Chang'e-4: Chinese rover now exploring Moon

- Published

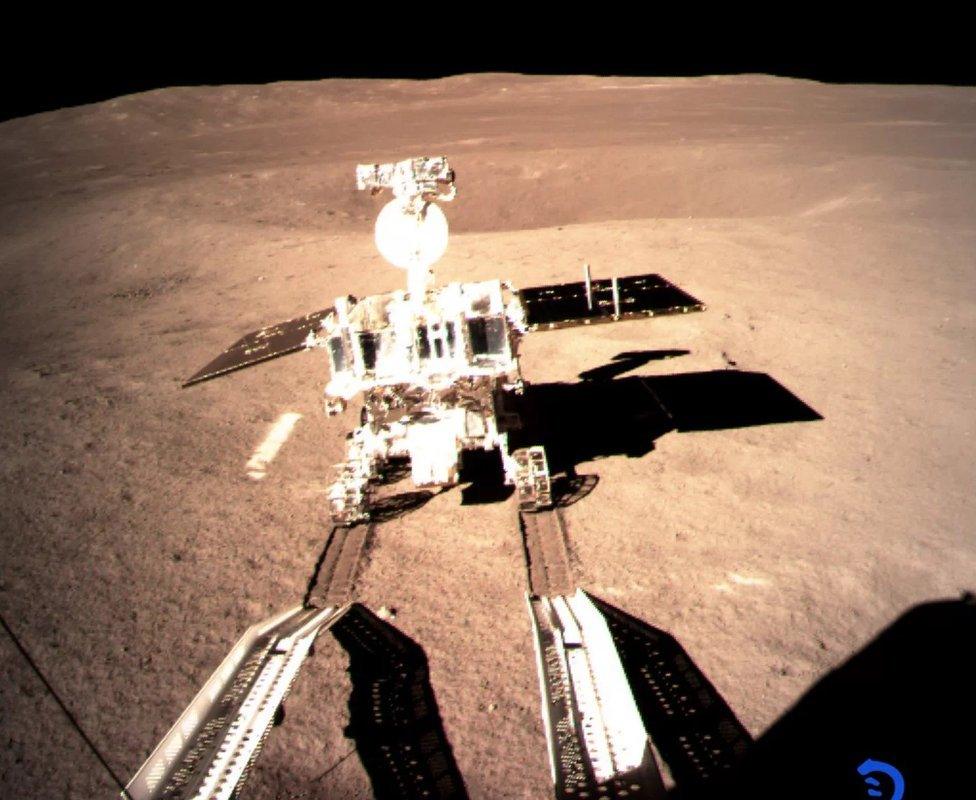

An image of the rover rolling off the lander

A Chinese robotic rover has got its wheels dirty after rolling off its landing craft and onto the lunar soil.

The Chang'e-4 spacecraft touched down on the far side of the Moon at 10:26 Beijing time (02:26 GMT) on Thursday.

Lunar exploration chief Wu Weiren echoed Neil Armstrong's famous quote, telling state media the event marked a "huge stride" for China.

The rover and lander are carrying instruments to analyse the unexplored region's geology.

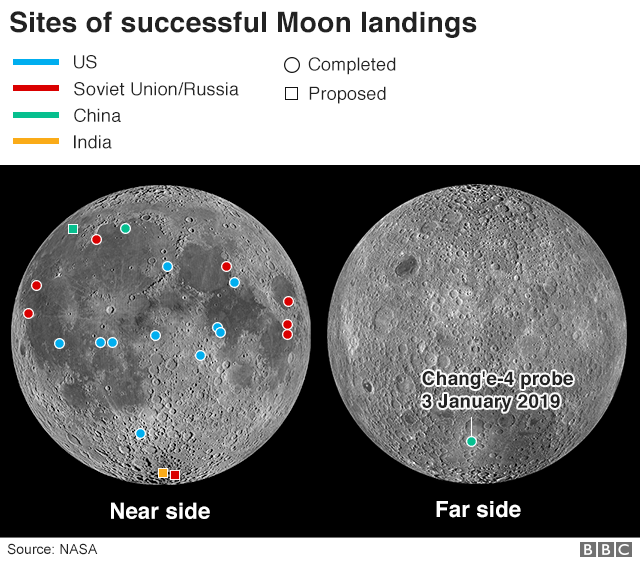

It represents the first ever such attempt and landing on the far side of the Moon, which has distinct characteristics to the near side we can see from Earth.

According to the Guardian newspaper, external, Weiren told the state broadcaster CCTV: "The separation of Chang'e 4's rover was smooth and perfect."

"The rover rolled only a small step on to the Moon, but it represented a huge stride for the Chinese nation."

