Lovell lights: turning a telescope into an art installation

- Published

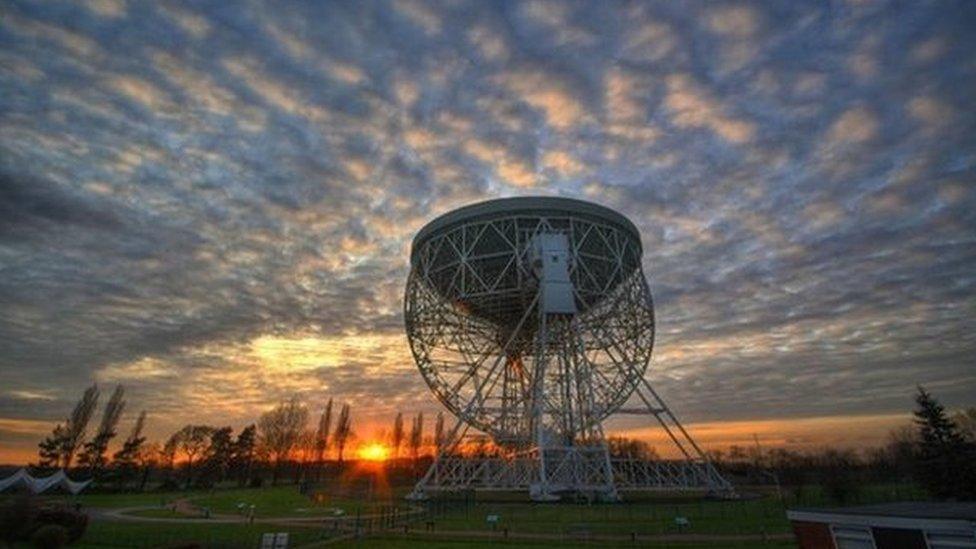

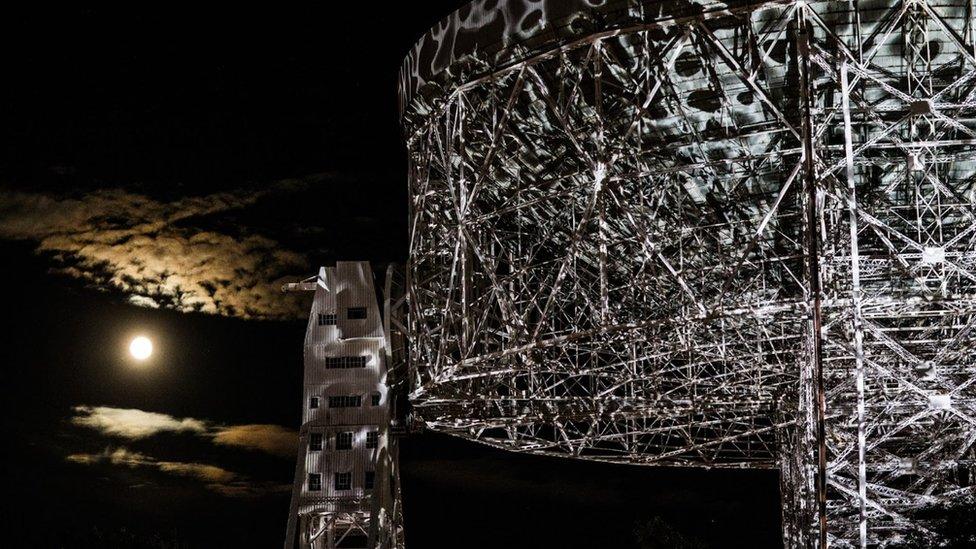

Looming up out of the green Cheshire countryside, listening to Deep Space, the Lovell telescope is an icon of science. And while it listens, the third largest radio telescope in the world becomes - for just a few days every summer - a massive, animated art installation.

