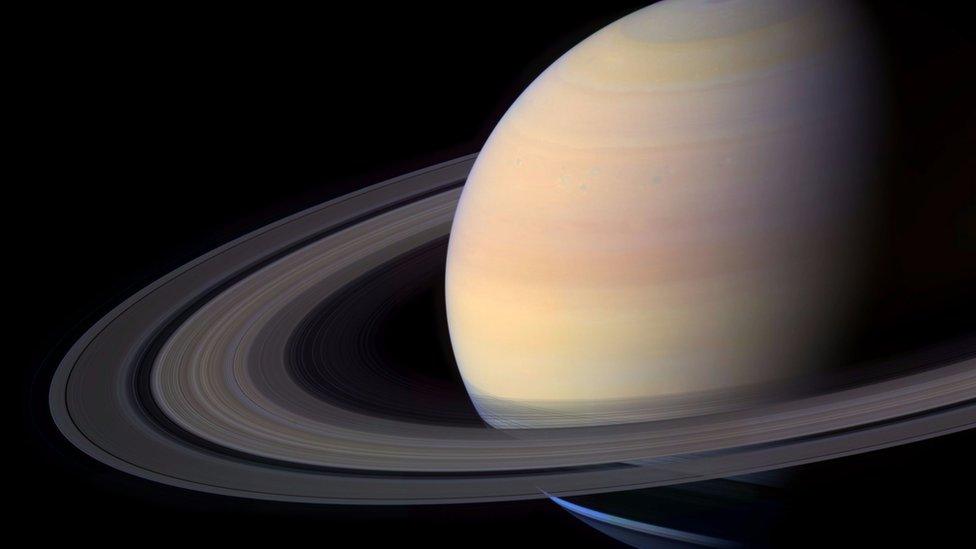

Saturn's spectacular rings are 'very young'

