How to escape from a lion or cheetah - the science

- Published

Scientists say in the final stages of the hunt, it isn't about "high speed"

The antelope can never out-run the cheetah, but it can survive the chase if it twists and turns sharply at the last minute.

That's the finding of a study that tracks the dance of death between the fastest land animal and its prey.

Researchers have been analysing how zebra and antelope escape from lions and cheetahs on the African savannah.

They say hunting at lower speed favours prey, as it offers them the best chance of out-manoeuvring the predator.

"In the final stages of a hunt, it isn't about high speed," said Alan Wilson of the Royal Veterinary College, University of London, UK.

"If the prey tries to run away at speed, it is a very bad move because the predator is faster and can accelerate more quickly, so that plays into the predator's hands.

"The optimum tactics of the prey is to run relatively slowly and turn very sharply at the last moment."

Defining the chase

To determine how wild animals are able to compete for survival on the savannah, scientists compared the athletic abilities of lions and cheetahs with that of their favourite prey - zebra and impala (a type of antelope).

In a study featured in Thursday's episode of the BBC One documentary Big Cats, researchers used specially designed radio collars to track the animals' top speeds, their acceleration and deceleration, and how quickly each animal could turn.

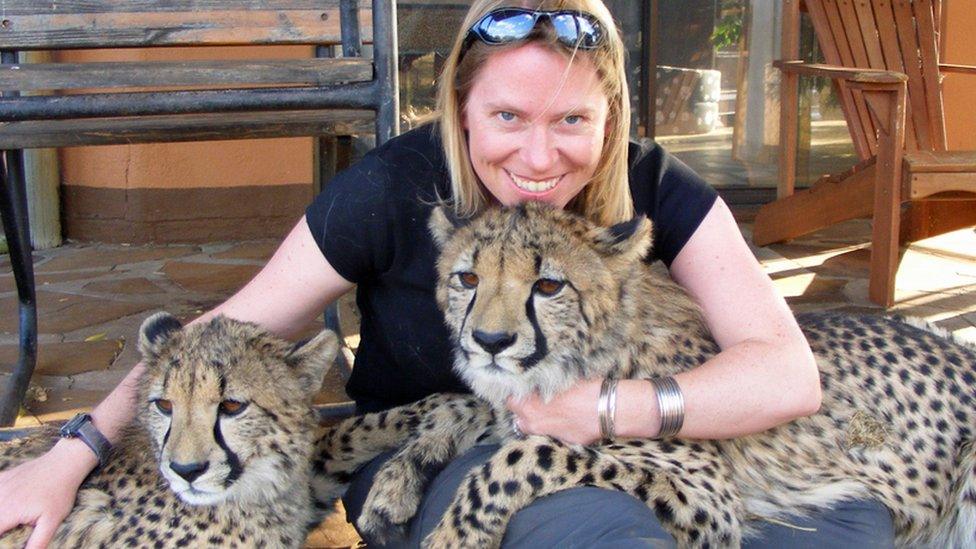

Prof Alan Wilson in Namibia with cheetahs

Seven zebra were fitted with radio collars

They also took a small muscle sample to analyse the animals' maximum muscle power.

The predators turned out to be significantly faster and more powerful than their prey.

However, at lower speeds they were unable to match the zebra and impala for manoeuvrability, allowing these animals a chance of escape.

The study, carried out in collaboration with the University of Botswana, sheds light on the extremes of performance in wild animals and the factors that influence their survival.

"Prey can define the chase," said Prof Wilson. "It decides when to turn, how fast to run. So, it's always one stride ahead of the predator."

Because the prey defines the tactics of the hunt, the predator needs to be more athletic to compete, he added.

The work by the Royal Veterinary College on cheetah locomotion will be shown in Thursday's episode of BBC One's Big Cats documentary.

A cheetah's claws are semi-retractable which gives them good grip for running

The cheetah is known for its impressive running speed of more than 100km/h (60mph). Lions are more powerful than cheetahs, but not as fast on their feet.

Both cheetahs and lions have about 20% more powerful muscles, 37% greater acceleration and 72% greater deceleration capacity than their prey. The cats are successful in about a third of hunts, using a combination of stealth and speed.

Modelling work shows that zebra and impala have the best chance of evading capture if they turn quickly, particularly after slowing very rapidly.

'Evolutionary arms race'

Meanwhile, cheetahs and lions have the highest chance of success if they are travelling only slightly faster than their prey.

Scientists say this reflects the "evolutionary arms race" between predator and prey.

Put simply, if predators were too successful at catching their prey, they would run out of food to eat.

The research is published in the journal Nature, external.

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.

- Published27 June 2017

- Published26 December 2016