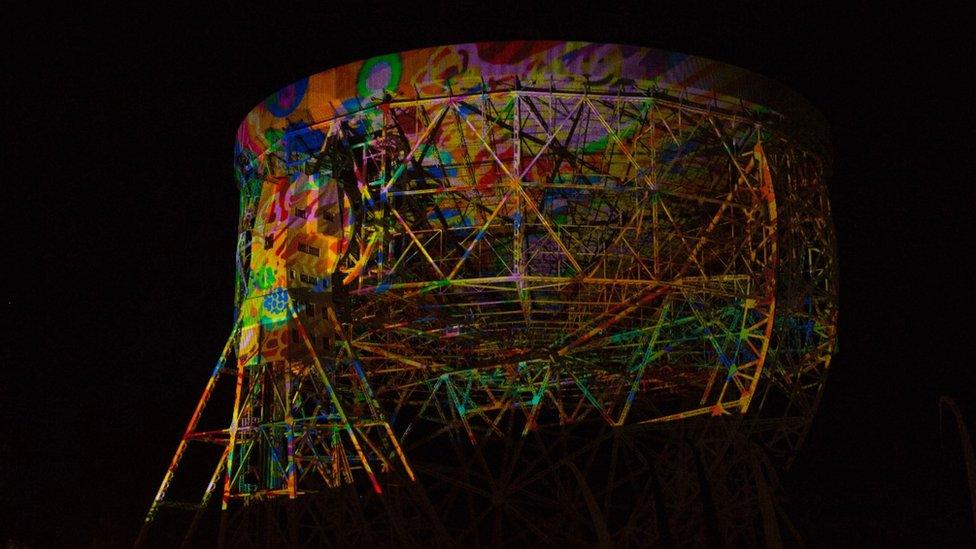

As part of the Bluedot music and science festival, external at Jodrell Bank, the telescope has now played host to displays devised by Brian Eno and Daito Manabe. The latter developed animated data which the telescope was collecting from Space, and beamed it onto the structure.

Tokyo-based artist, DJ and programmer Daito Manabe used data that Lovell was gathering from deep space to create an animated light show.

This year it will host two specially commissioned projection pieces - one inspired by the possibility of extraterrestrial life, external.

Making artists' work come to life on a big, complicated steel structure has been the task of Pod Bluman, who is in the business of building "visual experiences".

US artist Addie Wagenecht’s 2018 Lovell-based work is titled Hidden in Plain Sight

"The first time we did this with the Lovell Telescope, we were working with Brian Eno," he told BBC News.

"The (inside of the bowl) provided us with a huge screen, so we just projected content at the bowl and hoped that content would work."

The Lovell Telescope takes centre stage at the Bluedot festival

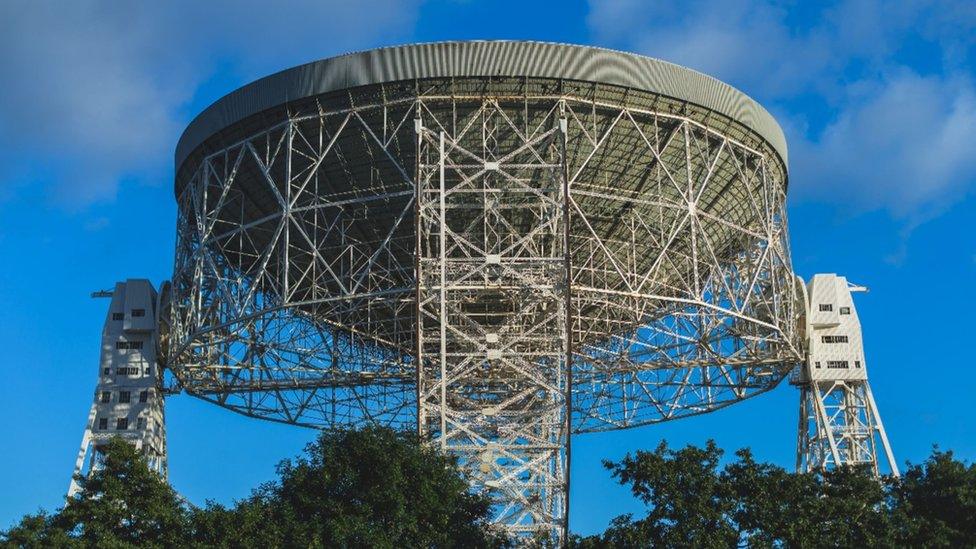

For the last two years though, Lovell's 5,000 square metre bowl has been undergoing restoration, which means it has to be kept static and pointed directly upward. As a result, artists and designers are deprived of its huge circular "screen".

"All we had was the superstructure, so we convinced the powers-that-be that we needed a 3-D scan of the whole thing," said Mr Bluman.

