Shipping faces demands to cut CO2

- Published

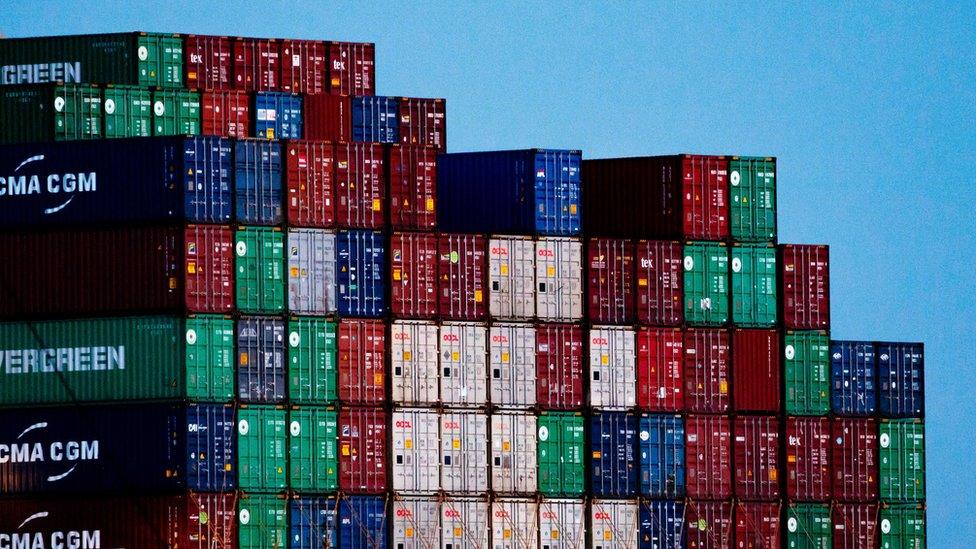

A battle is under way to force the global shipping industry to play its part in tackling climate change.

A meeting of the International Maritime Organisation in London next week will face demands for shipping to radically reduce its CO2 emissions.

If shipping doesn't clean up, it could contribute almost a fifth of the global total of CO2 by 2050.

A group of nations led by Brazil, Saudi Arabia, India, Panama and Argentina is resisting CO2 targets for shipping.

Their submission to the meeting says capping ships' overall emissions would restrict world trade. It might also force goods on to less efficient forms of transport.

This argument is dismissed by other countries which believe shipping could actually benefit from a shift towards cleaner technology.

The UK's Shipping Minister Nusrat Ghani told BBC News: "As other sectors take action on climate change, international shipping could be left behind.

"We are urging other members of the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) to help set an ambitious strategy to cut emissions from ships."

Trade and prosperity

The UK is supported by other European nations in a proposal to shrink shipping emissions by 70%-100% of their 2008 levels by 2050.

Guy Platten from the UK Chamber of Shipping said: "We call on the global shipping industry to get behind these proposals - not just because it is in their interests to do so, but because it is the right thing to do.

"The public expects us all to take action, they understand that international trade brings prosperity, but they rightly demand it is conducted in a sustainable and environmentally friendly way. We must listen to those demands, and the time for action is now."

The problem has developed over many years. As the shipping industry is international, it evades the carbon-cutting influence of the annual UN talks on climate change, which are conducted on a national basis.

Instead the decisions have been left to the IMO, a body recently criticised for its lack of accountability and transparency.

The IMO did agree a design standard in 2011 ensuring that new ships should be 30% more efficient by 2025. But there is no rule to reduce emissions from the existing fleet.

The Clean Shipping Coalition, a green group focusing on ships, said shipping should conform to agreement made in Paris to stabilise the global temperature increase as close as possible to 1.5C.

Tangible goals

A spokesman said: "The Paris temperature goals are absolute objectives. They are not conditional on whether the global economy thinks they are achievable or not."

So the pressure is on the IMO to produce an ambitious policy. The EU has threatened that if the IMO doesn't move far enough, the EU will take over regulating European shipping. That would see the IMO stripped of some of its authority.

A spokesman for the Panamanian government told BBC News his nation supports the Paris Agreement.

"But", he said, "Panama, as a developing country that depends on the maritime sector for its progress, and aware that the welfare of its population relies on shipping, believes in the necessity of a well though-out and studied strategy that allows sustainable and efficient reduction of emissions.

"To haste into an uncalculated strategy that aims to reduce emissions to zero by the year 2050 does not take into account the current state of technology."

A recent report from the International Transport Forum at the rich nations' think tank the OECD said maximum deployment of currently known technologies could achieve almost complete decarbonisation of maritime shipping by 2035., external

A spokesperson for another of the nations resisting targets told BBC News: "My country pushed very hard to get the deal in Paris. But you will notice that many of the countries opposing the restrictions on CO2 are developing countries that are distant from some of their markets."

Campaigners say huge improvements in CO2 emissions from existing ships can be easily be made by obliging them to travel more slowly. They say a carbon pricing system is needed.

International shipping produces about 1,000 million tonnes of CO2 annually - that's more than the entire German economy.

The meeting runs from Tuesday.

Follow Roger on Twitter., external