Trump election shortens US Thanksgiving family dinners

- Published

President Trump was elected after a tight and divisive race

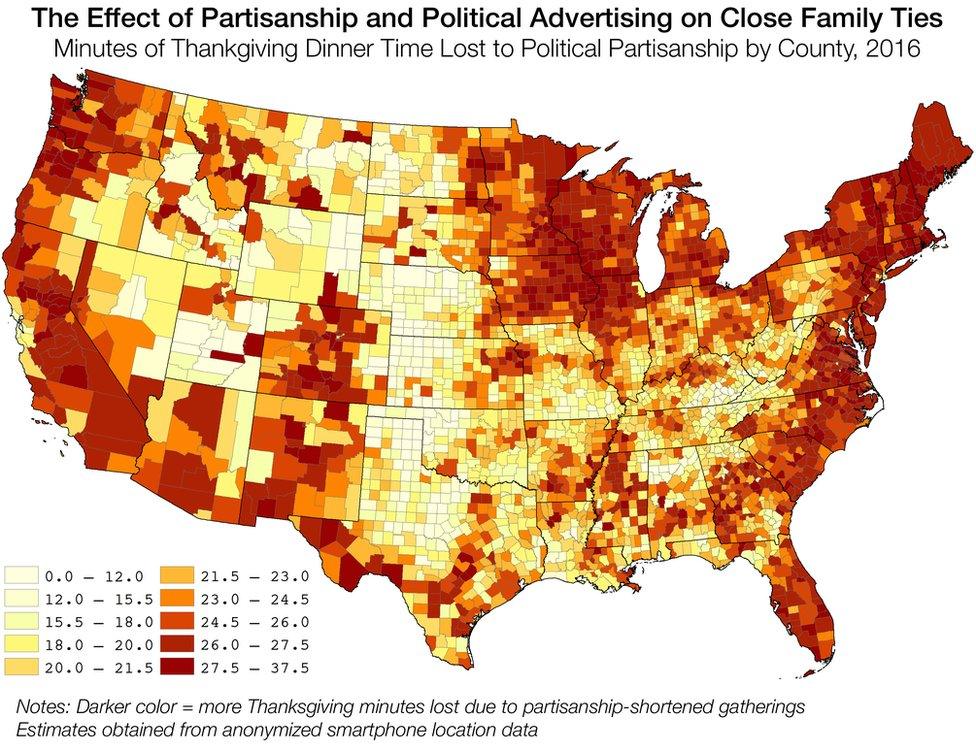

Researchers say that Thanksgiving visits to family members in 2016 were significantly shorter due to greater political polarisation after President Trump's election.

Anonymous cell phone data on 10 million users was combined with voting records to establish voter movements.

The team found that electors cut the time spent with political opponents by up 30-50 minutes compared to 2015.

Voters exposed to widespread political TV ads spent even less time on visits.

The traditional US Thanksgiving holiday visit and dinner is one of the more widely observed rituals in American life, drawing together young and old family members often from distant locations.

However Thanksgiving dinners can also be awkward especially with greater political polarisation in the US in recent years.

The authors were inspired to carry out this study after suffering "uncomfortable and politically divisive" Thanksgiving dinners themselves in 2016 and having had many anecdotal accounts of similar experiences.

Rather than carry out a survey where people might fail to recall the exact times of their Thanksgiving visits, the researchers decided to trust in anonymous cell phone location data of 10 million users merged with precinct level voting records.

When this method was used to model the actual national result of the election it was found to be highly accurate, predicting a share of 0.516 for Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton, which was very close to the vote share she received of 0.511.