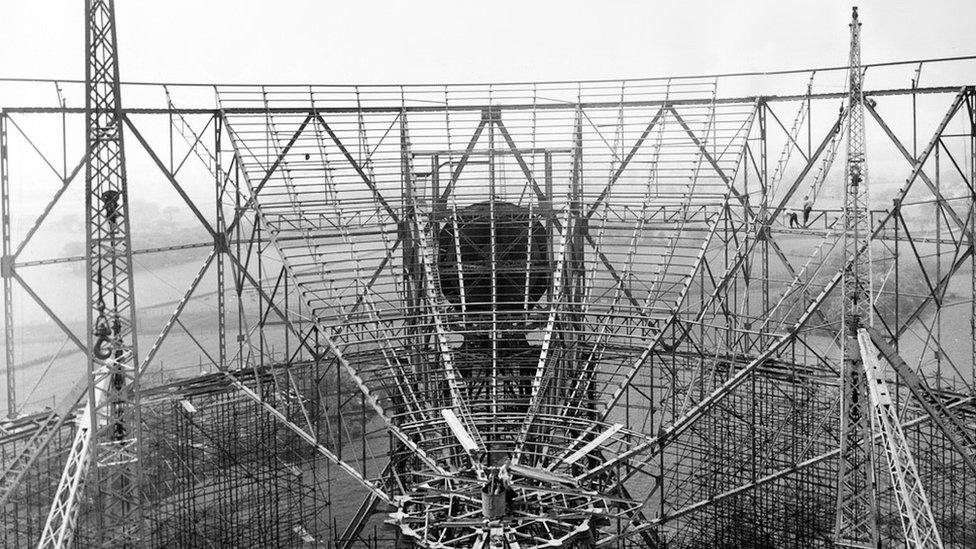

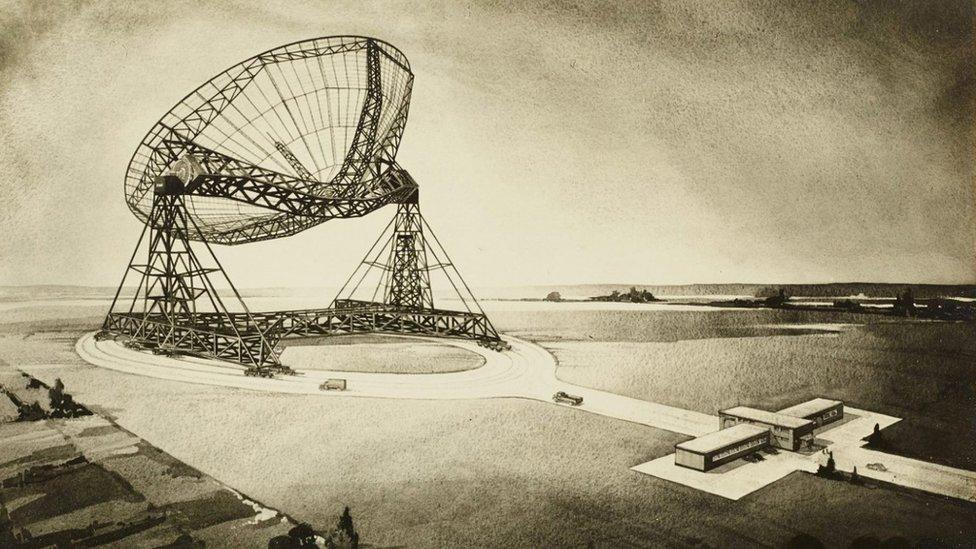

The need for that scan dates from when construction first began on Professor Bernard Lovell's great telescope in 1952. Even as the structure took shape, there were many unsolved engineering problems.

The construction of what was originally named the Mark I Telescope required using racks from battleships to steer the huge dish

Many ad hoc solutions that allowed the 1,500 tonne bowl to be steered with pinpoint accuracy were devised along the way, including the use of racks from battleship gun turrets. Possibly as a result of these swift engineering fixes during construction, there were no accurate technical drawings of the telescope available.

"We used a Lidar scan, which essentially shoots lasers at the entire telescope to create an enormously detailed point cloud - a three-dimensional map of the structure," Mr Bluman explained.

Once he and his team had simplified this map, they used it to virtually "flatten out" the whole structure into a two-dimensional plan, and used that to design the animations that would be projected onto every single strut.

There were no detailed technical drawings available of the Lovell Telescope

When that 2-D animated plan was "remoulded" back into a 3-D telescope - complete with its mapped-on animations - the team could convert that into a scheme of exactly where every projector should be positioned to fill each strut's surface with images.

Dr Teresa Anderson, director of the Jodrell Bank Discovery Centre, said that ever since she and her team began running cultural events on the site more than a decade ago, the idea of using the Lovell Telescope was something that had "absolutely fascinated artists".

Every strut and its position had to be mapped in order for the animation to be accurately projected onto the telescope

"It's so big - as tall as the clock tower of Big Ben - so it's an amazing edifice as well as a scientific instrument.

"And once you start thinking about what it's doing - listening to the Universe - it becomes even more fascinating."

So what does she think Sir Bernard Lovell would have thought of his great scientific achievement becoming a giant light show during a festival?

"He was someone who understood the importance of people feeling connected to science - of bringing the public in and giving them a sense of ownership of the work we do here," said Dr Anderson.

"So I think he would have really supported it.

"But he wasn't a fan of 'popular music', so he might have had ear plugs in for the bands."

- Published12 October 2017