Iron Age study targets British DNA mystery

- Published

This gold torc from Staffordshire was crafted at some point between 400 and 250 BC

A project to sequence DNA from about 1,000 ancient remains could resolve a genetic mystery involving people from south-east Britain.

A recent study showed that the present-day genetic landscape of Britain was largely laid down by the Bronze Age.

But Prof David Reich told the BBC that this wasn't the end of the story.

During the Iron Age or Roman Period, the DNA of people in the south-east diverged somewhat from that of populations in the rest of the Britain.

Prof Reich, from Harvard Medical School in Boston, told BBC News: "We are initiating an effort to follow up on this observation - and more generally to provide a fine-grained picture of population structure of Iron Age and Roman Britain - using a study that will be on a scale of 1,000 newly reported British samples."

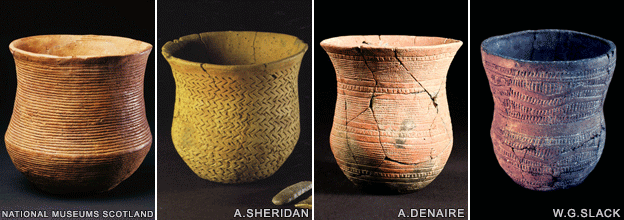

The migration of "Beaker people" - named after their characteristic pots - transformed the genetic make-up of Britain in the late Neolithic

This, he explained, "would be far larger than any previously reported dataset".

For comparison, the total global data-set of DNA sequences from ancient human remains currently stands at about 1,400 individuals.

The migration of people associated with the Beaker culture from continental Europe into Britain at the end of the Neolithic period (around 4,000 years ago) remains the most significant event to shape the genetics of subsequent populations on the island.

The Beakers are intimately associated with the introduction of metal-working to Britain. They largely replaced the existing population of farmers who had built Stonehenge and other impressive monuments around the country.

The Stonehenge builders were largely replaced by the Beaker people, but pockets may have lingered

But at some point after the Bronze Age, groups in the south-east appear to have mixed with a population similar to those Stonehenge builders who inhabited Britain before the Beakers arrived.

Most people from south-east Britain still trace most of their ancestry to the Beaker people, but the later mixing event had a bigger impact than Medieval Anglo-Saxon migrations - traditionally seen as the foundation point of English history.

Prof Reich said his team currently had three working hypotheses to explain the result. While the Beakers replaced around 90% of the ancestry in Britain, it's possible that a pocket (or pockets) of Neolithic farmers held out in isolation somewhere for hundreds of years.

During the Iron Age (which began around 3,000 years ago), they mixed back in with the general population, diluting the Beakers' genetic background with a type of ancestry that's now stronger around the Mediterranean than in Northern or Central Europe.

Alternatively, the genetic data may be hinting at a separate migration from continental Europe during the Iron Age - perhaps one that brought Celtic languages into Britain.

The third possibility is that scholars have simply underestimated the genetic impact of the Roman occupation, which lasted in Britain from AD 43 until 410. Roman settlers from the Italian peninsula would have traced a large proportion of their ancestry to Neolithic farmers like those that inhabited Britain before the arrival of the Beaker people.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external