- Published

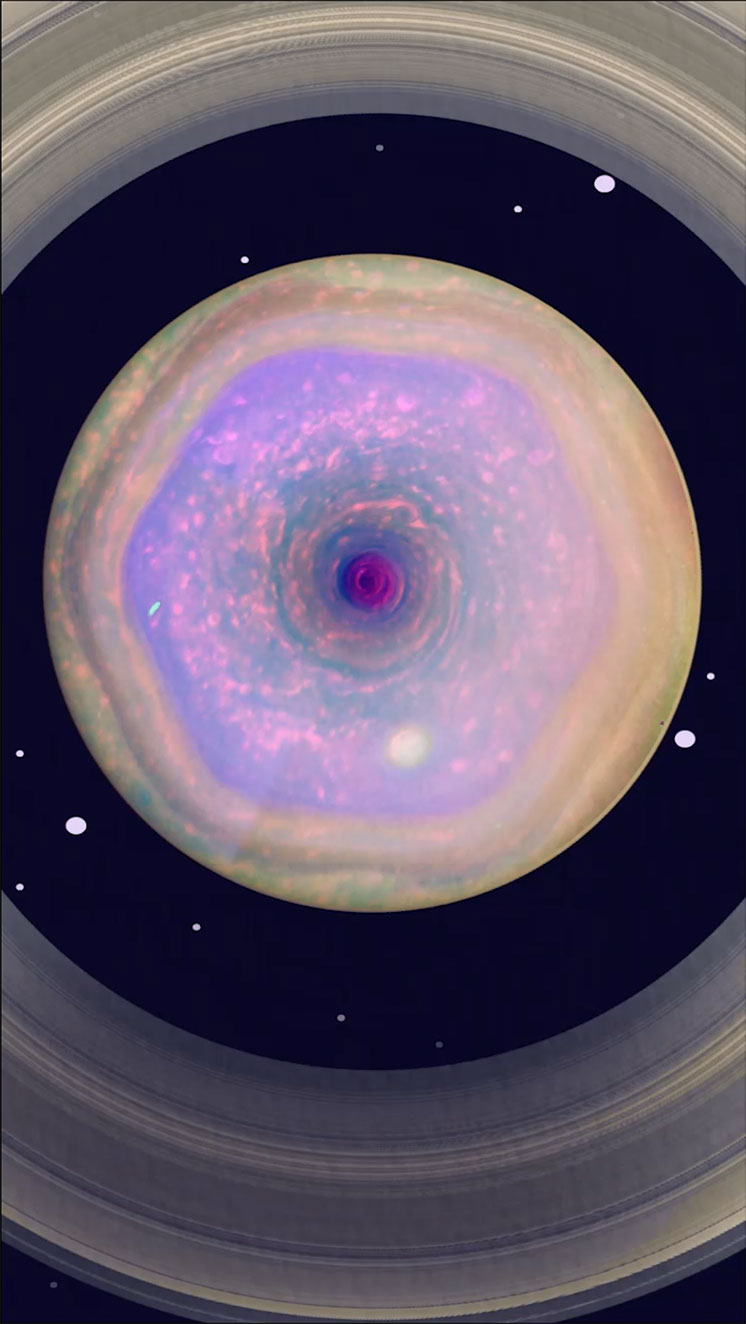

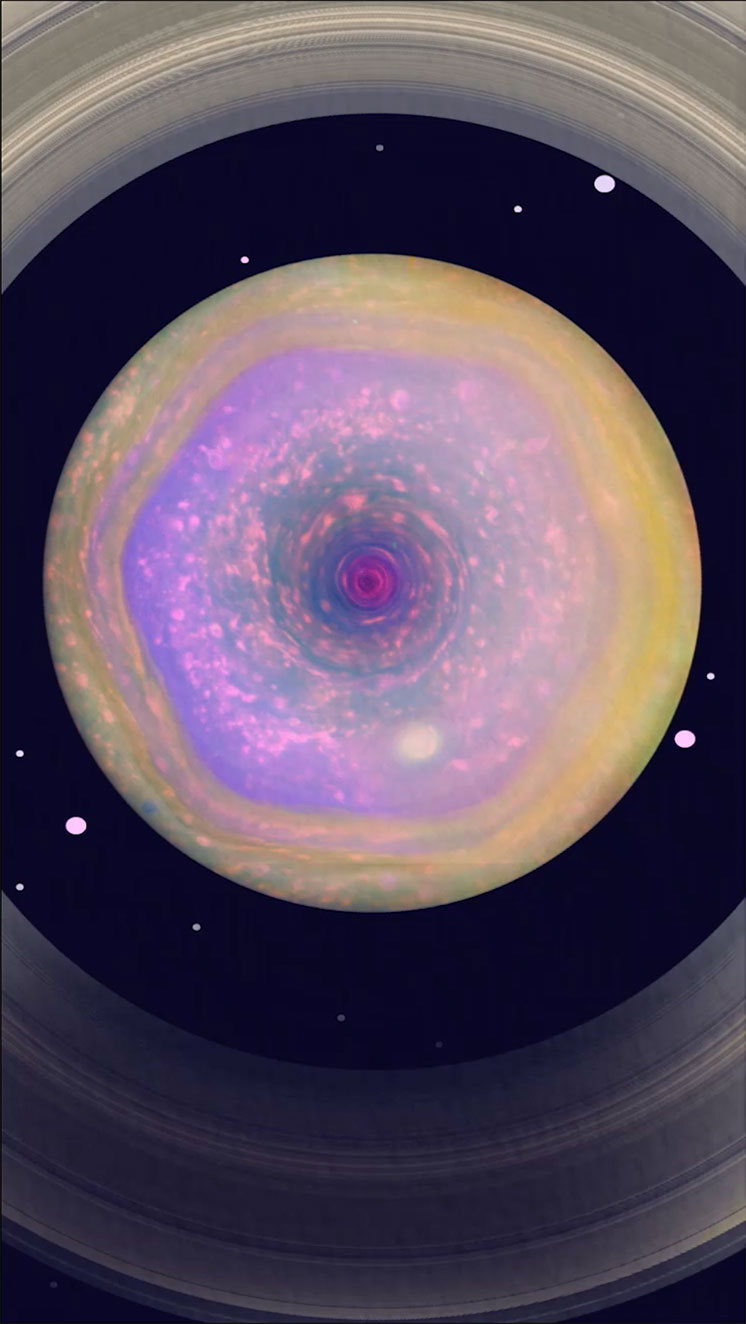

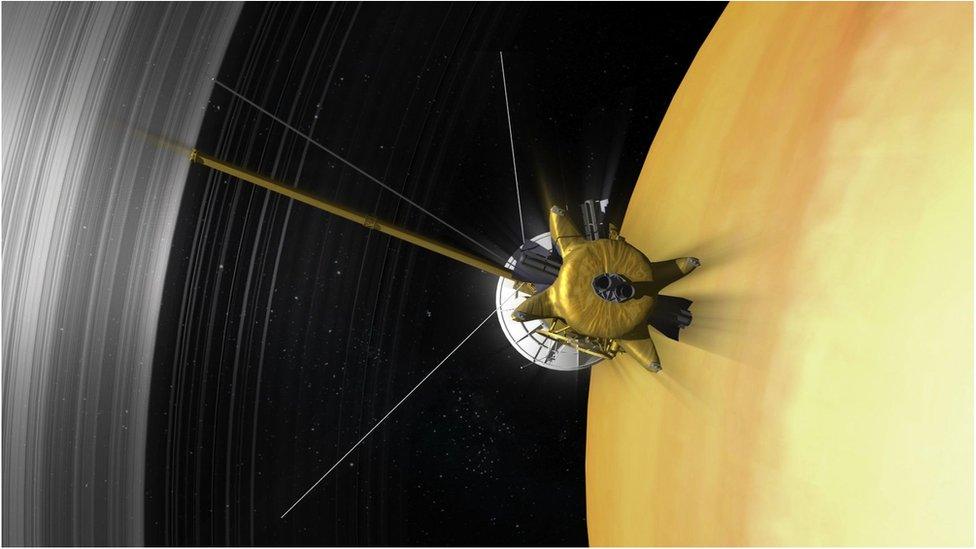

