Why Sulawesi's tsunami is puzzling scientists

- Published

The quake was large - but not of the type normally associated with a big tsunami event

Friday's catastrophic tsunami event on Sulawesi Island is a puzzle.

As the emergency response gathers pace, scientists are scratching their heads to understand why it generated such big waves.

The magnitude 7.5 quake was certainly large - one of the biggest recorded anywhere on the globe this year.

But it was what geophysicists call a strike-slip event, where the ground breaks horizontally. In this instance, the rock to the east of the fault running up through the island moved northwards relative to the rock to the west.

Strike-slip quakes can cause tsunami events but the 6m-tall waves that crashed ashore at Palu city surprised everyone.

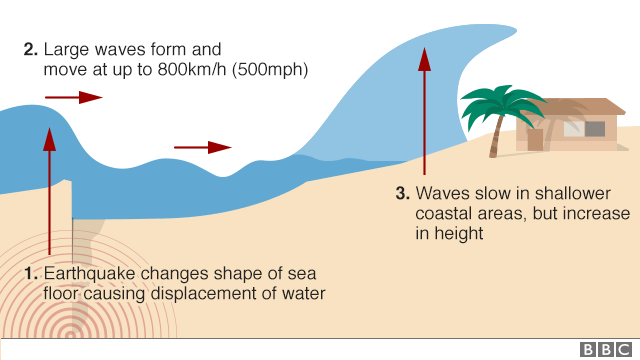

Remember that to make the series of waves you need a big displacement of the sea-floor - a vertical movement that disturbs the entire water column, which then moves away in all directions.

Some early calculations suggest a floor displacement of perhaps half a metre. Significant but generally insufficient to produce the waves that were recorded.

So what happened? Two factors are emerging as possible culprits. They may even have worked hand in hand.

The first is the suspicion that the quake triggered some sort of underwater landslide.

These are an ever-present danger. A quake can destabilise large collections of sediment and cause them to break free of their footing and tumble downslope.

In mountainous areas on land, rock and sediment avalanches are major earthquake hazards that rival the destruction from collapsed buildings. But underwater, these movements of sediment have the potential to also generate tsunami events.

When this happens, the waves that hit shorelines can be large, even if the effects are fairly localised.

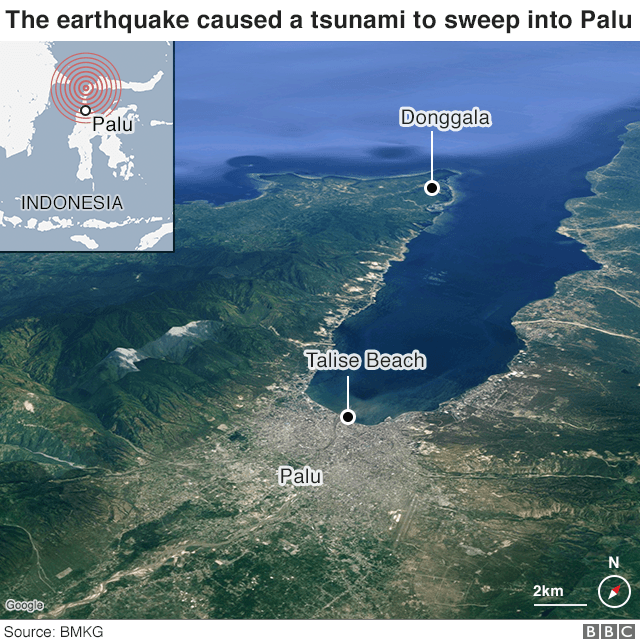

This may have been what happened on Friday, and perhaps the waves were then exacerbated by the shape of Palu bay itself. It has an elongated geometry, which could have focused and amplified the tsunamis as they approached the city's Talise beach.

This is all conjecture, of course. The science community, as we speak, will be modelling Friday's event to try to tie down the details of the generation and propagation processes involved.

"My first calculations of the seafloor deformation in the earthquake are 49cm," said Dr Mohammad Heidarzadeh, an assistant professor of civil engineering specialising in coastal engineering at Brunel University in the UK.

"From that you might expect a tsunami of less than one metre, not six metres. So something else is happening. So the two speculations are legitimate - the submarine landslide and the funnelling caused by the bay."

A straightforward way to assess any changes on the seafloor is to carry out a bathymetric survey. This would ascertain pretty quickly whether there has been significant movements of sediment.

As to onshore landslides, these will be mapped from satellite.

Satellite imagery shows districts swept away in lateral movements of sediment

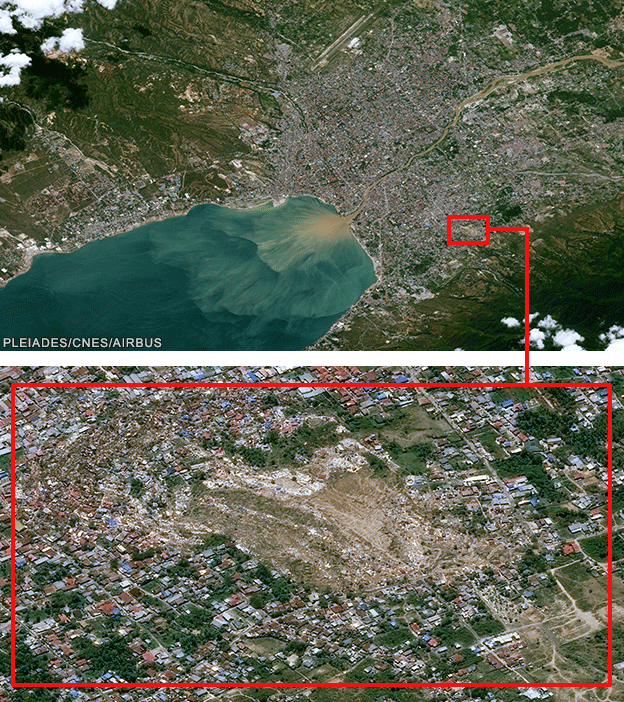

You may have seen some remarkable videos at the weekend of whole swathes of ground moving laterally in front of the camera.

In one video, an antenna is seen to slide in front of someone's mobile phone

In one, a tall antenna eerily marches across the landscape, external; in others, buildings drift sideways as if suddenly caught afloat on a river.

The locations of many of these videos have now been identified, and from the earliest space imagery it is possible to discern places where whole districts of Palu have been picked up and dumped into vast piles.

"If you look at the satellite imagery, you can see that there are masses of houses compressed into a small zone, leaving behind a bare area of ground behind where the houses once were," explained Prof Dave Petley, a landslides expert at Sheffield University, external.

"This looks like classic 'liquefaction', where the structure of soil has collapsed; it's fluidised and you get these very active landslides on a low gradient," he told BBC News.

Everything should become clearer in the coming days and weeks as researchers get into the region to assess the impacts of both the quake and tsunami.

The world's fleet of satellites have also been tasked to get as much imagery as possible. This will be tricky because Sulawesi is on the equator and there is likely to be a lot of cloud in the sky which will frustrate optical satellites.

But there will be overpasses by radar spacecraft as well, and these see the ground in all weathers, day and night.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external