Nasa's IceSat space laser makes height maps of Earth

- Published

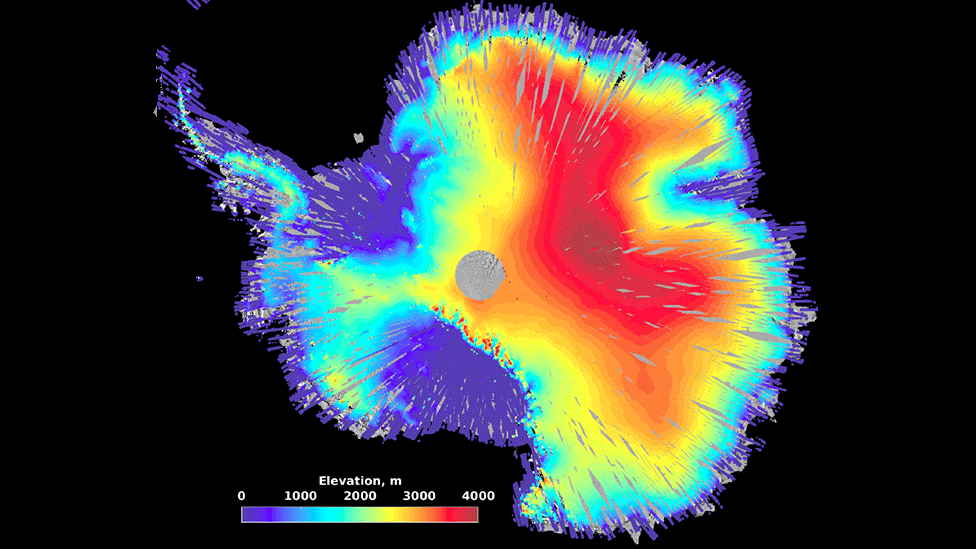

A key focus for IceSat will be looking for changes in elevation over Antarctica and Greenland

One of the most powerful Earth observation tools ever put in orbit is now gathering data about the planet.

IceSat-2, external was launched just under three months ago to measure the shape of the ice sheets to a precision of 2cm.

But the Nasa spacecraft's laser instrument is also now returning a whole raft of other information.

It is mapping the height of the land, of rivers, lakes, forests; and in a remarkable demonstration of capability - even the depth of the seafloor.

"We can see down to 30m in really clear waters," said Lori Magruder, the science team leader on the IceSat mission. "We saw one IceSat track just recently that covers 300km in the Caribbean and you see the ocean floor the entire way," the University of Texas researcher told BBC News.

She was speaking here at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting, external - the largest annual gathering of Earth and space scientists.

Other stories from the AGU meeting you might like:

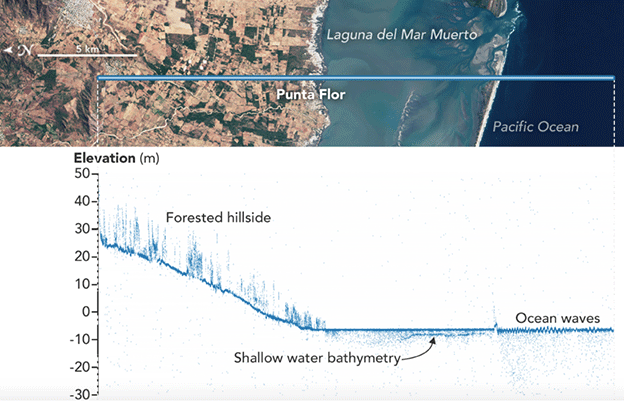

The blue line is the laser's track across the scene (photo above) and the heights it detects (below)

Nasa has been showcasing the early data from the new satellite at the AGU meeting.

IceSat-2 was sent up on 15 September. It carries just the single instrument - a half-tonne green laser that fires about 10,000 pulses of light every second.

Each of those shots goes down to the Earth and bounces back up on a timescale of about 3.3 milliseconds. The exact time equates to the height of the reflecting surface.

Scientists will be using this optical "tape measure" to look in particular for the elevation changes in Antarctica and Greenland that might indicate melting.

Lori Magruder: "Some of the features we've been able to see have been really quite surprising"

And the great advantage of the new laser system is that it can detect behaviour in areas that have been beyond the vision of previous satellites.

