Blue tooth reveals unknown female artist from medieval times

- Published

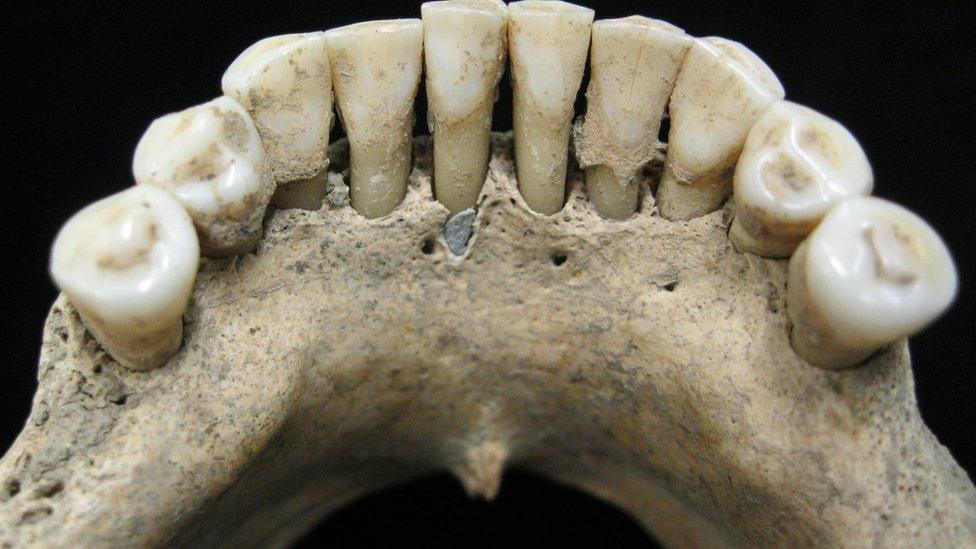

A lapis lazuli fragment trapped in the lower jaw of the medieval woman

The weird habit of licking the end of a paintbrush has revealed new evidence about the life of an artist more than 900 years after her death.

Scientists found tiny blue paint flecks had accumulated on the teeth of a medieval German nun.

The particles of the rare lapis lazuli pigment likely collected as she touched the end of her brush with her tongue.

The researchers say it shows women were more involved in the illumination of sacred texts than previously thought.

The team had initially been investigating health and diets in the Middle Ages. They set out to examine the bones of corpses at a medieval monastery in Dalheim, Germany.

The scientists analysed dental calculus - essentially dental plaque that has become fossilised on your teeth during your lifetime.

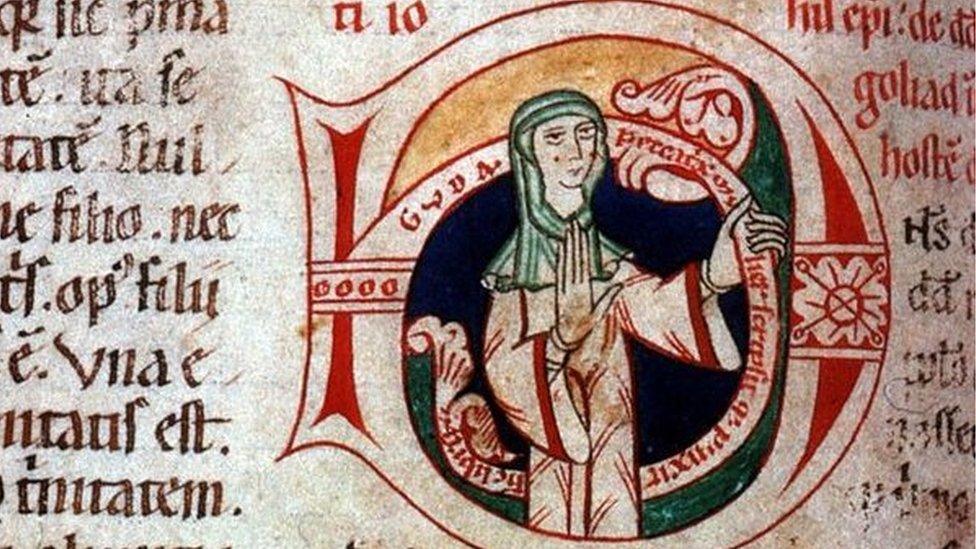

Guda, a twelfth century nun and illuminator. Credited as one of the first women in Europe to create a signed self-portrait, she holds a Latin inscription reading “Guda, peccatrix mulier scripsit et pinxit hunc librum,” translated as “Guda, a sinful woman, wrote and painted this book.”

When they examined the teeth of one subject, called B78, it ultimately revealed far more than what she had eaten.

According to radiocarbon dating, the woman had lived between 997 and 1162AD and was between 45-60 years old when she died. According to the authors, the woman was average in almost every aspect - except for what was stuck to her teeth.

When the researchers dissolved samples of her dental calculus, they couldn't believe their eyes. Hundreds of tiny blue particles became visible.

"Dental calculus is really cool, it is the only part of your body that fossilises while you are still alive," senior author Dr Christina Warriner, from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany, told BBC News.

"During this process it incorporates all sorts of debris from your life, so bits of food become trapped, it ends up being a bit of a time capsule of your life."