The end phases of the mission should yield new information about Saturn's interior

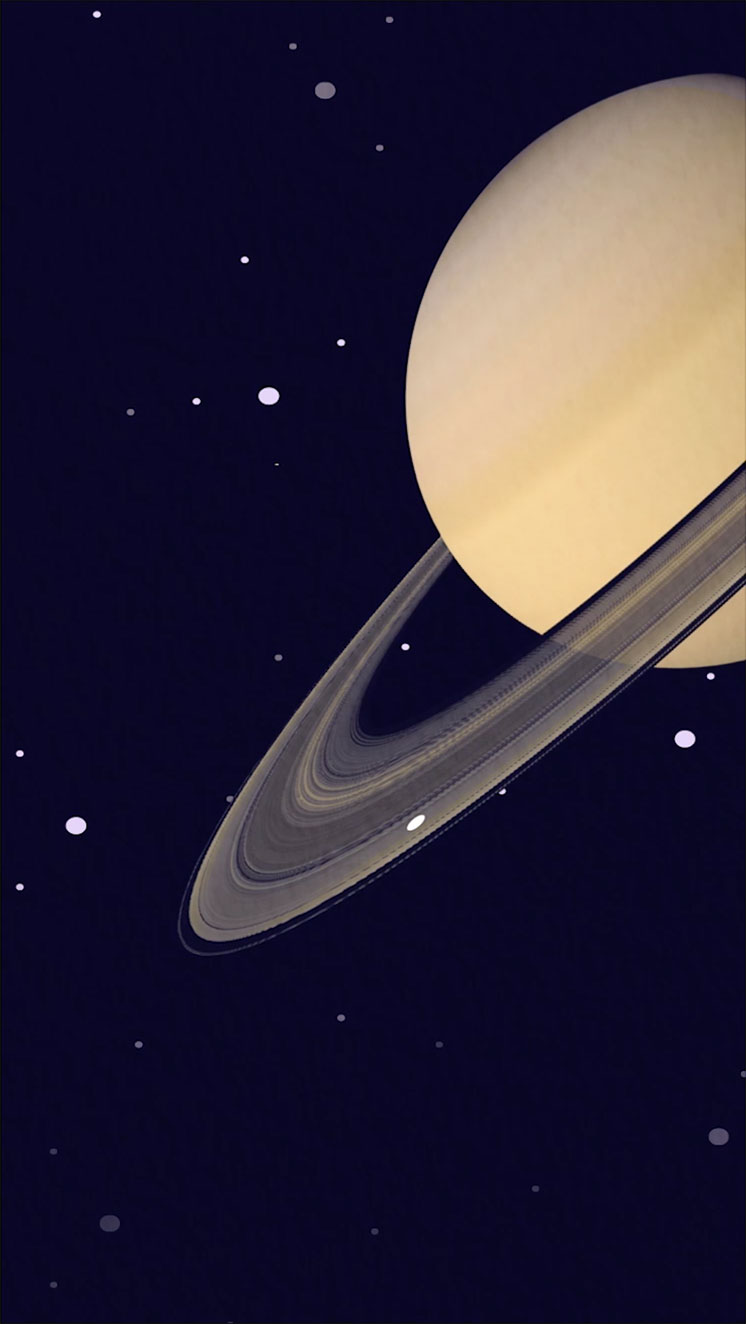

We're looking at Saturn at a very special time in the history of the Solar System, according to scientists.