"We're resolving every valley in the mountains," said team-member Ben Smith from the University of Washington, Seattle.

"These have been really difficult targets for altimeters in the past, which have often used radar instead of lasers and they tend to show you just a big lump where the mountains are. But we can see very steeply sloping surfaces; we can see valley glaciers; we'll be able to make out very small details."

With just a few weeks of data, IceSat is starting to build ice sheet maps

As its name suggests, IceSat-2 is a follow-on mission. It is a successor and upgrade to the IceSat-1 mission that flew from 2003 to 2009.

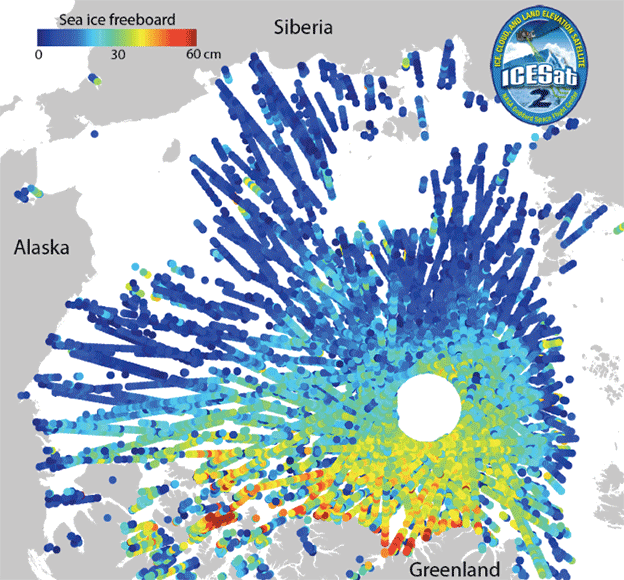

The old spacecraft helped pioneer the assessment of sea-ice volume in the Arctic. This is a measurement that involves sensing the difference in height between the top of the floating floes and the surface of the ocean.

The offset - known as the freeboard - allows researchers to calculate that part of the ice submerged below water. But it requires the satellite to find the cracks in floes where the measurement can be made - and this has just become a whole lot easier thanks to the new laser's horizontal footprint of about 25-30m.

"Eighty percent of the cracks are less than 50m across, so the resolution of IceSat is very important," said Ron Kwok from Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California.

Heights are calculated from just 150 photons, or particles, of reflected light, but even from just this small number, IceSat-2 is able to produce an elevation number to an accuracy of a little over 2cm. The AGU meeting was shown some of the first efforts to build a sea-ice thickness map for the Arctic.

Early days, but IceSat is gathering data that will enable measurements of Arctic sea-ice thickness

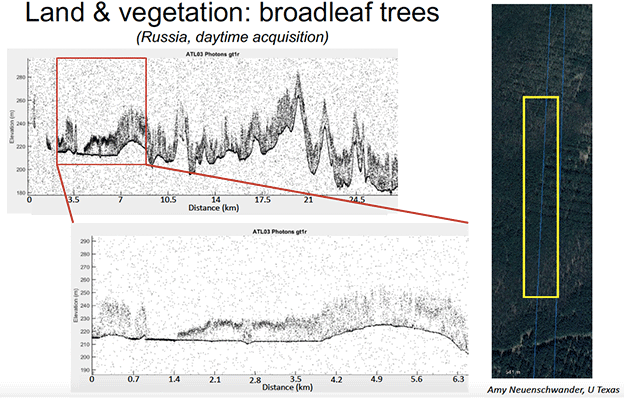

Sample data was also presented of forested areas. The laser sees the tree canopy and the ground underneath, which will enable new assessments to be made of the amount of carbon stored in vegetation across the Earth.

But it is probably the bathymetry information that grabs the immediate headlines.

It was suspected that the laser might be able to measure the depth of shallow coastal waters, but not this well.

Already a project is being developed to use IceSat to map the near-shores of about 100 small islands in the Pacific.

"You need to know the bathymetry to understand how waves will move on to the reefs and atolls," explained Sinéad Farrell from the University of Maryland. "If you have storm surges, for example, you need to know those depths to accurately model what those waves will do; and currently there's almost no bathymetry data at all for these islands."

Some of the laser light reflects off the canopy and some off the ground below

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external