Nation's botanical treasure troves 'under huge threat'

- Published

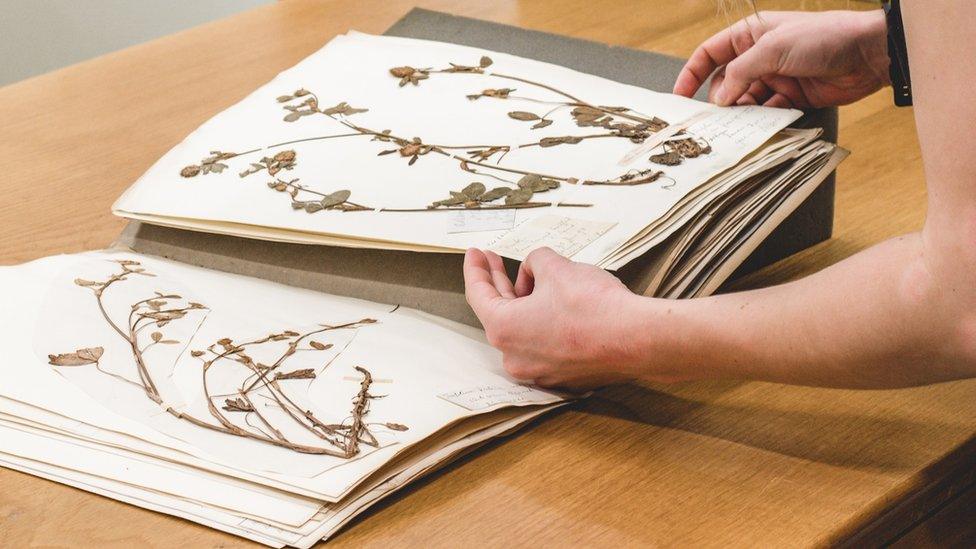

A global heritage: Oxford University's vast collection of dried plants

A million plants from every corner of the globe are tucked away inside the cabinets that line the walls.

It's a scientific collection that goes back centuries, gathered by the likes of Carl Linnaeus, the "father of taxonomy", and Charles Darwin.

They could have had no inkling that pressed, dried collections of plants would have modern uses in assessing extinction risks.

Estimates suggest one in five of the world's plant species is threatened.

Collections of pressed, dried plants are an important "living" resource, say scientists.

"People think of Herbaria as being dead, old plants and not relevant," says Kathy Willis, Professor of Biodiversity at the University of Oxford.

"It's living in the sense that the information it has is as relevant, if not more relevant, to society presently than it was in the past."

The rare giant flower, Rafflesia arnoldii, is nearing extinction

A wealth of botanical treasures can be found at the Oxford University Herbaria, from the bark and seeds of rare African trees to plants collected at the height of the Irish potato famine.

Some are mounted on medieval wallpaper; others bear the signature of famous plant collectors and scientists. Each specimen has a story to tell; speaking not just of history but of science.

As permanent scientific records of where plants have existed on the planet at a specific time, they can be used to investigate and record plant evolution and diversity.

More stories you might like to read:

The UK is a powerhouse where Herbaria are concerned, holding about 20 million of the 300 million specimens worldwide.

However, the collections are largely tucked away in cupboards, rather than digitised and available to all.

Brown paper and string

This means anyone wanting to see them has to request permission to view the collections - or ask for them to be sent out in the post.

"They still wrap them up in brown paper with string and post them," says Prof Willis, former director of science at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. "It's extraordinary. The postal bill at Kew for doing that was around £60,000 a year."

Dried plant specimens have been collected for centuries across the planet

A recent fire at Brazil's oldest historical and scientific museum has focussed attention on the risks of scientific collections being lost.

Much of the National Museum's archive of 20 million items was destroyed, causing an "incalculable" loss to Brazilian science, history and culture.

While it is impossible to put a price on unique specimens collected hundreds of years ago, the replacement value of Oxford's Herbaria alone has been estimated at at least £48 million.

Yet, while the idea of a digital Herbaria containing all the plant specimens held in the UK has been floated, there is limited funding for such work. Prof Willis says the idea has to be looked at again.

"We've got these incredible resources, but they're under huge threat as well, because you only need one fire - as happened in South America," she says.

"If you think about dried plants in dried paper in wooden cupboards - the whole lot could go up so easily."

Science from a skip

Dr Sandy Hetherington based his entire PhD thesis on fossil plant specimens that were almost lost.

"The specimens were rescued from the skip before my time in the department," he says.

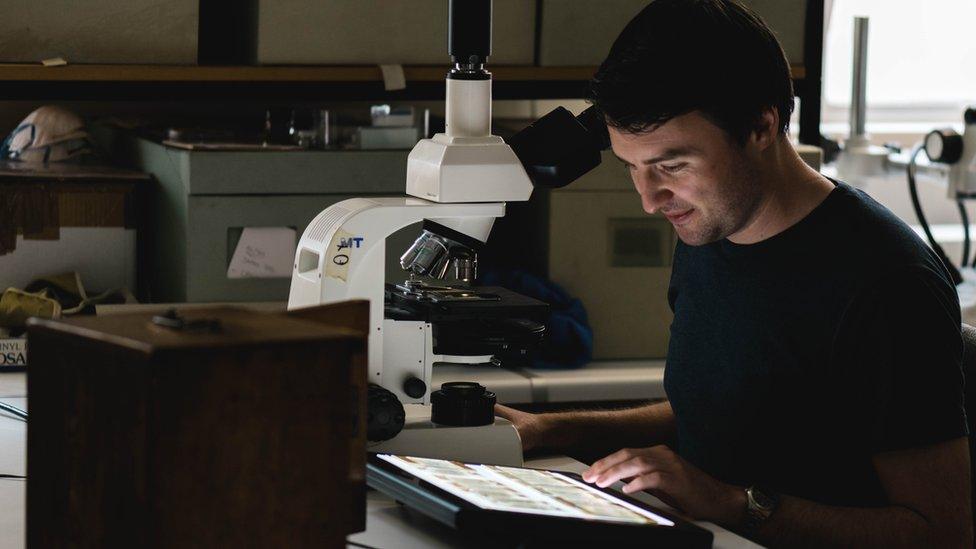

Dr Sandy Hetherington of the University of Oxford examines historic slides

Originally collected at the end of the 19th century from the Yorkshire and Lancashire coal fields, the specimens, external were subsequently digitised.

The evolutionary biologist re-examined the 300-million-year-old fossil plants trapped inside bits of coal, and discovered, external primordial root cells frozen in time.

He says the UK contains an amazing collection of fossil plants that the public are largely unaware of.

"This is a real shame as especially the fossils of carboniferous fossil forests have particular cultural significance as it was these plants which led to the formation of the UK coal deposits that fuelled the industrial revolution."

Plants such as this rare orchid are under threat from poaching

Plants are vital for life on Earth, underpinning natural processes and supplying food, medicines and fuels.

Prof George Ratcliffe, head of the department of Plant Sciences said the Herbaria are a distinctive feature of plant biology at Oxford and the collections provide a major resource for contemporary scientific investigation.

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.