They've confirmed the planet's iconic rings are very young - no more than 100 million years old, when dinosaurs still walked the Earth.

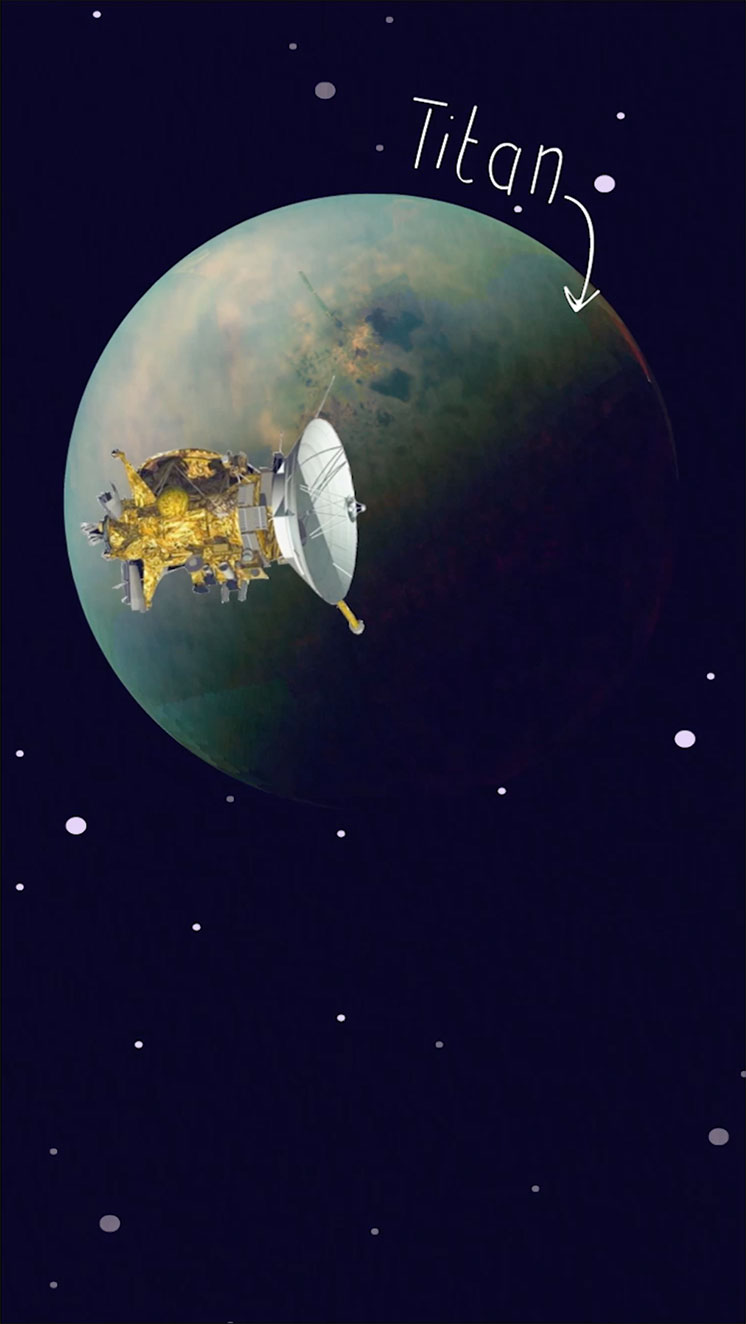

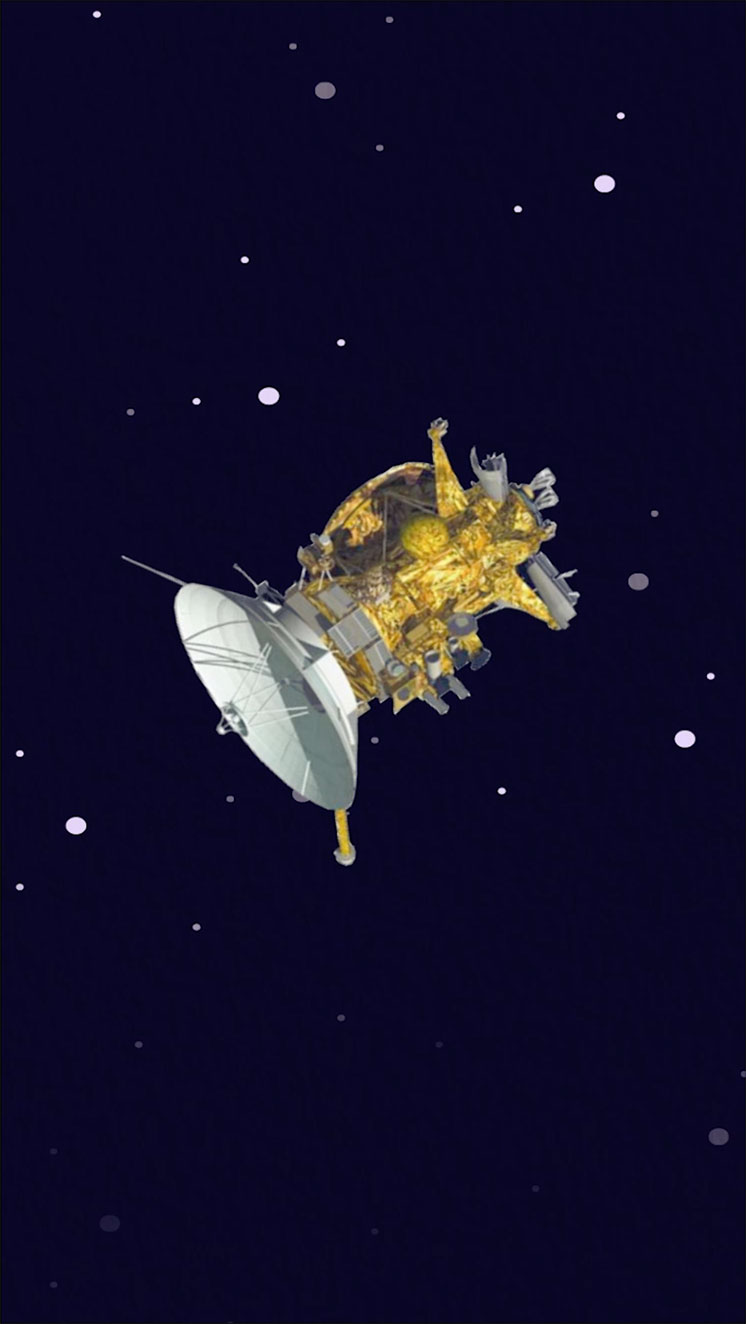

The insight comes from the final measurements acquired by the American Cassini probe.

The satellite sent back its last data just before diving to destruction in the giant world's atmosphere in 2017.

"Previous estimates of the age of Saturn's rings required a lot of modelling and were far more uncertain. But we now have direct measurements that allows us to constrain the age very well," Luciano Iess from Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, told BBC News.

The professor's team has published an account of its work with Cassini in Science magazine, external.

Cassini: A mission of 'astonishing discovery'

