Tasmanian tiger 'joeys' revealed in 3D

- Published

It is a fascinating insight into the biology of an extinct animal.

Scientists have scanned all known preserved Tasmanian tiger "joeys" to better understand the marsupial's key early development phases.

The study, external tracks the changes to the infants' skeleton and internal organs as they grew inside the mother's pouch.

It captures in detail the transition the tiger joey made from something that resembled all other marsupials to something that looked more dog-like.

"We were surprised; they took on the puppy-dog look really quite late in pouch life - towards the end of the three months," explained Dr Andrew Pask from the University of Melbourne, Australia.

"So, when they're first born they have these really well developed forearms to be able to crawl from their mother's urogenital sinus up to the pouch, and a really well developed jaw to be able to latch on to the teat. That's quite different to us, or a mouse, say.

"It's only really late on that they grow the extended hind limbs to give them that dog appearance," he told BBC News.

CT scanning's great plus is that it is a non-destructive technique

The Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus) was so-called because of its striped lower back.

The marsupial once ranged throughout Australia and New Guinea but was driven to extinction as a result of hunting and competition from both humans and dingoes, the Australian wild dogs.

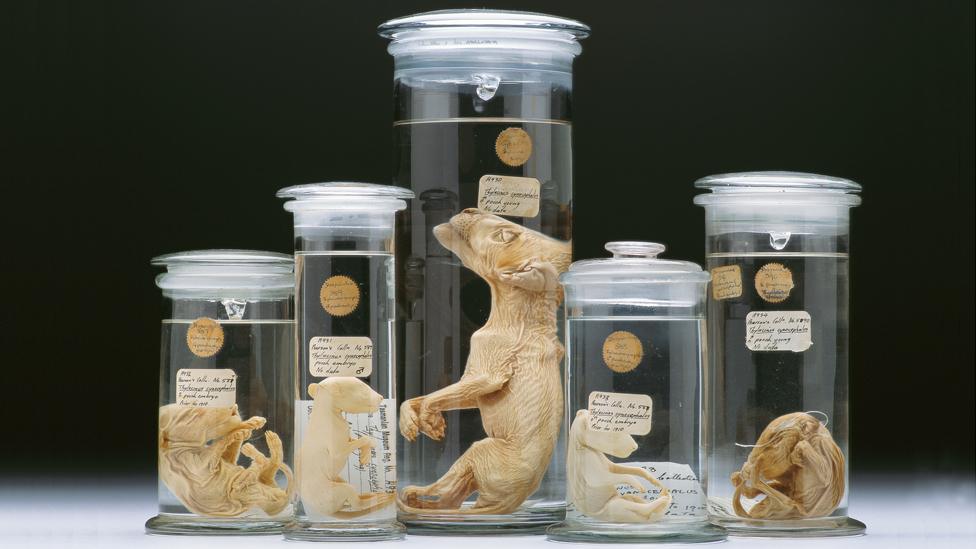

Its last known living individual died in captivity in Hobart Zoo in 1936. But there remain preserved specimens in collections and in particular 13 ethanol-preserved joeys.

The Tasmanian tiger was so-called because of its stripes

The specimens cover ages from two to 12 weeks. The white scalebar is 10mm

The Melbourne team scanned all 13, including four that were held in Prague in the Czech Republic.

The technique of X-ray Computed Tomography (CT) allowed the scientists to virtually dissect the joeys, and subsequently to build 3D models - and even to print copies of those models.

"Until now, there have only been limited details on [thylacine] growth and development. For the very first time we have been able to look inside these remarkably rare and precious specimens," said Axel Newton, a PhD student and lead author on the Royal Society paper describing the investigation.

A joey would live in its mother's pouch for about 12 weeks

The scientists want to learn how the marsupial evolved to look so similar to a dog, given that their last common ancestor lived about 160 million years ago.

It is a classic example of convergence where evolution arrives at the same solutions in the traits of animals having come to them from very different directions.

The new scans and earlier genetics work will hopefully now lead the team to some firm conclusions.

"We sequenced the genome of the thylacine just before Christmas, and we're really asking that question now: can you see the same genes doing the same things to give you the same body form?" said Dr Pask.

"We really don't understand how evolution works at the DNA level. And so looking at the thylacine and studying its development may give us some insights into that," he told BBC News.

Details of the team's study is published in the journal Open Science, external.

A mother and three young thylacines pictured around 1910 in Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external