Amount of deep life on Earth quantified

- Published

Bob Hazen: "It opens the window to lifeforms we may not even be able to imagine"

Scientists have estimated the total amount of life on Earth that exists below ground - and it is vast.

You would need a microscope to see this subterranean biosphere, however.

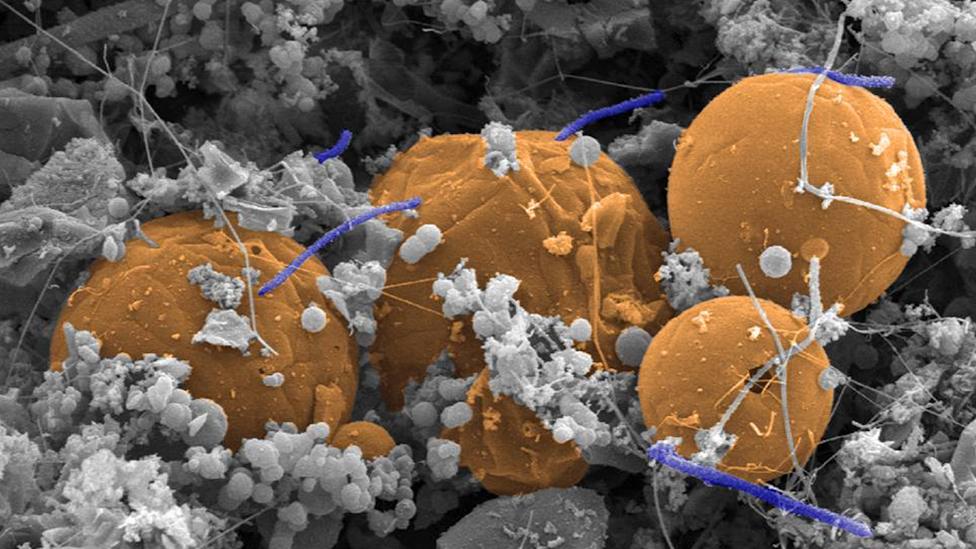

It is made up mostly of microbes, such as bacteria and their evolutionary cousins, the archaea.

Nonetheless, it represents a lot of carbon - about 15 to 23 billion tonnes of it. That is hundreds of times more carbon than is woven into all the humans on the planet.

"Something like 70% of the total number of microbes on Earth are below our feet," said Karen Lloyd from the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, US.

"So, this changes our perception of where we find life on Earth, from mostly on the surface in things like trees and whales and dolphins, to most of it actually being underground," she told BBC News.

Prof Lloyd is part of the Deep Carbon Observatory (DCO) project, a near-decade long effort to identify how the ubiquitous element is cycled through the Earth system. The consortium is reporting its latest discoveries here at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) annual Fall Meeting in Washington DC, external.

The organisms individually may be tiny but collectively they represent a huge amount of carbon

How did they work out the scale of life?

The mass numbers it quotes can only be a rough estimate.

They are derived from multiple studies that have dug or drilled several kilometres into the crust, both on the continents and at sea.

Scientists will routinely pull up rock and other sediment samples and count the number living cells in a given volume.

The DCO teams have taken these inventories and used models to construct a broader picture of Earth's total biomass.

"Even though these sample sites are but pinpricks around the planet, we've managed now to look at enough different environments that we can produce reasonable values for the total amount of carbon locked up in lifeforms," said Rick Colwell from Oregon State University.

Scientists are even sampling life far under the seabed

What's the importance of carbon?

The DCO consortium reckons the deep biosphere constitutes about 2 to 2.3 billion cubic km. That is almost twice the volume of all the oceans.

Bacteria and archaea (microbes with no membrane-bound nucleus) dominate. But there are also eukarya (microbes or multicellular organisms with cells that contain a nucleus as well as membrane-bound organelles) down there, such as the tiny nematode worms discovered in rock cracks at the bottom of deep mines.

Science has barely begun to describe this microscopic menagerie.

Scientists collect ancient water samples 1.3 km underground to test for their microbial content

Deep microbes are often quite different to seemingly related species that thrive at the surface, with life cycles that operate on near-geologic timescales. And because these underground organisms persist far from sunlight they must exploit chemosynthesis - as opposed to photosynthesis - to nourish themselves. The minerals in the rocks around them are their larder.

The role all these organisms play in shifting carbon about the Earth is profound, according to the DCO's executive director, Bob Hazen.

"You cannot understand carbon on Earth without understanding the diversity and influence of life. Cells turn over carbon - they take carbon in, they breathe it out. They do amazing things to transform their local environments," he explained.

"Although the total amount of carbon in other sources is much, much larger than in life, life has a disproportionate affect on Earth's carbon cycle."

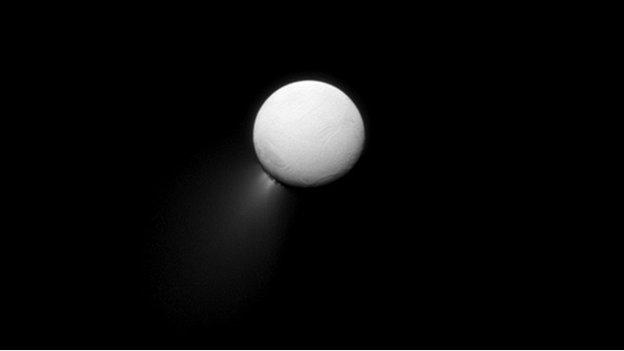

Somewhere out there? Could other planets and moons have subterranean ecosystems?

What are the implications of this research?

Another aspect of the research is what is says about the absolute limits of life on Earth in terms of temperature, pressure, and the availability of energy.

"The current known upper-limit for life is 122 degrees Celsius, which happens to be the temperature of sterilisation equipment we typically use in labs," said Dr Lloyd.

"But there's no-one I know who thinks that's the theoretical limit. For example, we know some of the problems associated with high temperatures, such as the disordering of lipids and membranes, is at least partially compensated by higher pressures. Which means it's possible we could find even higher temperature organisms the deeper we go down."

And this has clear implications for the possibility that life exists somewhere else in the Solar System, adds Prof Colwell.

"I think it's probably reasonable to assume that the subsurface of other planets and their moons are habitable, especially since we've seen here on Earth that organisms can function far away from sunlight using the energy provided directly from the rocks deep underground," he told BBC News.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published2 March 2017

- Published13 February 2016

- Published18 December 2014