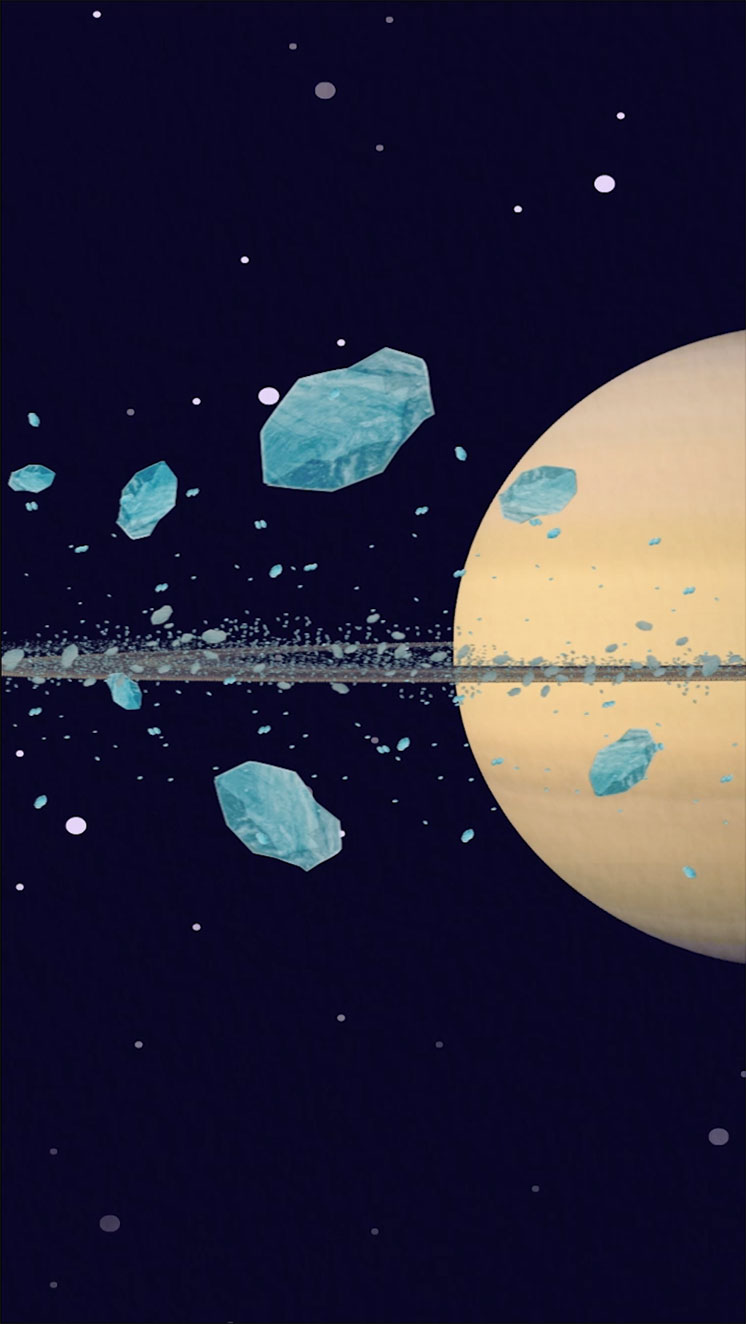

There has long been a debate about the age of Saturn's rings. Some had argued these gorgeous loops of icy particles most likely formed along with the planet itself, some 4.5 billion years ago.

Others had suggested they were a recent phenomenon - perhaps the crushed up remains of a moon or a passing comet that was involved in a collision.

