The life of a shark scientist

- Published

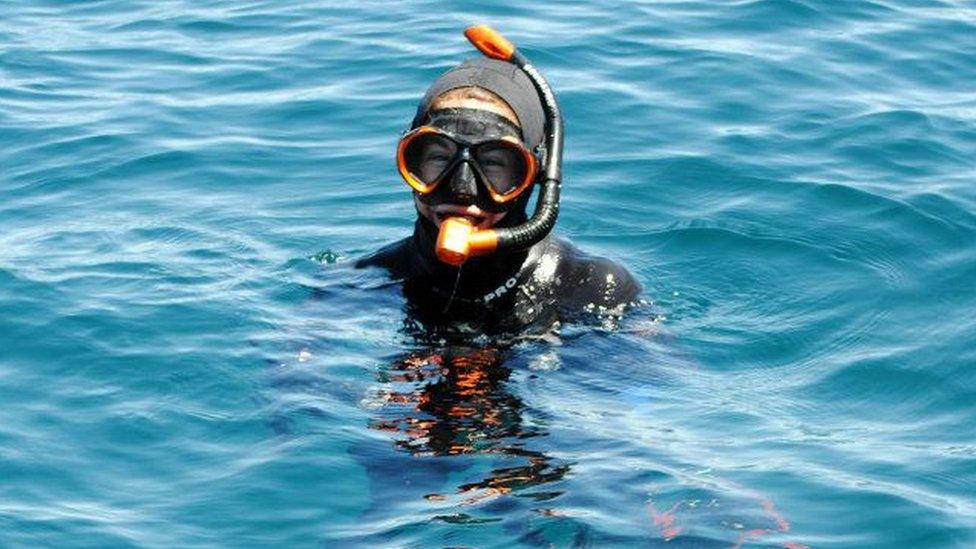

A marine biologist, in her natural habitat

What do marine biologists do all day?

It's not all about time in the ocean, though Melissa Marquez often wishes it was!

A marine biologist and shark researcher based in Sydney, she has given BBC News a quick guide to ocean research, some of the Great Barrier Reef's residents, and what to do to if you get bitten while scuba diving.

What made you decide to focus your research on sharks?

I've always had an interest in misunderstood predators, and sharks just happen to be the most misunderstood.

When I was about seven, I put on [the Discovery Channel's] Shark Week. I remember seeing a great white shark breaching - so flying through the air, essentially - and I was hooked. By the end of the show I was like: that's what I want to do, I want to study these animals.

Heron Island, on the Great Barrier Reef

How much time do you spend in the ocean? Can you tell me about a recent dive?

It depends what kind of research one is doing, and how often you can get out.

I've always wanted to dive in the Great Barrier Reef, [so we went to Heron Island in August].

It has a very low percentage of bleaching and it's quite a healthy looking area right now.

The coral reef surrounding Heron Island

I was actually there for the blacktip reef sharks. There were a lot of juveniles in that area, so I was kind of tracking to see if there's a nursery in that area and to see what factors make a nursery area favourable. I'm putting together a PhD project at the moment and I'm capturing pictures of all sharks here for a possible population study!

A young blacktip reef shark

Setting up the dive is more important than anything... making sure you and your dive partners have a plan.

[But] I think the biggest thing I try and do when I'm diving is have fun... because a lot of people don't get the opportunity to see what's below the waves in such an intimate way.

"Hello... from underwater! Scuba diving is one of my favourite hobbies, and I love using my GoPro to capture pictures of animals beneath the waves."

Usually, dives are anywhere from 30 to 50 minutes: I'm always upset when the time is up.

"Here we are on the hunt for epaulette sharks, who use the low tide to seek out food. Do you spot the one here?"

I thought we were going to have a hard time spotting epaulette sharks, but they were everywhere! The epaulette shark uses its pectoral fins and pelvic fins… they actually allow this shark to kind of walk!

If it gets stranded at low tide it can walk out of one little puddle into another puddle. It's able to withstand very low oxygen environments for a time.

They are also masters of camouflage!

[We also saw] a cowtail stingray. That one was right as we were going into the water which was really cool.

All stingrays have a venomous barb near the base of the tail. They only use it for self defence.

So this is my first time diving after that initial dive in Cuba after I got bitten, external [in April].

"If you watched Shark Week 2018, you saw I was bitten by a 3m American crocodile! This is the same suit... except I had the other leg cut off to make it a shortie. Perfect for diving in the tropics!"

I'm pretty sure my parents expected for a shark to bite me, not a crocodile.

Had you ever considered the possibility of a shark bite?

You know... no! I know it's a possibility, I know it's always going to be a possibility especially with the line of work that I do.

The reason I say no is because I'm really careful, and I know you can be the most careful… with the crocodile, we had every safety measure in there and yet it still happened.

But, for the majority of it, they're not freak accidents. Usually someone is at fault or someone has done something, like people swimming in a group of shiny fish, or swimming in really murky water where there's fishermen cleaning their catch up the current.

I know it's a risk, but I know it's a small risk and I know what to do if that happens.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

What do you do?

It depends. A lot of people say to try and punch the shark in the snout. But I don't know if you've ever punched anything underwater? You're very slow.

I think the last thing you want is your arm or your hand near the teeth. [Sharks] are not slow underwater, they are quite fast underwater.

So, I would say that you would want to punch it in the gills. It's basically like punching it in the lungs and it will definitely not want to deal with you if you are punching it repeatedly in the gills, where it breathes.

Allow Instagram content?

This article contains content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Instagram cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

So punching a shark is literally the advice if you get grabbed by one?

Yes, to be honest I wouldn't play dead with them! The same exact thing with the crocodile; if the crocodile had been more aggressive, I would have fought back.

The fact that [the bite] felt like really really really hard pressure, but not actually enough to make me cry out in pain, means that it was definitely an exploratory bite.

You definitely have to read the situation you're in, but more often than not I would say fighting back against a shark is what you would want to do.

But shark bites are so rare. You've got a bigger chance of a vending machine squishing you or getting hit by a coconut than you ever do of encountering a shark bite.

I've gone diving with four-metre sharks, no cage whatsoever, swimming belly to belly with them. No fear.

The Great Barrier Reef's Heron Island at sunset

What's the one thing you would like people to know about sharks?

I think the one thing would be that we need sharks a lot more than most people think. They are a really important part of the oceanic ecosystem. And if you take this predator out of the equation, you're basically going to make it so that this ecosystem falls apart in multiple ways.

The fact that our planet is covered by water, specifically oceanic water... you wouldn't want that ecosystem to fall apart.

So, I think the one thing I would want people to know is just how important they are.

You can follow Melissa's work on Twitter, external and Instagram, external.