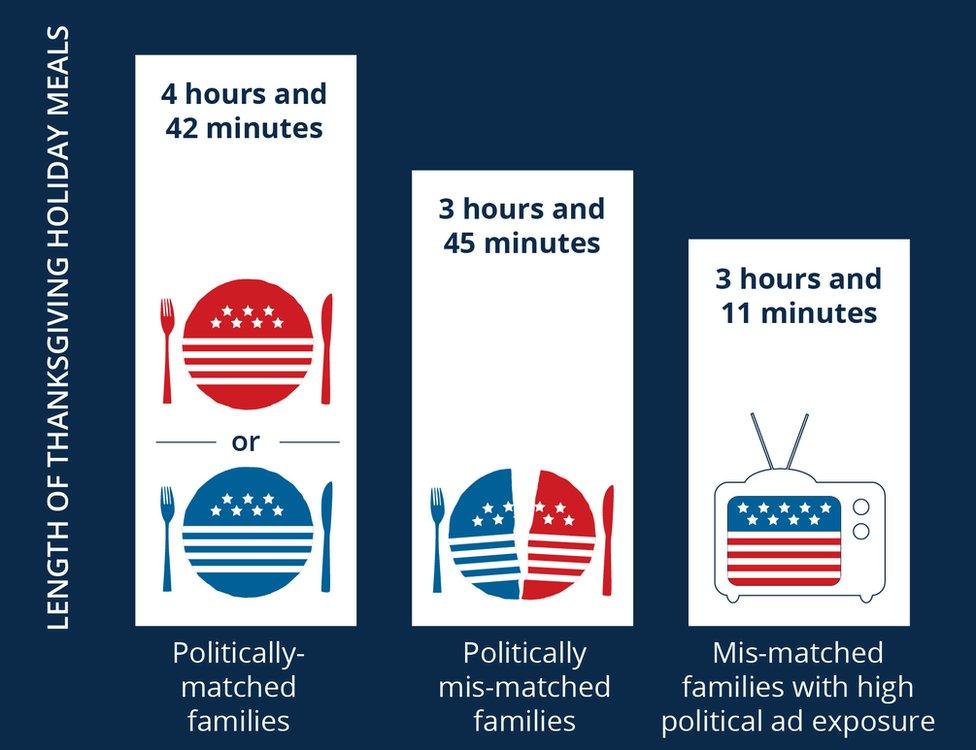

To test the length of the Thanksgiving visits, each of the voters was given a weighting depending on how their home area had voted. When these phone users visited areas that had voted differently from them for the family get-together, the researchers found that the visits lasted 30-50 minutes less than the average visit of 4.2 hours in 2015, when there was no election.

Republican voters visiting Democratic family members cut their encounters by 50-70 minutes while Democrats cut their visits by 20-40 minutes.

"We focussed on Thanksgiving, which is this fascinating natural experiment where many people travel great distances and you get this great experiment in political mingling," author Prof Keith Chen from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), told BBC News.

"In San Francisco, you saw zero time lost, because basically you can't find a Republican to eat with, but in Santa Monica, near Los Angeles, a lot of residents eat with people from Orange County - one of the most conservative areas in the US - so it's interesting that you see people travel actual distances and great political distances over the Thanksgiving break."

The researchers also looked at data from voters travelling from regions where people were exposed to large amounts of political advertising. These voters spent even less time with their relatives.

"If you lived in Florida, in Orlando for example you got more than 20,000 political ads over the election season, so it's a big treatment," said Prof Chen.

"What we see is that the Thanksgiving dinner shortening is three times higher in these areas than ones that didn't - so we looked at those areas in 2015, when there wasn't an election and before the drug of political advertising was administered, so that really nailed if for us as a political effect."

The study says that overall, an estimated 33.9 million person-hours of cross-partisan discussion and debate were eliminated in 2016.

The authors speculate that this creates a feedback mechanism by which partisan segregation further reduces opportunities for close cross-party conversations.

They say that families spending less time together at thanksgiving is a symptom of "decline in social capital", by which they mean the way in which values like trust and co-operation are eroded as people participate less in civic activities.

"Some people don't see losing dinner with relatives as a particularly large cost," said co-author Ryne Rohla, from Washington State University.

"I've talked to people who are, 'well, so what?' Personally I think it is concerning. To me it's a symptom of a broader decline in the social fabric of the United States."

The study has been published, external in the journal Science.