The rover touched the lunar surface at 22:22 Beijing time (14:22 GMT), about 12 hours after the landing.

The event was captured by the camera on the lander and the images were sent back to the Earth via the relay satellite "Queqiao", China's Xinhua state news agency reported., external

China has also chosen a name for the rover - Yutu 2 - following a worldwide poll to name the rover in August., external

In Chinese folklore, Yutu is the white pet rabbit of Chang'e, the moon goddess who lent her name to the Chinese lunar mission.

The number two at the end of the name acknowledges its predecessor, a Chinese rover called Yutu which touched down at Mare Imbrium on the Moon's near side in 2013.

Why is this Moon landing so significant?

Previous Moon missions have landed on the Earth-facing side, but this is the first attempt to explore the rugged far side from the surface.

Some spacecraft have crashed into the far side, either after system failures, or after they had completed their mission.

Ye Quanzhi, an astronomer at Caltech, told the BBC this was the first time China had "attempted something that other space powers have not attempted before".

Landing on the far side isn't fundamentally different to landing on the near side of the Moon. But it presents a communications challenge because there's no direct line of sight to Earth.

The far side is not visible from the Earth due to "tidal locking"

The Chang'e-4 was launched from Xichang Satellite Launch Centre in China on 7 December; it arrived in lunar orbit on 12 December.

It was then directed to lower itself toward the Moon, being careful to identify and avoid obstacles, Chinese state media say.

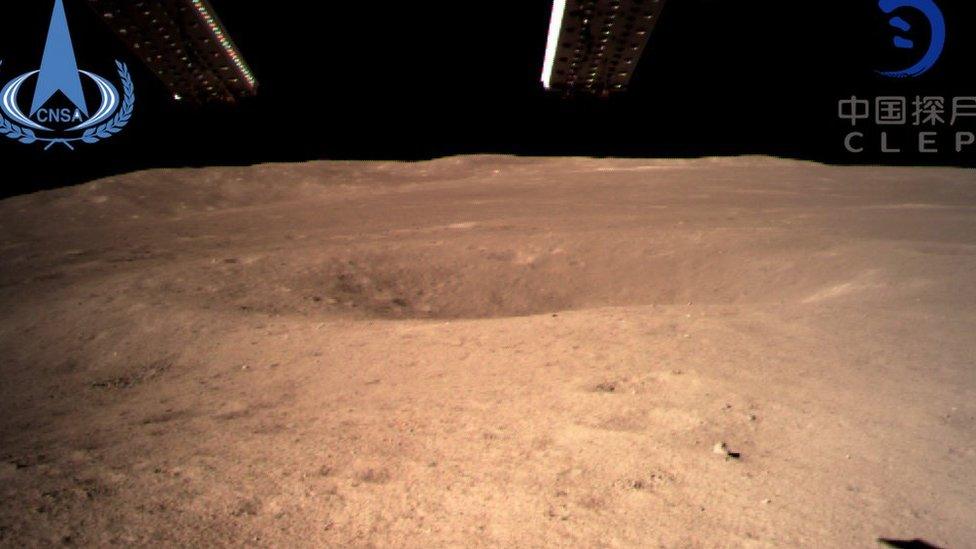

The Chang'e-4 probe is aiming to explore a place called the Von Kármán crater, located within the much larger South Pole-Aitken (SPA) Basin - thought to have been formed by a giant impact early in the Moon's history.

"This huge structure is over 2,500km (1,550 miles) in diameter and 13km deep, one of the largest impact craters in the Solar System and the largest, deepest and oldest basin on the Moon," Andrew Coates, professor of physics at UCL's Mullard Space Science Laboratory, external in Surrey, told the BBC.

The event responsible for carving out the SPA basin is thought to have been so powerful, it punched through the Moon's crust and down into the zone called the mantle. Researchers will want to train the instruments on any mantle rocks exposed by the calamity.

The science team also hopes to study parts of the sheet of melted rock that would have filled the newly formed South Pole-Aitken Basin, allowing them to identify variations in its composition., external

Another objective is to study the far-side regolith, the broken up rocks and dust that make up the surface, which will help us understand the formation of the Moon.

What else might we learn from this mission?

