Himalayan and other Asian glaciers put the brakes on

- Published

Amaury Dehecq: "Knowing ice-flow speed allows us to better estimate glacier melt"

The glaciers that flank the Himalayas and other high mountains in Asia are moving slower over time.

Scientists have analysed nearly 20 years of satellite images to come to this conclusion.

They show that the ice streams which have decelerated the most are the ones that have also thinned the most.

The research has implications for the 800 million people in the region for whom the predictable meltwater from these glaciers is a key resource.

The study is being presented at this week's American Geophysical Union (AGU) meeting, external in Washington DC - the world's largest annual gathering of Earth and space scientists.

How was the research done?

Led by the US space agency (Nasa), the assessment draws on one million pairs of pictures acquired by the Landsat-7 spacecraft, external between 2000 and 2017.

Automated software was used to track surface features on glaciers in 11 areas of High Mountain Asia, from Pamir and Hindu Kush in the West, to Nyainqêntanglha and inner Tibet and China in the East.

As the markers were observed to shift downslope, they revealed the changing speed of the ice streams.

The research team, headed by Dr Amaury Dehecq from Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, says nine of the surveyed regions show a sustained slowdown during the study period.

Nyainqêntanglha, for example, has seen a 37% reduction in speed per decade. For Spiti Lahaul, it is 34% - equivalent to about -5m/year per decade. These are glaciers that would normally move at tens of metres per year.

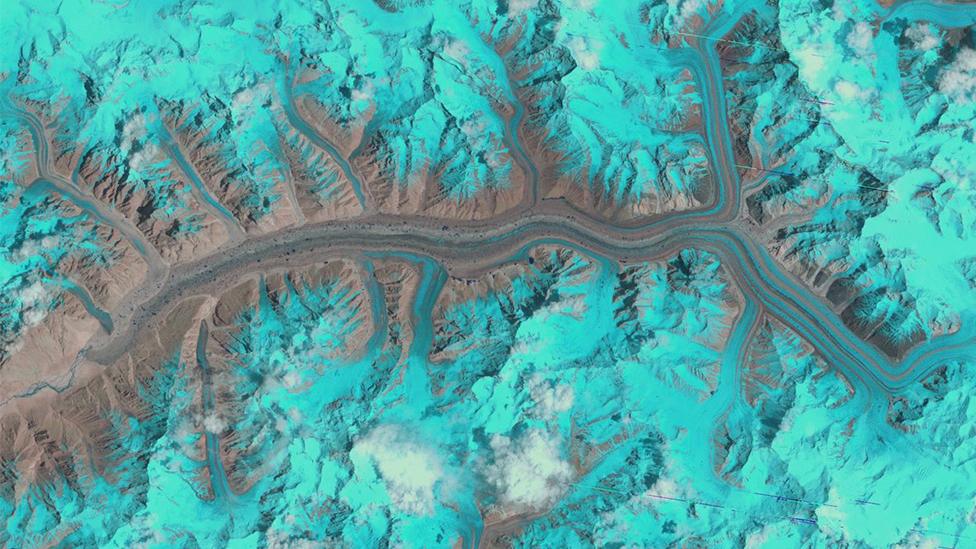

Landsat has built multi-decade records of glacier behaviour in Asia

What was the key finding?

Perhaps the major revelation is that the reduction in velocity is strongly correlated with thinning. Nyainqêntanglha's glaciers have been thinning on average by about 60cm a year; Spiti Lahaul's glaciers are losing thickness at a rate of roughly 40cm a year.

"The reason a glacier flows is because of gravity," explained Dr Dehecq. "Under its weight, the glacier slides across its bed and deforms, but as it thins it finds it more difficult to slide and deform; it's kind of intuitive.

"But until now there had been some debate as to whether other factors were influencing speed, such as the lubrication of the bed as a result of increased meltwater getting under the glacier. Well, we show thinning is actually the dominant factor," he told BBC News.

Are some glaciers getting faster?

The slowdown trend is strongest in the south and southeast of High Mountain Asia; it is less pronounced in the West.

Regions like the Karakorum in Pakistan, and Kunlun just across the border in Tibet/China, have actually shown a slight thickening over time and a marginal speed-up as a consequence.

"That's the influence of different climatic conditions," said co-author Dr Noel Gourmelen from Edinburgh University, UK. "Precipitation in the East is affected by the Asian monsoon and in the West and North-West, it is delivered by westerlies; although it's not exactly clear why the Karakorum has been gaining mass."

Galcier meltwaters ensure south Asia has a consistent supply of water, even in drought

Why is this research important?

The meltwater that flows from the 90,000 glaciers in High Mountain Asia is critical to the lives and livelihoods of the people downstream. But the significance goes much wider, because the snow and ice stored "in the freezer" at high altitude would otherwise push up global sea levels if it all melted and ran into the ocean. That is why scientists need to understand how the glaciers will respond in an ever-warming world.

This study, which has also been published in the journal Nature Geoscience, external, has described an important dynamic that will moderate how much ice is transported down mountains to the elevations where it can melt.

Computer models that try to project the future resilience of the glaciers in what they call Earth's "third pole" must now take account of this behaviour.

Dr Hamish Pritchard from the British Antarctic Survey also studies these glaciers. He said their contribution to rivers across the region was small in the average year, but significantly heightened during years of drought.

"My research shows that when the summer rains fail, glacier melt comes to dominate water inputs to many catchments in India, Nepal, Pakistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Without this water supply more crops would fail, substantially less hydropower would be generated and more people would be forced to migrate," he told BBC News.

"These rivers that flow down from the mountains pass through many communities and across national borders, so when supplies are low, tensions between neighbouring communities and countries would likely increase.

"Studies show that this tension could lead to conflict, with implications far beyond South and Central Asia.

"The key role of these glaciers then is as a buffer against the worst effects of drought, and so the loss of glacier ice can be seen as a threat to the future stability of the region."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external