A bird's eye view: Songbirds perceive colour like humans

- Published

Faced with a glorious spectrum of colour, songbirds, just like humans, look for the big picture.

They can lump nearby hues in the colour spectrum into categories, such as shades that are generally red, or generally orange.

A study now shows that this affects their ability to distinguish between certain colours.

The findings, by a team from Duke University in North Carolina, are published in the journal Nature., external

Female songbirds were rewarded with food if they flipped over a circular disc of two colours.

The two-colour discs had different pairs of colours selected from an orange-to-red spectrum. This mirrors the colour range found in the male songbird beak.

One idea was that the birds would be able to pick up on all detectable differences in colour across the spectrum. But instead, the birds do something known as "categorical perception".

This means that they respond more if the difference in colour between the two halves of the disc is between distinct colour categories, so that one is distinctly orange and the other distinctly red.

However, shades that were close to one another on the spectrum did not get such an obvious reaction.

It happens in primates, including humans, but this is the first time that another animal has been shown to exhibit categorical perception of colour., external

Duke University scientists Drs Eleanor Caves and Patrick Green, who conducted the experiments, came up with the idea over dinner with senior author Professor Stephen Nowicki.

Dr Caves recalled: "We read a paper about categorical perception in infants and thought, if you don't need language for categorical perception, maybe animals can do it."

Female songbirds were trained for the study. They were rewarded if they flipped over a circular paper disc of two colours to reveal food. If it was a single-colour disc they got nothing.

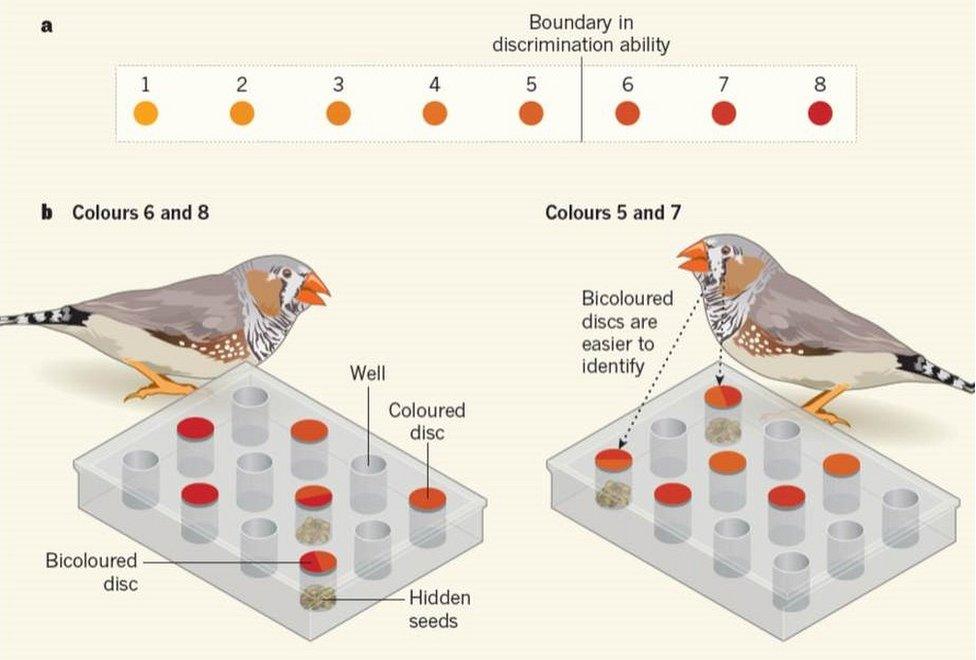

The researchers made use of eight colours in the orange-to-red spectrum (see graphic above) and made a variety of discs with different pairings of these colours. The scientists tested to see if the position of the disc's colour pair on an orange-red spectrum had an effect on the bird's ability to discriminate between the colours.

There is a point or a boundary in the transition from orange to red shades in their study. They could see that the birds could best discriminate between the two colours on the disc when they were far apart on the spectrum. They did it especially well if the colours were located on either side of this "boundary line".

Mr Perfect or Mr Good Enough?

The colours used in the study were picked because the male zebra finch's beak is coloured red or orange. The colour is based on carotenoids - the family of natural pigments found used by a variety of animals and plants.

Female zebra finches prefer a male mate with a red beak more than an orange beak.

"Zebra finches are well known as using the carotenoid-based colours as a signal. Females prefer beaks that are redder. Males use the red-orange colouration as a way of establishing dominance," said co-author Patrick Green.

The ability to lump colours on one side of a redness threshold may mean that the female gazing at the beak colour of a potential mate is not particularly fussy about him being the perfect red.

Red "enough" may be good enough.

Patrick Green added that for a female choosing a mate "relatively simple rules for perceiving colouration might make a lot of sense for simplifying information and coming to a good choice". Future experiments will be able to test this idea.

Eleanor Caves said: "Vertebrates cannot make their own carotenoids and have to ingest compounds that have carotenoids in them. That might make a male more superior over another one. He is able to find and ingest these carotenoids. So maybe he lives in a better territory or he is a better forager.

She added: "The enzyme that metabolises the carotenoid into the compound that becomes red colouration is the same enzyme as an important immune pathway."

So it could be that redder colouration of the beak is a visual signal to the female birds, probably about male biological "fitness" - which includes how robust the male's immune system is.

"It's hard to fake. A poor quality male couldn't just decide to put more energy into making a red beak," said Dr Caves.

Why does it matter?

Categorical perception of colour hasn't been demonstrated before in birds. The study suggests that it isn't caused by how well the light-sensitive cells in the bird's eyes distinguish difference wavelengths of colour.

Instead, it may be how the signal from the eye is processed in the brain. It could be a way of allowing the zebra finch to focus on key sensory cues. It may also be a way of animals handling a vast amount of sensory input - helping them to make choices.

Some researchers think that you have to be able to describe categories of colour using language before the categories be distinguished from each other quickly and accurately. But human infants can differentiate between red, green, blue, yellow and purple before they have the words in place to name these colours.

And this new study supports another way of thinking: that colour perception may have deeper biological roots than just language and culture.

"Categorical perception has now been found in everything from facial identity recognition, to frog calls, cricket calls and zebra finch visual signals," said Eleanor Caves. "It is looking more wide spread than we would have guessed."

Follow Lucy on Twitter., external