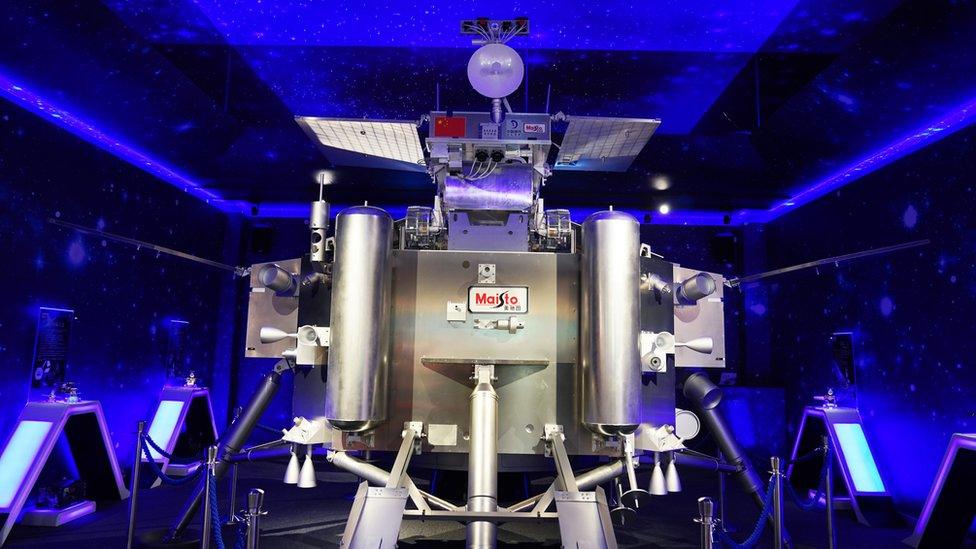

Chang'e-4's static lander is carrying two cameras; a German-built radiation experiment called LND; and a spectrometer that will perform low-frequency radio astronomy observations.

Scientists believe the far side could be an excellent place to perform low-frequency radio astronomy, because it is shielded from the radio noise of Earth.

A mock-up of the Chang'e-4 lander and rover, on display in Dongguan, China

The lander also carried a container with six live species from Earth - cotton, rapeseed, potato, fruit fly, yeast and arabidopsis (a flowering plant) - to try to form a mini biosphere.

The arabidopsis plant may produce the first flower on the Moon, Chinese state media say.

Other equipment/experiments include:

A panoramic camera

A radar to probe beneath the lunar surface

An imaging spectrometer to identify minerals

An experiment to examine the interaction of the solar wind (a stream of energised particles from the Sun) with the lunar surface

The mission is part of a larger Chinese programme of lunar exploration. The first and second Chang'e missions were designed to gather data from orbit, while the third and fourth were built for surface operations.

Chang'e-5 and 6 are sample return missions, delivering lunar rock and soil to laboratories on Earth.

Is there a 'dark side of the Moon'?

The lunar far side is sometimes referred to as the "dark side", though "dark" in this case means "unseen" rather than "lacking illumination". In fact, both the near and far sides of the Moon experience daytime and nighttime. Scientists prefer to use far side to avoid confusion.

But because of a phenomenon called "tidal locking", we see only one face of the Moon from Earth. This is because the Moon takes just as long to rotate on its own axis as it takes to complete one orbit of Earth.

The far side has a thicker, older crust that is pocked with more craters. There are also very few of the "maria" - dark basaltic "seas" created by lava flows - that are evident on the near side.

How will scientists keep track of the rover?

In an article for the US-based Planetary Society in September, external, Dr Long Xiao from the China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), said: "The challenge faced by a far side mission is communications. With no view of Earth, there is no way to establish a direct radio link."

So the landers must communicate with Earth using a relay satellite named Queqiao - or Magpie Bridge - launched by China last May.

Queqiao orbits 65,000km beyond the Moon, around a Lagrange point - a kind of gravitational parking spot in space where it will remain visible to ground stations in China and other countries such as Argentina.

What are China's plans in space?

China wants to become a leading power in space exploration, alongside the United States and Russia.

It has long harboured ambitions to send its own astronauts to the Moon.

It will also begin building a new space station next year, with the hope it will be operating by 2022.

A full-size model of the Tianhe core module of China's space station

Commentators have focused on the secrecy surrounding this launch and landing. Details of the Chang'e 4 landing attempt were sketchy before the official announcement it had been a success.

The careful news management echoes the way the Soviet Union handled its space missions in the latter half of the 20th Century.

The far side of the Moon is more rugged than the near side, so the Chang'e-4 landing was more risky and complex. Scientists targeted a very flat area, but coming down on a sharp outcrop would have spelled instant failure for the mission.

Caution by the Chinese authorities could have been behind the limited flow of news, which saw audiences searching for unofficial feeds of the launch on the social network Weibo due to the lack of coverage on state television.

But Ye Quanzhi said China had made efforts to be more open.

"They live-streamed the launch of Chang'e 2 and 3, as well as the landing of Chang'e 3. PR skills take time to develop but I think China will get there," he said.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external