Could an emoji save your life?

- Published

Emoji might not be your first line of communication in a disaster...

But researchers feel they could make a difference during emergencies like earthquakes, where every second counts.

Now, an international group of scientists are lobbying for an earthquake emoji to be added to the Unicode set - the standard group of icons available on digital devices worldwide.

But can one emoji really make a difference in a crisis?

Emoji-quake

"Maybe up to one third of the world's population might be exposed to some [seismological] hazard," explains University of Southampton seismologist Dr Stephen Hicks, a founder of the Emoji-quake campaign, external.

"So we really want to be able to communicate to all of those regions, all of those different languages, and an emoji is an amazing way of doing that."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The campaign aims to find an earthquake-appropriate design to be submitted to Unicode.

Dr Sara McBride, a social scientist with the United States Geological Survey, is also part of the effort.

"Emoji can cross the boundaries of written language, helping communicate valuable information to people who may struggle to read a certain language... [they] help us communicate this complex threat faster to more people," she told BBC News.

Why earthquakes?

"The problem with an earthquake," says Dr Hicks, "is it's a very complex process; it's sort of hidden. It's not as tangible as a volcano or a tornado."

Unlike many other weather and climate related events, where longer warning times or visible signs are available, earthquakes move incredibly quickly and are difficult to measure while they are still occurring.

Populations in areas like Japan and Mexico are reliant on earthquake early warning technology, which issues an alert on digital devices and broadcast media.

A catfish icon appears with Japan's alerts, echoing the country's earthquake mythology

"You may have seconds to get under a table or to protect yourself," explains Dr Hicks. "That can be life saving in many cases. If you send a text message as part of that alert you don't want too much wording in there."

Being (relatively) young as a language, there aren't any conclusive studies on emoji and response times in emergency situations.

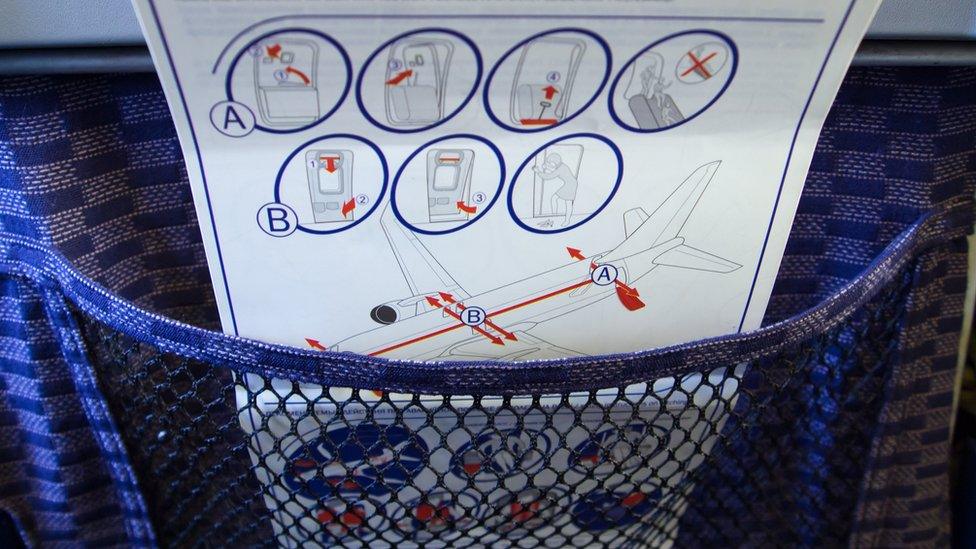

However, pictographs and other visuals have a track record of being faster and easier to understand than written information - which is why the safety card on the back of your aeroplane seat looks the way it does.

"A few studies do suggest that the use of emoji decreases the time it takes to mentally digest information," says Dr McBride. "But... we always want more data."

However, the emoji wouldn't just play a role in warning systems - it might actually help seismologists to work out where and when earthquakes are happening.

Currently, people are most likely to tweet a version of "did I just feel an earthquake?" in their own language.

But with one earthquake emoji being used around the world, it would be the equivalent of having a vast population of seismometers.

"Tweets can be geotagged... we can often then detect the earthquake using social media faster than we can through seismic waves travelling through the Earth. So if we know that an earthquake's happened sooner, then we know how to respond to it and send aid teams in there," Dr Hicks told the BBC.

Could emerji be a thing?

The potential usefulness of emoji in emergencies could extend well beyond earthquakes.

"They're the closest thing we have to a universal language," says Sara Dean, a designer and architect in San Francisco.

"One of the big bottlenecks in using social media as an emergency response tool is language... bridging that gap and reducing that bottleneck is especially important during the first couple of days after an emergency."

Ms Dean and a team of other designers came up with emerji, external - an entire set of emoji dedicated to climate and environmental events.

Unicode are currently considering Emerji's flood and earthquake designs.

"People are already using emoji to talk about emergencies all the time. But because we don't have climate disaster emoji they're piecing them together from other emoji," commented Ms Dean.

Twitter users have combined the fire and tree emoji to share information about California wildfires. But Ms Dean points out that this is problematic as it's difficult to predict what emoji combinations people will choose to use.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

For her, it feels essential that people have a means to share resources across language barriers on social media in a crisis situation.

"These are global issues and we need to be able to have global conversations about them," she told BBC News.

Follow Mary on Twitter, external.