Lost history of brown bears in Britain revealed

- Published

The jaw of a bear from Foxhole Cave, Derbyshire

A new study reveals the hidden history of brown bears in Britain, suggesting they still roamed wild 1,500 years ago.

The research raises two scenarios. Either "native bears" went extinct around the early Middle Ages, or they disappeared some 3,000 years ago in the Bronze Age or in Neolithic times.

Live bears were also imported by the Romans for fighting or displays.

Little is known about the animal's history, despite talk of "re-wilding", says archaeologist Dr Hannah O'Regan.

Her trawl of museum archives and published records is the most detailed examination yet of the brown bear in Britain.

"The brown bear has been very closely associated with people for thousands of years in Britain - either wild or captive," says Dr O'Regan, from the department of classics and archaeology at the University of Nottingham.

"Brown bears and people have been inter-linked through time. We see that today with our teddy bears."

The brown bear was once found across Eurasia and North America

It is not possible to say exactly when and where bears died out in the wild, as there is little evidence from natural sites, such as caves, fens and bogs.

One scenario, based on evidence from a cave in the Yorkshire Dales, suggests the brown bear went extinct in the early medieval period - between about 425 and 594 AD.

However, there is a slim chance that the Yorkshire cave bears were descendants of bears imported into Britain from elsewhere in Europe by the Romans.

Bear cubs are spending longer with mothers

Mystery ape found in ancient tomb

How do you keep a polar bear cool?

In this version of events, bears went extinct much earlier, in the late Neolithic or early Bronze Age, with other finds coming from imported bears, alive or dead.

Whichever turns out to be true, bears have left their mark on British history through artworks, grave stones, bones, skins and museum specimens.

Bears have long had cultural importance

Bears in Britain: A brief history

Before the Ice Age

The brown bear (Ursus arctos) was once widespread across Britain, found in the wild from Devon in southern England to Sutherland in northern Scotland.

However, by the end of the last Ice Age, populations had dwindled and it had become rare.

After the Ice Age

From the Ice Age onwards, Dr O'Regan found evidence of bears (alive or dead) at 85 places in England and Scotland, from the Stone Age to post-Medieval times.

Bears were scarce in Scotland, Wales and the East Midlands, but more frequently found in Yorkshire, the east, the south and London.

There is little data from Wales, possibly because specimens have not yet been analysed.

Numbers started to decline further during the Stone Age, falling to very low numbers in the Iron Age.

Bears in Roman Britain (AD 43-410)

There appear to have been more bears in Roman Britain - suggesting live animals were imported from continental Europe.

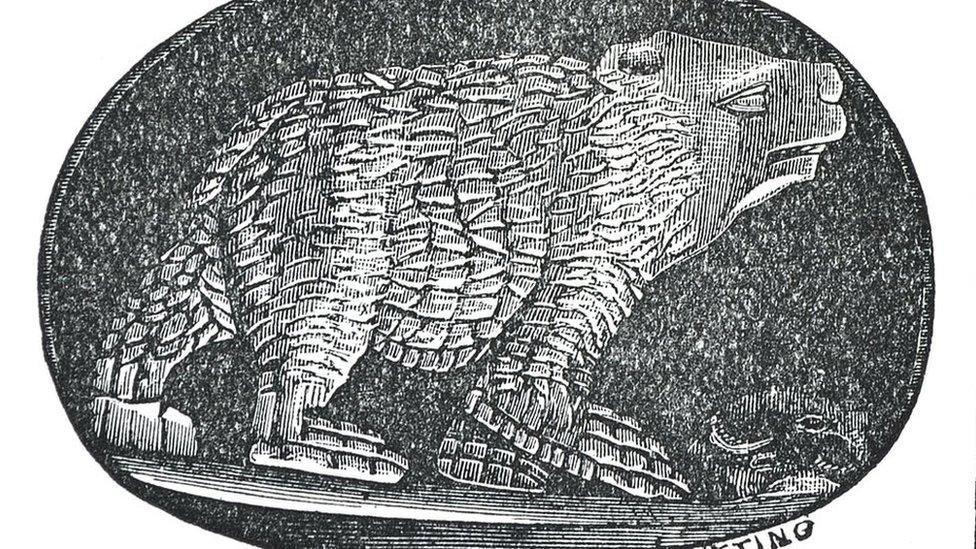

Roman Cameo found at South Shields in 1878

The fact that museum specimens from Roman times contain lots of body parts suggests live bears were probably present and used in entertainment, including bear dancing and baiting.

Early medieval times (AD 410-1066)

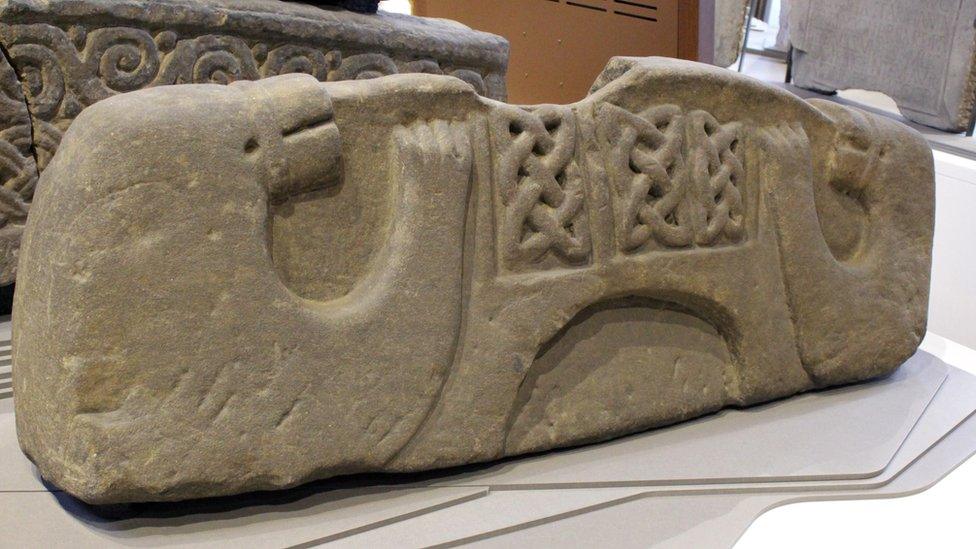

During Anglo-Saxon times, bear claws were found in cremation urns. And in the Viking Age, large carved stones called hogbacks, used to mark graves, have been found carved with bears.

Hogback stone on display at Durham Cathedral

Dr O'Regan says people may have associated the bear with certain traits, such as power.

The discovery of tiny bear figurines at children's graves suggests they might have been put there to guard and protect the occupants.

AD1066 onwards

After the end of medieval times, the only evidence for bears was found in London - because of bear-baiting arenas on the south bank of the Thames - and in Edinburgh, where specimens were kept at a medical school, possibly for teaching students.

Roman bear skull from London

Bears were present in the Tower of London and continued to be imported into Britain until well into the 20th century.

Dancing bears were a common form of entertainment. Bears were also widely used for their body parts, with bear grease still being sold in Britain in the early 20th century as a putative treatment for hair loss.

The work is published in the journal Mammal Review., external

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.