Humans 'off the hook' for African mammal extinction

- Published

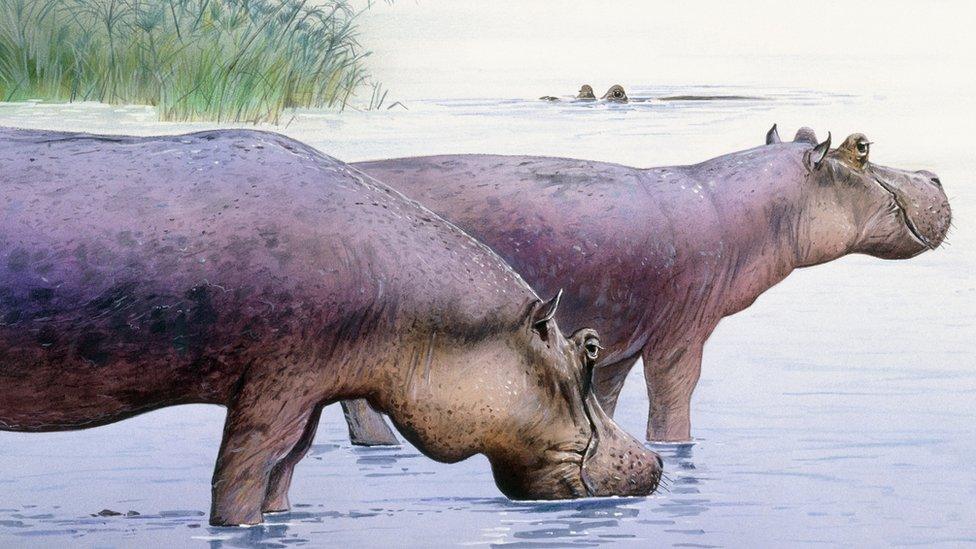

Artwork: The extinct Hippopotamus gorgops was bigger than modern hippos, reaching lengths of 4.3m

New research has disputed a longstanding view that early humans helped wipe out many of the large mammals that once roamed Africa.

Today, Africa broadly has five species of massive, plant-eating mammal; but millions of years ago there were many more types of giant herbivore.

Why so many types vanished is not known, but many experts have blamed our tool-using, meat-eating ancestors.

Now, researchers say the mammal decline began long before humans appeared.

Writing in the journal Science, Tyler Faith, from the Natural History Museum of Utah, and colleagues argue that long-term environmental change drove the extinctions.

This mainly took the form of an expansion of grasslands, in response to falling atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels.

"Despite decades of literature asserting that early hominins (human relatives) impacted ancient African faunas, there have been few attempts to actually test this scenario or to explore alternatives," said Dr Faith.

A transition from eating mainly vegetables and fruit to predominantly eating meat may have driven the evolution of humans' big brains. This transition occurred in concert with the development of stone tools, which would have allowed our ancestors to butcher the carcasses of animals; either as scavengers or hunters.

Artwork: The extinct giraffe Sivatherium maurusium vanishes from the fossil record around 700,000 years ago

To investigate whether humans played a role, the researchers compiled a seven-million-year record of herbivore extinctions in eastern Africa. They focused on the very largest species, the so-called "megaherbivores" which weigh more than 2,000lbs (907kg).

Today, only elephants, hippos, giraffes and white and black rhinos fall into this category.

But the three-million-year-old human relative "Lucy" (Australopithecus afarensis) shared her East African habitat with three species of giraffe, two species of rhino, a hippo and four elephant-like species.

Australia extinction 'due to man'

Human link to giant turtle's end

The results of the analysis showed that over the last seven million years, some 28 lineages of large mammal went extinct in Africa.

Furthermore, the onset of the herbivore decline began roughly 4.6 million years ago, and the rate of decline did not change following the appearance of Homo erectus, one of the earliest human ancestors that could have contributed to the extinctions.

"This extinction process kicks in over a million years before the very earliest evidence for human ancestors making tools or butchering animal carcasses and well before the appearance of any hominin species realistically capable of hunting them, like Homo erectus," said Dr Faith.

The fossilised jawbone of a sabre-toothed cat from South Africa. The disappearance of massive herbivores may also have affected the carnivores that fed on them

The researchers also examined records of climatic and environmental trends. They conclude that the climate is a much more likely culprit than humans. Climate change seems to have been behind the replacement of large shrubs and trees by grasslands.

"The key factor in the Plio-Pleistocene megaherbivore decline seems to be the expansion of grasslands, which is likely related to a global drop in atmospheric CO₂ over the last five million years," said co-author John Rowan, from University of Massachusetts Amherst.

"Low CO₂ levels favour tropical grasses over trees, and as a consequence savannas became less woody and more open through time. We know that many of the extinct megaherbivores fed on woody vegetation, so they seem to disappear alongside their food source."

The loss of big mammals in Africa could also explain other extinctions that have been blamed on our ancient ancestors.

For example, some scientists have suggested that increasingly carnivorous early human groups led to a decline in predators and scavengers.

"We know there are also major extinctions among African carnivores at this time and that some of them, like saber-tooth cats, may have specialised on very large prey, perhaps juvenile elephants," said co-author Prof Paul Koch from the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC).

"It could be that some of these carnivores disappeared with their megaherbivore prey."

Writing in the same issue of Science, René Bobe and Susana Carvalho from the University of Oxford raised a few words of caution over the conclusions: "It is not clear what ecological roles hominins played throughout the long evolutionary history of megaherbivores in Africa, and how these roles changed over time and varied across geographic space.

"Another question is when hominins became systematic predators of animals larger than themselves."

They added: "The causes of megaherbivore decline are probably complex, multidimensional, and varied across time and space. The precise timing of key hominin behavioural innovations remains poorly constrained by the current archaeological and palaeontological records."