German satellites sense Earth's lumps and bumps

- Published

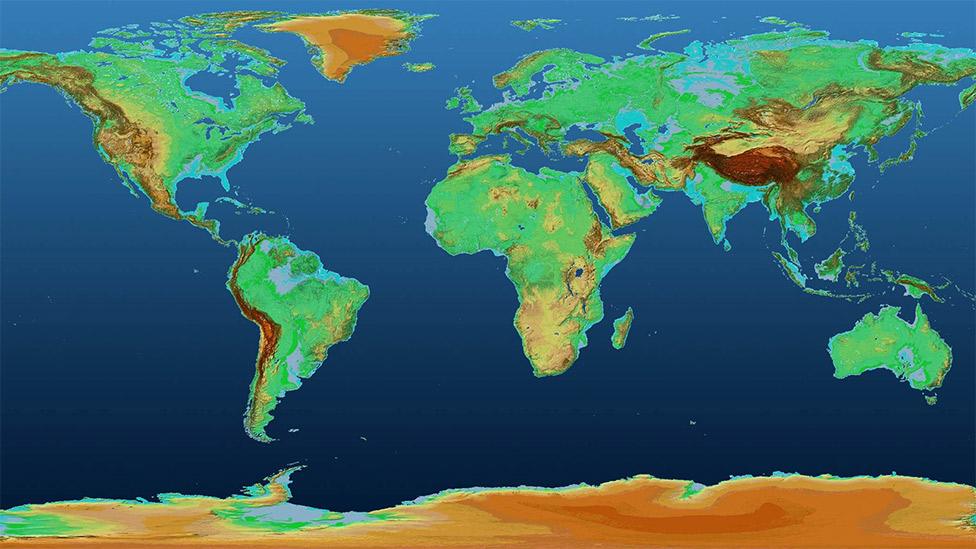

The map traces the variations in height across the Earth's land surfaces

The German space agency (DLR) has released a spectacular 3D map of Earth.

Built from images acquired by two radar satellites, it traces the variations in height across all land surfaces - an area totalling more than 148 million sq km.

DLR is making the map free and open, enabling any scientist to download and use it.

There will be myriad applications, from forecasting where flood waters flow to planning big infrastructure projects.

How was the map made?

The two satellites involved are called TerraSAR-X and TanDEM-X.

Like all radar spacecraft, they send down microwave pulses to the surface of the planet and then time how long the signals take to bounce back.

The satellites fly close to each other some 500km above the Earth

The shorter the time interval, the higher the ground. TerraSAR-X and TanDEM-X fly virtually side by side, sometimes coming to within 200m of each other.

This is complex to control, but it gives the pair "stereo vision", by allowing them to operate an interferometric mode in which one spacecraft acts as a transmitter/receiver and the other as a second receiver.

Tibet in the Himalaya. The images use colour to denote elevation. Red is high; blue is low

How precise is the map?

The resolution of the newly released digital elevation model (DEM) is 90m, external, meaning the land surface has been divided up into squares that are 90m along the side.

The absolute accuracy in those squares in the vertical dimension is 1m, making the DEM a powerful rendering of all the Earth's lumps and bumps.

There are DEMs that have far higher resolution on regional scales, but this new product beats any other global, publicly available dataset. It also has no gaps.

The Sahara desert, showing part of the Tamanrasset province of central Algeria

What are the next steps?

DLR has other versions of the map whose sampling squares are 30m and 12m across, but these are - for the time being - commercially restricted.

TerraSAR-X and TanDEM-X continue their mapping exercise.

Having a static DEM is great but the shape of the Earth's surface is always changing and this needs to be captured as well.

The orbiting pair are now getting quite old. TerraSAR-X was launched in 2007 and TanDEM-X was launched in 2010.

DLR hopes to keep them running for a good few years yet, but planning for the replacements is well advanced.

The northern Appalachian Mountains in the US state of Pennsylvania

What comes after these satellites?

The future mission would be slightly different in that the radar instruments would operate not in the X-band but in the L-band - a longer wavelength.

This would facilitate different types of application. "In forests, for example, in the X-band you get, more or less, the top of the canopy," explained Dr Manfred Zink from DLR's Microwaves and Radar Institute, external.

"You don't penetrate and see under the leaves. But with the L-band we will penetrate; we will see the solid ground. That would enable us to see the vegetation volume in real 3D. It's tomography," he told BBC News.

"We would see the full vertical structure of the forest and that is key for precise biomass estimates."

Knowing exactly how much carbon is tied up in the world's forests is a big unknown, but vital for climate change assessments.

Another application in the L-band would be to sense better the way the ground deforms during an earthquake.

Scientists do this already using radar satellites operating at other wavelengths, but their observations can often be difficult to interpret in places where there is a lot of vegetation growth.

TanDEM-L, as the future system will be known, would hope to get around some of these difficulties.

Glaciers flow towards the Weddell Sea on the eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external