Alaskan infant's DNA tells story of 'first Americans'

- Published

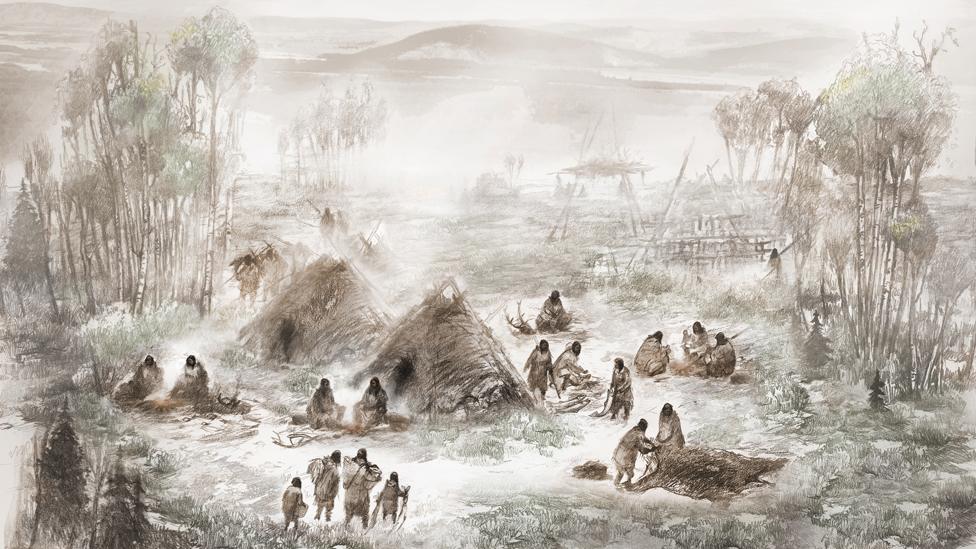

Excavations at the Upward Sun River archaeological site in Alaska

The 11,500-year-old remains of an infant girl from Alaska have shed new light on the peopling of the Americas.

Genetic analysis of the child, allied to other data, indicates she belonged to a previously unknown, ancient group.

Scientists say what they have learnt from her DNA strongly supports the idea that a single wave of migrants moved into the continent from Siberia just over 20,000 years ago.

Lower sea-levels back then would have created dry land in the Bering Strait.

It would have submerged again only as northern ice sheets melted and retreated.

The pioneering settlers became the ancestors of all today's Native Americans, say Prof Eske Willerslev and colleagues. His team has published its genetics assessment in the journal Nature.

An illustration of how the Ancient Beringians at Upward Sun River might have lived

The skeleton of the six-week-old infant was unearthed at the Upward Sun River archaeological site in 2013.

The local indigenous community have named her "Xach'itee'aanenh t'eede gay", or "sunrise girl-child".

The science team refers to her simply as USR1.

"These are the oldest human remains ever found in Alaska, but what is particularly interesting here is that this individual belonged to a population of humans that we have never seen before," explained Prof Willerslev, who is affiliated to the universities of Copenhagen and Cambridge.

"It's a population that is most closely related to modern Native Americans but is still distantly related to them. So, you can say she comes from the earliest, or most original, Native American group - the first Native American group that diversified.

"And that means she can tell us about the ancestors of all Native Americans," he told BBC News.

Scientists study the history of ancient populations by analysing the mutations, or small errors, that accumulate in DNA down through the generations.

These patterns, when combined with demographic modelling, make it possible to draw connections between different groups of people over time.

During the height of the last ice age, lower sea-levels would have opened a land bridge

The new study points to the existence of an ancestral population that started to become distinct genetically from East Asians around 34,000 years ago, and which had completed the separation by roughly 25,000 years ago.

This separation is indicative of the Bering land bridge connecting Siberia and Alaska having been crossed, or, at the very least, of the ancestral population having become geographically isolated in north-east Siberia.

The analysis further suggests that a group of Ancient Beringians, represented by USR1, then subsequently began to diverge from the pioneer migrants. This genetic separation occurs at about 20,000 years ago and is the result of these people staying put in Alaska for several thousand years.

Others in the pioneer wave, however, moved south to occupy territories beyond the ice.

This onward-moving branch ultimately became the two genetic groups that are recognised as the ancestors of today's indigenous populations.

Prof Willerslev said: "Before this girl's genome, we only had more recent Native Americans and ancient Siberians to try to work out the relationships and times of divergence. But now we have an individual from a population between the two; and that really opens the door to address these fundamental questions."

More definitive answers would only come with the discovery of further remains in north-east Siberia and Alaska, the scientist added.

That is complicated in the case of the north-west American state because its acidic soils are unfavourable to the preservation of skeletons and in particular their DNA material.