Could this 'biodegradable bag' cut plastic pollution?

- Published

It is estimated that 500 billion plastic bags are made globally every year

Plastic bags that biodegrade to nothing. It sounds like one solution to the problems of plastic pollution.

One British company that makes so-called "Oxo-biodegradable" bags said they break down in the environment "in the same way as a leaf, only quicker".

The technology is now being widely used across Africa and the Middle East.

But if it's so good, why has the EU Parliament passed a directive preventing Oxo products from being described as biodegradable? And why is the EU Commission considering a total ban?

Michael Laurier, the chief executive of Symphony Environmental, the biggest producer of Oxo products in the UK, points to a white plastic carrier bag with his company logo printed across it.

"This is an insurance policy," he says.

Symphony makes an additive called d2w, which contains a mixture of salts that is added to raw plastic in the factory.

The firm says within two years, and as long as oxygen is present, a plastic bag containing d2w will turn into something with "a different molecular structure".

"It will biodegrade in the open environment," it claims on its website.

"If you do just drop it in the ocean, we've shown that versus non-degradable products that it degrades and biodegrades an awful lot faster than conventional plastics," Mr Laurier says.

Symphony's turnover was £8.2m in 2017, its chairman is the Conservative MEP Nirj Deva and it sells to countries across the Middle East and Africa.

Saudi Arabia has even passed a law banning all single use plastic bags except those made with Oxo technology.

But the EU Commission is yet to be convinced.

In a report published in January of this year on Oxo bags, the commission concluded:

No evidence the bags will "fully biodegrade" in a "reasonable time"

Claims the bags could offer a solution to issues of littering are "not substantiated"

The bags are "not suited for long-term use, recycling or composting"

The bags are "not a solution for the environment"

The commission is being asked by the European Parliament to consider banning Oxo products by 2020.

The EU Parliament also passed a directive in April banning the term "biodegradable" in relation to Oxo technology.

It concluded, external: "Oxo-degradable plastic packaging shall not be considered as biodegradable."

Chris Packham and Oxo

In April environmentalist Chris Packham was a guest on the BBC One Show's special programme on plastics.

Raising the issue of Oxo plastics, he said: "Plastic is always going to escape into the environment. And there are technologies out there, now Oxo-biodegradable plastics, which will break down very rapidly."

The environment secretary was also on the programme.

Later in the show, Packham said: "We have answers now. And we critically need a solution now. When we've got technologies like Oxo-biodegradable."

BBC News later learned that Packham is a paid adviser to Symphony Environmental, the UK's biggest producer of Oxo additives.

But he did not declare that fact on air or to the One Show itself.

BBC guidelines say a conflict of interest "may arise when the external activities of anyone involved in making our content affects the BBC's reputation for integrity, independence and high standards, or may be reasonably perceived to do so".

In a statement, the BBC said the presenter appeared "in his capacity as a naturalist in his own right". As a private individual he was not bound by those guidelines.

The statement also said: "The One Show did not appreciate the full extent of Chris Packham's involvement with the Oxo Biodegradable industry.

"If they had been they would have made it clear on the show."

Packham's agent said his client did not want to comment on the issue.

European Green Party MEP Margrete Auken has spearheaded attempts to restrict this technology.

"The marketing of Oxo-degradable plastic as an environmentally friendly solution is absurd," she said.

"If you see anything labelled as Oxo-degradable, burn it. Reusing it will only release more micro-plastic into soil and water resources."

As for the UK government's view, Environment Secretary Michael Gove has asked the chief scientific adviser "to look at the science behind it".

Mr Gove told the One Show in April: "It's a potentially exciting development.

"But we need to be certain actually, that if we're going to put public money behind some of these schemes that we are absolutely confident that we deliver the results that the inventors and the entrepreneurs behind them are so anxious to deliver."

What do scientists say?

There have been numerous scientific reports into Oxo-biodegradable technology, but scientific opinion remains divided.

For example, a research paper from 2011, external concluded it would be possible to create Oxo bags "that will almost completely biodegrade in soil within two years".

But Richard Thompson, a professor of marine biology at Plymouth University, is sceptical. He has buried Oxo bags underground and suspended them in sea and monitored the results.

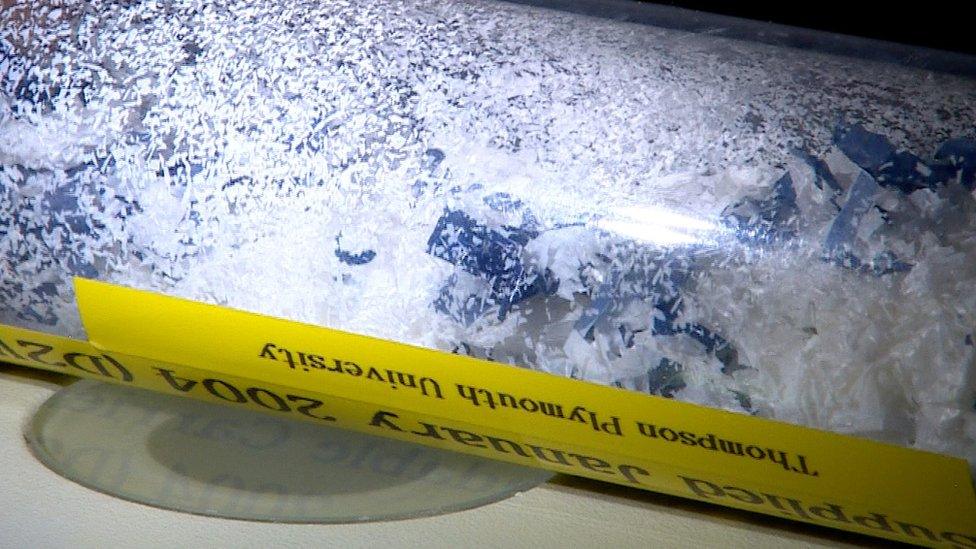

He showed a BBC team a d2w bag made by Symphony that he said had been under water in Plymouth harbour for more than two years.

"It's probably still strong enough to carry your shopping home in it," he said.

He believes there are two questions: do the bags degrade quickly enough? And when they do break down, do they in reality form microplastics?

Under a microscope he showed the BBC a bag that was more than 10 years old and had broken down into tiny pieces.

"It's degraded as a carrier bag, that bit's true. But is this an environmental solution, as what we've now got is millions and millions of very small bits of plastic?"

Mr Laurier, from Symphony, dismisses that as bad science.

"This is going to convert basically, organically to a material similar to a leaf. It couldn't be better," he said.

It is estimated that 500 billion plastic bags are made globally every year, but only 1-3% get recycled.

- Published12 March 2018

- Published5 April 2018

- Published6 June 2018