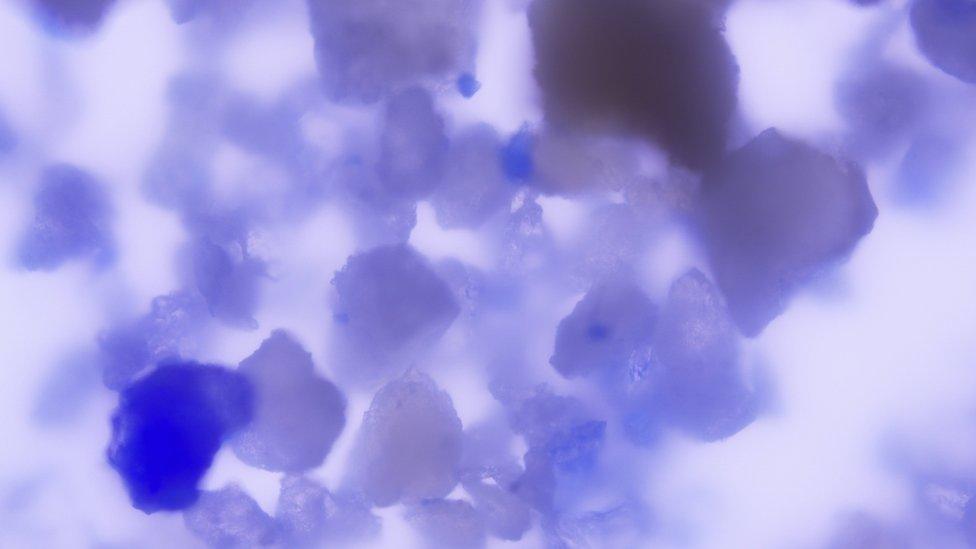

"We found starch granules and pollen but what we also saw was this bright, bright blue - and not just one or two little flecks of mineral, but hundreds of them. We had never seen that before."

A magnified view of lapis lazuli particles embedded within medieval dental calculus.

It took some major scientific sleuthing to work out what the particles were made of.

Eventually, the scientists realised they were dealing with lapis lazuli, a rare and valuable pigment, that originated from a mountain in Afghanistan.

The lapis would be ground into a powder and mixed to make ultramarine - a vivid blue, so expensive that artists like Michelangelo weren't able to afford it.

It was used in Medieval Europe to decorate only the most valuable religious manuscripts.

So how did this rarest of artistic materials end up in the teeth of a rural German religious woman?

"Based on the distribution of the pigment in her mouth, we concluded that the most likely scenario was that she was herself painting with the pigment and licking the end of the brush while painting," says co-first author Monica Tromp, also from the Max Planck Institute in Jena.

The foundations of the church associated with a medieval women’s religious community at Dalheim, Germany

The researchers say that only scribes and painters of exceptional skill would have been entrusted with the use of this highly prized pigment.

The discovery indicates that women were playing a far more significant role in the writing and illustration of manuscripts at this time than has previously been recognised.

While there were women's monasteries in this period, it had been believed that less than 1% of books could be attributed to them before the 12th century.

Often women didn't sign their names to books as a sign of humility, but the authors also believe there was a strong male bias at the time, and women were essentially rendered invisible. The authors say that their findings are helping to set the record straight.

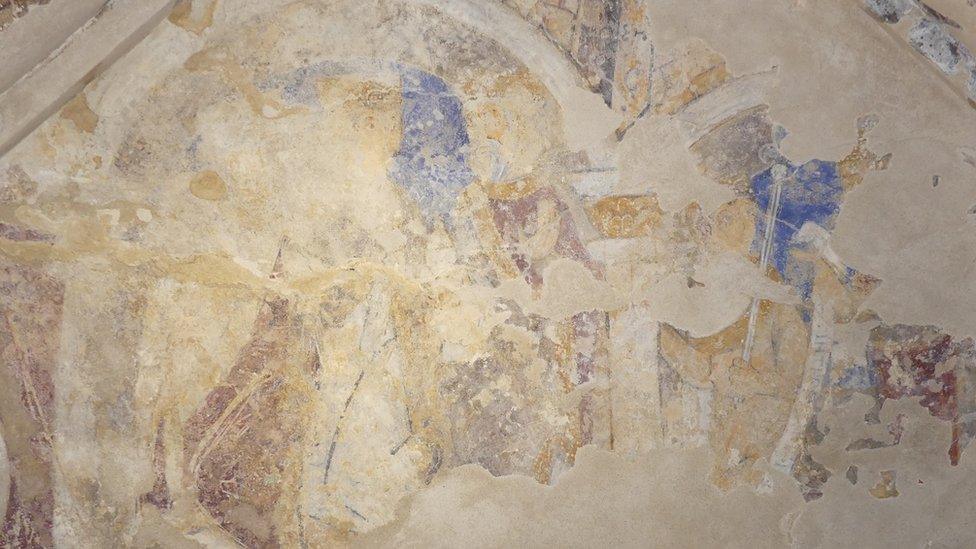

These 12th century frescoes in Cormac's chapel at the Rock of Cashel in Ireland were painted with pigments derived from lapis lazuli

"She lived at Dalheim, you can still see the ruins of the women's community, but there is no art, no books, just a fragment of a comb, there's only a handful of references in texts," said Dr Warriner.

"It was written out of history, but now we've discovered another place that women were engaged in artistic production that we had no idea about."

The researchers are keen to develop the technique, believing that many other artists who worked with a variety of mineral pigments from the period could be identified.

"I think this would be an incredible opportunity to give identity back to these people, we have lost all individuality from them."

The study has been published, external in the journal Science Advances.