Dinosaur parenting: How the 'chickens from hell' nested

- Published

How do you sit on your nest of eggs when you weigh over 1,500kg?

Carefully - according to a new study from an international team of researchers in Asia and North America.

Dinosaur parenting has been difficult to study, due to the relatively small number of fossils, but the incubating behaviour of oviraptorosaurs has now been outlined for the first time.

Scientists believe the largest of these dinosaurs arranged their eggs around a central gap in the nest.

This bore the parent's weight, while allowing them to potentially provide body heat or protection to their developing young, without crushing the delicate eggs.

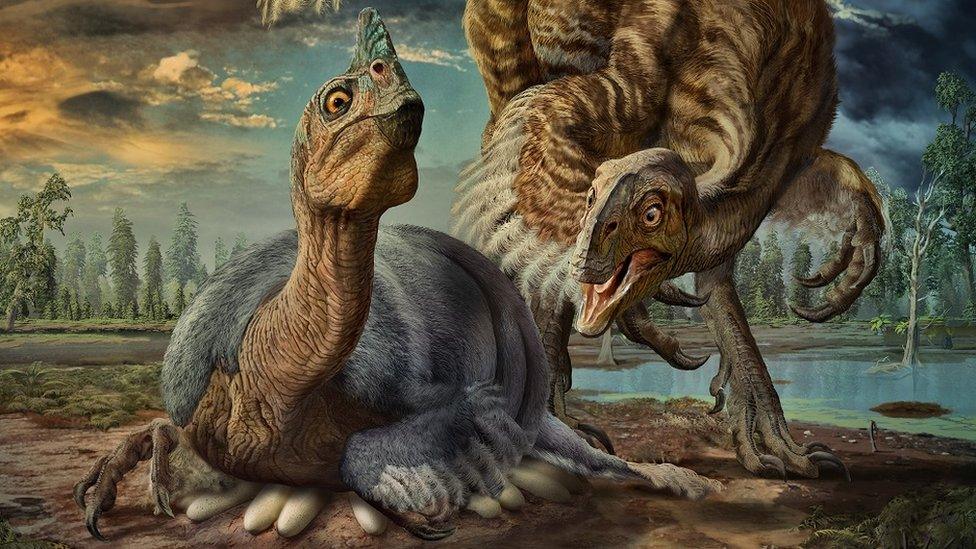

The feathered ancient relatives of modern birds, oviraptorosaurs lived in the Late Cretaceous period, at least 67 million years ago.

Their bony crests and long, lizard-like tails led one species, Anzu wyliei, to be dubbed the "chicken from hell."

A 60cm diameter nest - some of the parent's weight would have rested on the eggs

"It's a really interesting group of dinosaurs," study co-author Darla Zelenitsky from the University of Calgary told BBC News.

"Most of them were of small size so probably 100kg or less. They're very bird-like; they have a very parrot-like skull. While they are relatively rare, there are a number of interesting specimens."

The group looked at the shape and size of over 40 different nests, mostly originating in China and Mongolia, in order to determine incubating behaviour.

They found that clutch diameter ranged from 35cm in smaller species to 330cm in the largest, Macroelongatoolithus.

The central gap in the nest appeared to increase with increasing species size.

The nest of a large oviraptorosaur - there is a large central opening for the parent to sit on

This adaptation is not seen in birds.

"It's pretty much only found, from what we've seen, in this group. They've got these very elongate eggs. So it's pretty much unique to them," observed Dr Zelenitsky.

Some studies, external have suggested that these elongate eggs were likely blue-green in colour. The largest ones have the most delicate shells, but can weigh over 6kg.

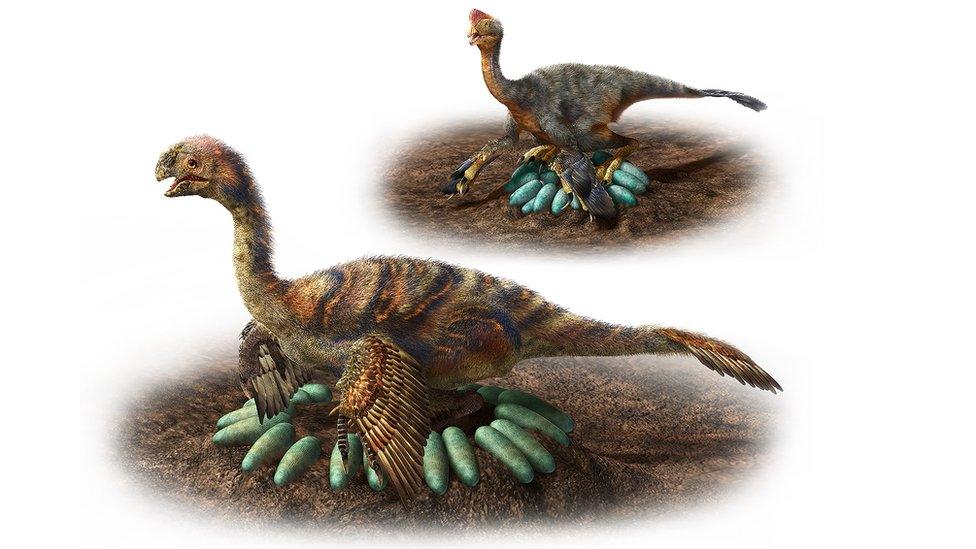

Scientists concluded that the smaller varieties of oviraptorosaur likely sat directly on their clutch of eggs, which would have been layered on top of each other.

The nests of larger species showed a single ring of eggs arranged around a large central gap of earth, which would have supported most of the parent dinosaur's weight.

Illustration: nesting behaviours of large and small oviraptorosaurs

Commenting on the study, Dr Lindsay Zanno from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences described it as "simple, yet elegant."

"Dinosaur nests are particularly valuable because they give us insight into how dinosaurs evolved... adopting behaviours that allow them to warm or protect their eggs without squashing them with their behemoth bodies."