Ancient Britons 'replaced' by newcomers

- Published

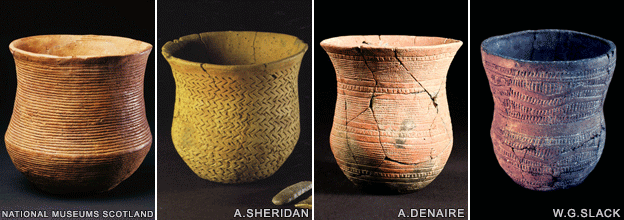

Beaker pottery starts to appear in Britain around 4,500 years ago

The ancient population of Britain was almost completely replaced by newcomers about 4,500 years ago, a study shows.

The findings mean modern Britons trace just a small fraction of their ancestry to the people who built Stonehenge.

The astonishing result comes from analysis of DNA extracted from 400 ancient remains across Europe.

The mammoth study, published in Nature,, external suggests the newcomers, known as Beaker people, replaced 90% of the British gene pool in a few hundred years.

Lead author Prof David Reich, from Harvard Medical School in Cambridge, US, said: "The magnitude and suddenness of the population replacement is highly unexpected."

The reasons remain unclear, but climate change, disease and ecological disaster could all have played a role.

People in Britain lived by hunting and gathering until agriculture was introduced from continental Europe about 6,000 years ago. These Neolithic farmers, who traced their origins to Anatolia (modern Turkey) built giant stone (or "megalithic") structures such as Stonehenge in Wiltshire, huge Earth mounds and sophisticated settlements such as Skara Brae in the Orkneys.

But towards the end of the Neolithic, about 4,450 years ago, a new way of life spread to Britain from Europe. People began burying their dead with stylised bell-shaped pots, copper daggers, arrowheads, stone wrist guards and distinctive perforated buttons.

Co-author Dr Carles Lalueza-Fox, from the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE) in Barcelona, Spain, said the Beaker traditions probably started "as a kind of fashion" in Iberia after 5,000 years ago.

From here, the culture spread very fast by word of mouth to Central Europe. After it was adopted by people in Central Europe, it exploded in every direction - but through the movement of people.

Monument builders

Prof Reich told BBC News: "Archaeologists ever since the Second World War have been very sceptical about proposals of large-scale movements of people in prehistory. But what the genetics are showing - with the clearest example now in Britain at Beaker times - is that these large-scale migrations occurred, even after the spread of agriculture."

The genetic data, from more than 150 ancient British genomes, reveals that the Beakers were a distinct population from the Neolithic British. After their arrival on the island, Beaker genes appear to swamp those of the native farmers.

Prof Reich added: "The previous inhabitants had just put up the big stones at Stonehenge, which became a national place of pilgrimage as reflected by goods brought from the far corners of Britain."

He added: "The sophisticated ancient peoples who built that monument and ones like it could not have known that within a short period of time their descendants would be gone and their lands overrun."

The newcomers brought ancestry from nomadic groups originating on the Pontic Steppe, a grassland region extending from Ukraine to Kazakhstan. These nomads moved west during the Neolithic, mixing heavily with established populations in Europe. The Beaker migration marks the first time this eastern genetic signature appears in Britain.

Archaeologist and study co-author Mike Parker Pearson, from University College London (UCL), said Neolithic Britons and Beaker groups organised their societies in very different ways. The construction of massive stone monuments, co-opting hundreds of people, was an alien concept to Beakers, but the Neolithic British community "has that absolutely as its core rationale".

"[The Beaker people] are not prepared to collaborate on enormous labour-mobilising projects; their society is more de-centralised," said Prof Parker Pearson. "We don't have a good expression for it, but the Americans do, and that is: nobody is willing to work for 'The Man'."

'Neolithic Brexit'

The Beaker folk seemed to favour more modest round "barrows", or earth burial mounds, to cover the distinguished dead. The group is also intimately associated with the arrival of metalworking to Britain.

Prof Parker Pearson commented: "They're the people who bring Britain out of the Stone Age. Up until then, the people of Britain had cut themselves off from the continent - 'Neolithic Brexit'. This is the moment when Britain re-joins the continent after 1,000 years of isolation - most of the rest of Europe was well out of the Stone Age by this point."

What triggered the massive genetic shift remains unclear. But a paper published in PNAS journal last year, external suggested a downturn in the climate around 5,500 years ago (3,500 BC) pushed Neolithic populations into a thousand-year-long decline.

Neolithic people built sophisticated settlements at Skara Brae in Scotland

Dr Steven Shennan, from UCL, who co-authored that study, told BBC News: "In Britain, after a population peak at around 3,500 or 3,600 BC, the population goes down steadily and it stays at a pretty low level until about 2,500 BC and then starts going up again. Around 2,500 BC the population is very low and that's precisely when the Beaker population seems to come in."

The reasons behind this slow population decline were probably complex, but the temporary downturn in the climate caused a permanent change in the way people farmed. One possibility is that the over-exploitation of land by Neolithic farmers applied pressure to food production.

Plague question

But disease may also have played a role in the population shift: "We have some intriguing evidence that some of the Steppe nomads carried plague with them," said Lalueza-Fox.

"It could just be that the plague went with these migrants into Britain and the Neolithic population had not been in contact with this pathogen before."

Whatever did happen, Prof Parker Pearson is doubtful about the possibility of a violent invasion. The Beakers, he said, were "moving in very small groups or individually".

He explained: "This is no great horde, jumping in boats en masse... it's a very long, slow process of migration." Furthermore, the incidence of interpersonal violence appears to be higher in Neolithic Britain (7%) than it was in the Beaker period (1%)

The Nature study examines the Beaker phenomenon across Europe using DNA from hundreds more samples, including remains from Holland, Spain, the Czech Republic, Italy and France.

Another intriguing possibility links the Beaker people with the spread of Celtic languages.

Prof Reich commented: "It's very exciting to think that maybe Celtic languages could have been spread by the Beaker phenomenon through Central Europe and into Britain, but that's not the only scenario."

Indeed, many archaeologists and linguists believe Celtic spread thousands of years later. But Dr Lalueza-Fox said: "In my view, the massive population turnover must be accompanied by a language replacement."

Follow Paul on Twitter., external