successfully then you can forecast with a couple of minutes in advance things like lahars and pyroclastic flows downstream."

Glenn added: "I worked on [the Caribbean island of] Montserrat during the crisis from 1995 to 2011, and we did have a rudimentary system even then for tracking the pyroclastic density currents coming down the slopes of the volcano.

"It wasn't quite a real-time application, but we hope with this kind of work that we can improve those algorithms and make them more of an automated alarm system."

The equipment at Kennedy has been temporary, but the team is looking for a permanent installation.

Like everyone, Glenn and Steve are particularly looking forward to the launch of SpaceX's Falcon Heavy vehicle in the New Year.

The Heavy should produce nearly 23 meganewtons of thrust at lift-off, more than any rocket in operation today.

It is sure to make for some interesting seismic and infrasound signals.

Glenn Thompson and Steve McNutt detailed their work here at the Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union, external.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published1 September 2016

- Published12 December 2017

- Published12 December 2017