Indonesian study into health risks of microplastics

- Published

- comments

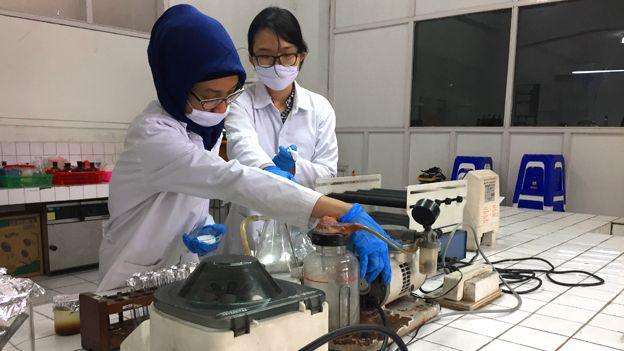

The research is being led from Soegijapranata Catholic University

Indonesian scientists have launched the largest ever study into whether tiny plastic particles can affect human health.

They are investigating the presence of plastic in seafood while also tracking the diets of 2,000 people.

There is no evidence yet that ingesting small pieces of plastic is harmful but potential impacts cannot be ruled out.

Plastic pollution has become so severe in Indonesia that the army has been called in to help.

While public attention is focused on larger items like bags and bottles choking rivers and canals, there is emerging scientific concern over the long-term implications of smaller and less visible pieces known as microplastics.

The project is being undertaken in Semarang, an industrial port city of 1.7 million people, on the north coast of the Indonesian island of Java.

As a coastal city, Semarang is a place where fish consumption is high

Led by food technologist Inneke Hantoro, the aim is understand how much plastic is contained in seafood, how much of it people eat and whether a safe level of consumption can be devised.

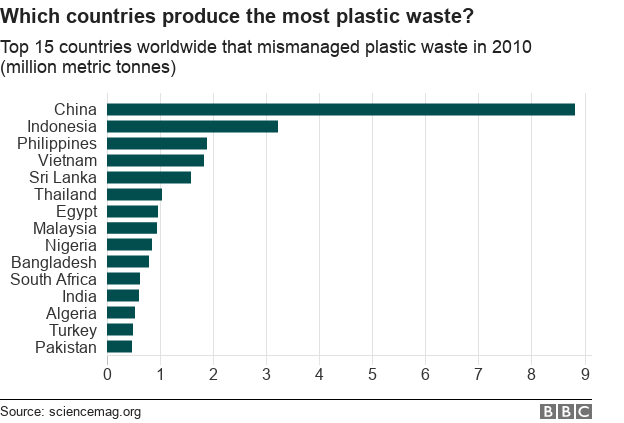

Her initiative is a response to US plastics researcher Jenna Jambeck and colleagues concluding that Indonesia was the world's second largest contributor of plastic waste to the oceans after China.

Ms Hantoro, of Soegijapranata Catholic University, says the lack of evidence about microplastics causing harm is not a reason to delay investigating the risks.

She told BBC News: "With the uncertain conditions right now, where the toxicological data is still limited, we cannot let the situation run as usual because we know consumers are starting to be aware of the presence of plastics – it will make them worry, so we need to do something."

She concedes that until more data is available, it will not be possible to set a definitive safety standard for plastic consumption so she’s hoping to come up with "interim guidance".

"We could propose a food safety standard to remove seafood that contains a very high level of microplastics from the market – people don’t want to buy something that contains plastic," she added.

Microplastics are on the scale of millimetres and smaller

The first stage of the work involved gathering 450 samples of six different types of seafood from local waters and also from further afield, and screening them for microplastics.

I joined her on a visit to fish farms on the coast near Semarang. To reach them we had to travel by boat through mangrove swamps that were blighted by plastic – huge loads of it hung from the branches and lay tangled in the roots.

The research has found that every species tested contained some plastic particles, including fragments and fibres – tilapia were the worst with 85% seen with plastic.

The majority of mullet, shrimp, and milk fish tested also had plastic particles. Cockles had the lowest reading with 52% containing plastic.

The roots of mangroves are a tangled mess of discarded plastic

These findings are broadly in line with similar research conducted in the UK and elsewhere, and they confirm that plastic contamination of seafood is a global problem.

But the next phase of the work in Semarang breaks new ground with an unprecedented campaign to follow the diets of 2,000 volunteers over a period of 2-4 weeks.

As a coastal city, Semarang is known to have a relatively high consumption of seafood and a key task is to find out how people prepare it and whether they take any steps that might minimise their intake of plastic.

Milk fish, for example, can be eaten whole, including their intestines, which may be where microplastics might accumulate.

One of the co-authors of the study is a Dutch environmental scientist, Prof Ad Ragas, of Radboud University.

He plays down any fears of immediate health hazards from microplastics but says the problem does need to be understood.

"Keep in mind that it’s not as if everybody is dying from the plastics problem," he told BBC News.

"We know it's there but we don't know yet whether fish are dying or people are dying because of the microplastics, so there’s no reason or proof to be pessimistic there.

"But we don’t know for sure, so that’s the uncertainty we have to live with."

Harjanto Halim, the boss of Marimas PT, talks about his EcoBricks mission

This comes as the city authorities in Semarang have organised a major clean-up - the main streets and rivers look largely clear of plastic waste.

But because the city only has one official landfill site, at least 200 illegal ones have sprung up in poorer districts and in the outskirts of Semarang.

We saw one sprawling dump on the coast, where thousands of bags of rubbish lay heaped and torn, with plastic waste blown by the wind into the ocean, all of it destined to break down into smaller fragments.

In an effort to minimise the amount of plastic reaching the environment, one major food packaging factory in the city has launched an initiative to contain waste and raise awareness.

PT Miramas, which uses plastic for sachets, bottles and other containers, is sponsoring classes in EcoBricks, a scheme that transforms plastic waste into blocks that can be used as furniture or building materials.

Illegal coastal dumps have sprung up in poorer districts

Harjanto Halim, director of the company, told me that at the moment he could see no alternatives to using plastic so he wanted to teach people how to make use of it and prevent it leaking into the environment.

As we spoke, dozens of people were learning how to prod old plastic bags into drinks bottles. The filled bottles are then being glued together in batches to form large "bricks" which can be stacked on top of each other.

"You cannot make a magical thing happen in a blink of an eye,” said Mr Halim, acknowledging that this project alone will not change attitudes."The people of Indonesia still consider throwing trash into the street or river is normal… but if I am able to get support from the government and schools I think we can make a difference."