Winged reptiles thrived before dinosaurs

- Published

A 3D printed model of the pterosaur skull discovered in Utah

Palaeontologists have found a new species of pterosaur - the family of prehistoric flying reptiles that includes pterodactyl.

It is about 210 millions years old, pre-dating its known relatives by 65 million years.

Named Caelestiventus hanseni, the species' delicate bones were preserved in the remains of a desert oasis.

The discovery suggests that these animals thrived around the world before the dinosaurs evolved.

The pterosaur is a close relative of Dimorphodon, discovered by Mary Anning on Britain's Jurassic Coast

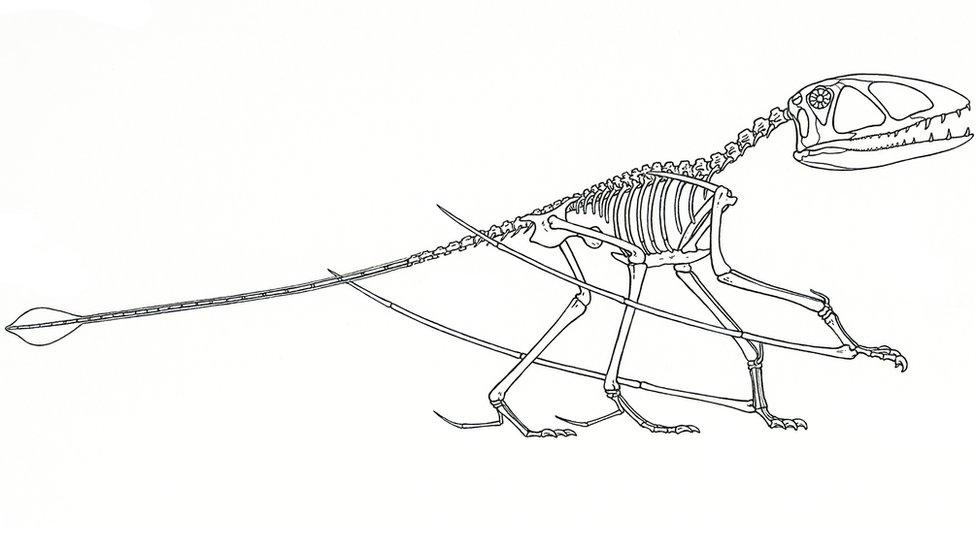

Pterosaurs are the oldest flying vertebrates; the first to crack the evolutionary puzzle of powered flight.

As a result of this engineering, their delicate, bird-like skeletons are often found in quite a crushed state.

"Most of them are heavily distorted; literally like roadkill," says lead author Prof Brooks Britt, from Brigham Young University in Utah.

Finding the perfectly preserved skull of this early species provided researchers with a rare opportunity to study its structure.

The 3D model shows the pterosaur's teeth in great detail

"The bones are so delicate, you can't take them all the way out of the rock because they would just fall apart," explains Prof Britt.

Instead, the team used a CT scanner to build a digital profile of the skull, and then printed a detailed 3D model.

This revealed a remarkably complex set of teeth, including sharp fangs protruding from the front of the mouth, and blade-like teeth along the lower jaw.

Analysis

Dr Steve Brusatte, University of Edinburgh

Finding a pterosaur in an ancient Triassic-aged sand dune is a hugely pleasant surprise.

What makes this discovery so remarkable is that very few pterosaurs are known from the entire Triassic Period, which means that we have few fossils that tell the story of how these strange winged reptiles evolved during the first 30 million years of their history.

It's a trifecta: a Triassic pterosaur from a new place, preserved in an immaculate way, and found in rocks from an environment that we didn't think they lived in so early during their evolution. What this means is that pterosaurs were already geographically widespread and thriving in a variety of environments very early in their evolution.

They were not a fringe group restricted to a few habitats while their dinosaur cousins were rising up, but they were part of the fabric of the Triassic world, along with the earliest dinosaurs.

The new species is most closely related to an Early Jurassic-aged British pterosaur, which means that these primitive pterosaur groups not only were widespread, but they survived the great extinction at the end of the Triassic, when volcanoes welled up through the cracks of the fracturing supercontinent Pangaea and caused a runaway global warming event that may be similar to what we're experiencing today.

The fossils come from a quarry in the Utah desert that was once a bustling oasis, about 210 million years ago.

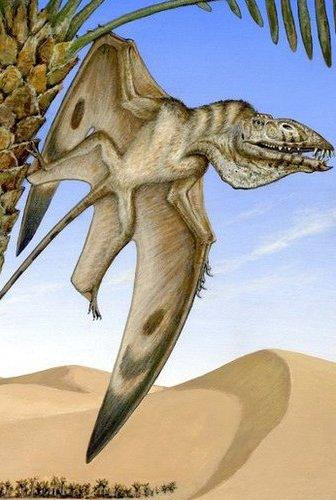

Artist's impression of Caelestiventus hanseni

"This one site we've pulled out 18,000 bones from an area the size of a good sized living room," says Prof Britt. "And there's only one pterosaur."

The specimen had not yet reached adulthood, but had a one-and-a-half metre wingspan.

"It was probably the biggest of its day. Among its peers, we have no evidence that any rival came close to that," adds Prof Britt.

The pterosaur may have hunted small vertebrates living in the underbrush around the oasis, and there are signs that it had a throat pouch similar to some modern birds.

Now, the team plan to do further research on the fossil, to better understand how it lived and what it ate.

The findings have been published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, external.

Follow Mary on Twitter, external.