Plastic pollution: 'Stop flushing contact lenses down the loo'

- Published

Researchers in the US have been investigating the final journeys taken by disposable contact lenses.

They found 15-20% of US users simply flick these fiddly lenses down the drain via the bathroom sink or toilet.

The Arizona State University study suggests that much of the plastic material then ends up in waste water treatment plants.

The lenses are consequently spread on farmland as sewage sludge, increasing plastic pollution in the environment.

Around 45m people wear contacts in the US, while rates in other countries vary, with between 5 and 15% of the population in Europe using them.

Over the last decade, the use of softer plastic contact lenses has grown rapidly with people using daily, weekly or monthly disposables in greater numbers than ever before.

This new study suggests that in the US at least, around 14 billion lenses are thrown away, amounting to around 200,000kg (441,000lb) of plastic waste every year.

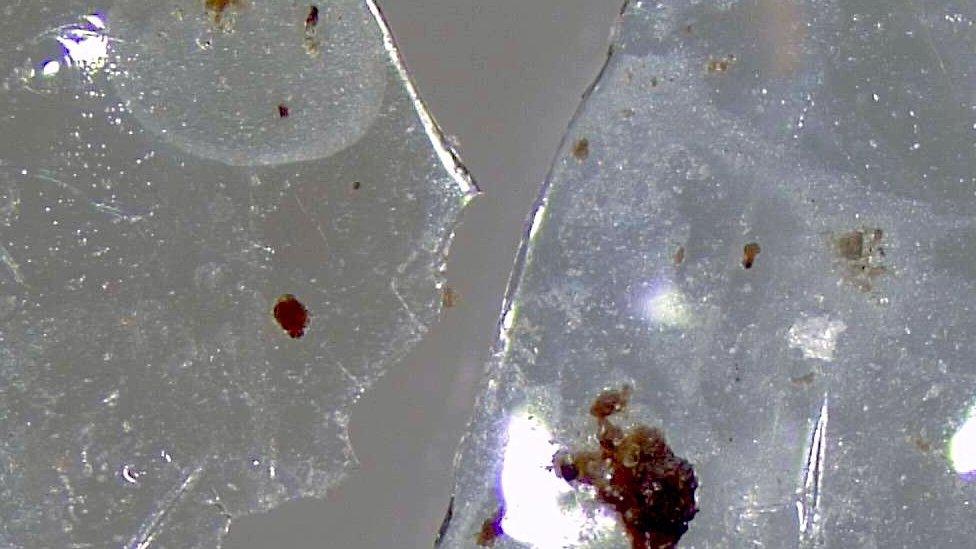

A contact lens recovered from sewage sludge

The authors of the study surveyed wearers in the US and found that 15-20% of them flick their lenses down sinks and toilets, meaning they will most likely end up in waste water treatment plants.

Much of the waste water material ends up as a digested sludge which is then often spread on farmland. The authors estimate that around 13,000kg of contact lens plastic ends up deposited in this way.

"They persist during water treatment, they become part of sewage sludge," Prof Rolf Halden, from the Centre for Environmental Health Engineering at Arizona State told BBC News.

"We know that whatever's in sludge can make its way into runoff from heavy rains, back into surface water and that is a conduit to the oceans; there is the potential of these lenses being taken on quite a journey."

Contact lenses can accumulate in sewage sludge before it is spread on farm land

The researchers are concerned that this poses an ecological risk and may allow the accumulation of persistent toxic pollutants in vulnerable organisms such as worms and birds.

"If earthworms consume the soil and birds feed on it, then you could see that plastic make the same journey as is done by plastics debris in oceans, they are incorporated by biota that are also part of the human food chain," said Prof Halden.

Contact lenses are often made from a mixture of acrylic glass, silicones and fluoropolymers that allows manufacturers to create a softer plastic material which permits oxygen to pass through to the eye.

To work out the impact of waste water plants on these materials, the researchers exposed five polymers in contact lenses to anaerobic and aerobic micro-organisms commonly found in these treatment facilities.

Lenses will dry out quickly and shatter forming smaller pieces of plastic

"We found that there were noticeable changes in the bonds of the contact lenses after long-term treatment with the plant's microbes," said Varun Kelkar, one of the authors from Arizona State University.

"When the plastic loses some of its structural strength, it will break down physically. This leads to smaller plastic particles which would ultimately lead to the formation of microplastics."

The researchers want manufacturers to provide information on the label, informing people how to properly dispose of their contacts.

Lenses are not generally recycled, although one of the largest manufacturers Bausch + Lomb introduced a programme , externallast year.

The authors of the study say that lenses should be recycled where this is possible, but if not they should be disposed of by putting them in with other solid, non-recyclable waste.

"The simple fix to this is for people not to put the lenses down the sink or shower or toilet!" said Prof Halden.

"They are a real improvement in quality of life and are a justified use of plastic, so if we decide as a society that we want to use plastic for these purposes, we should also present the consumer with the chance to get rid of these materials in a responsible fashion."

The research has been presented at the national meeting of the American Chemical Society, external in Boston.

- Published4 August 2018