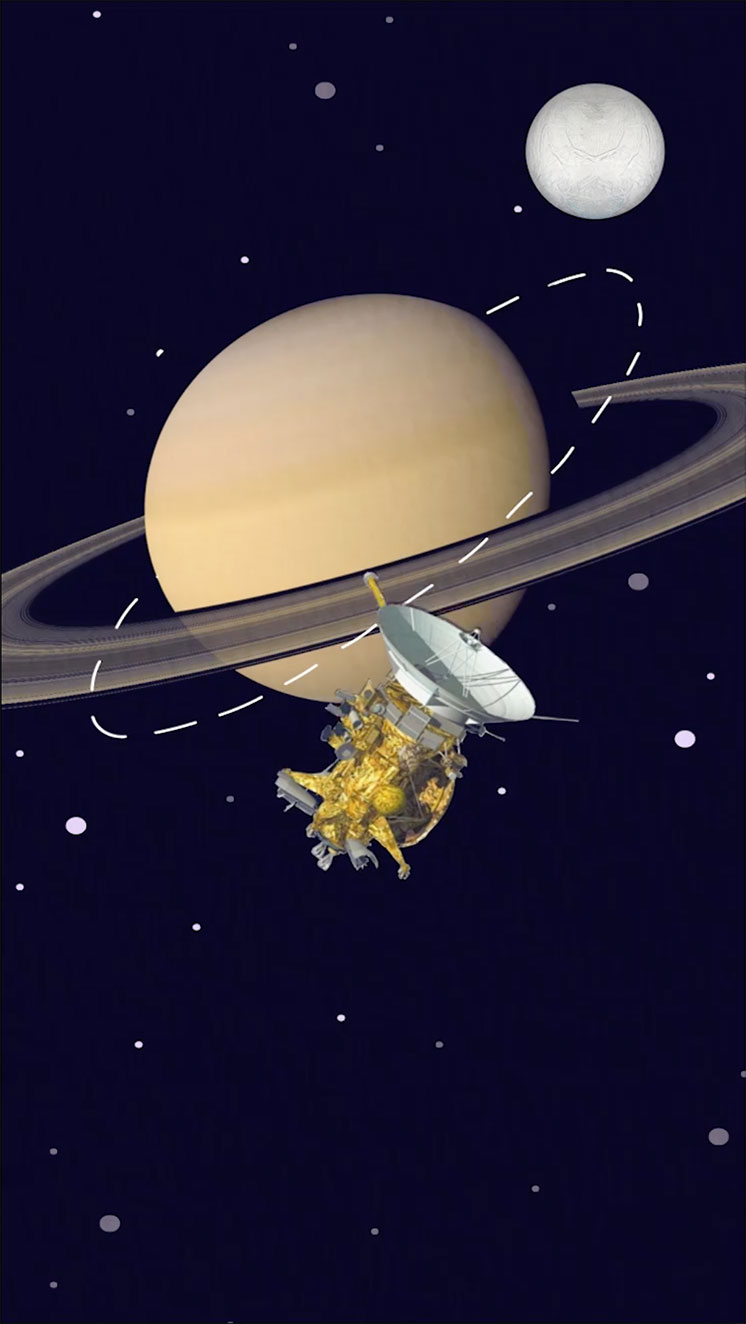

Artwork: Cassini plunged between the rings and the planet's cloudtops

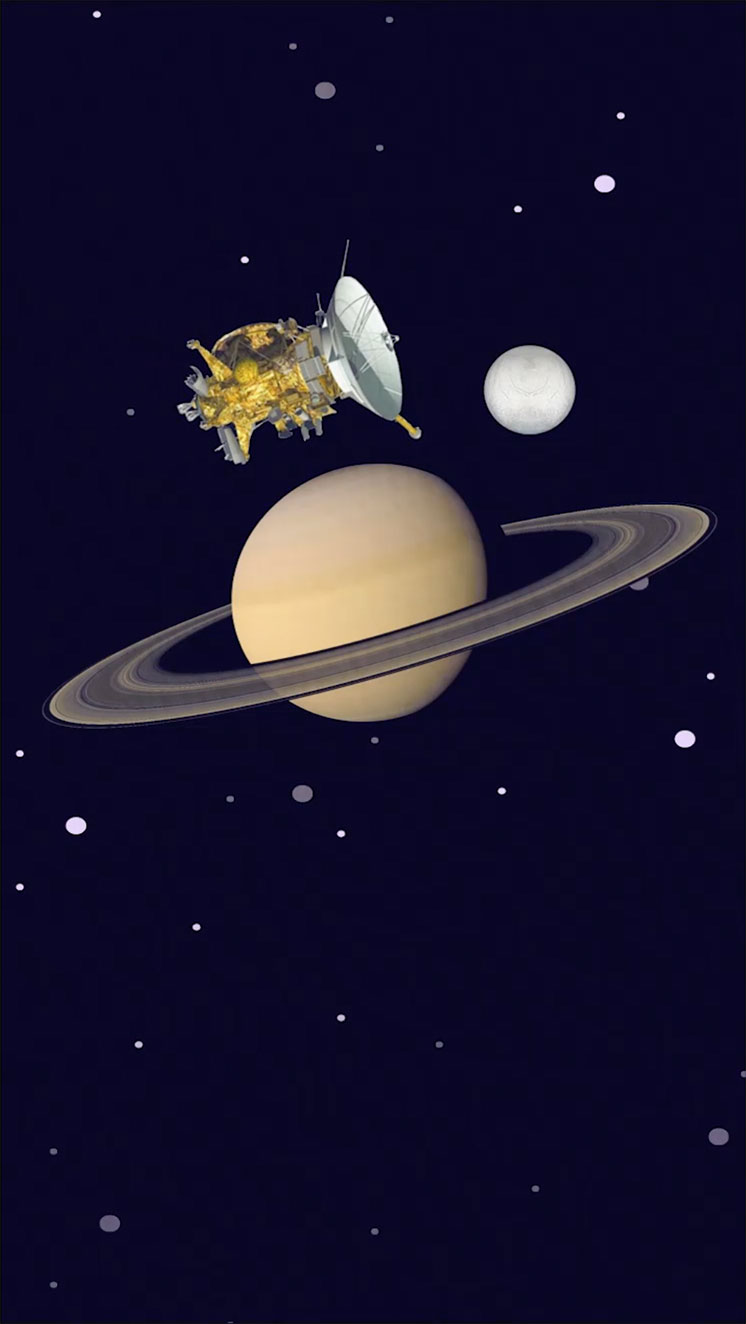

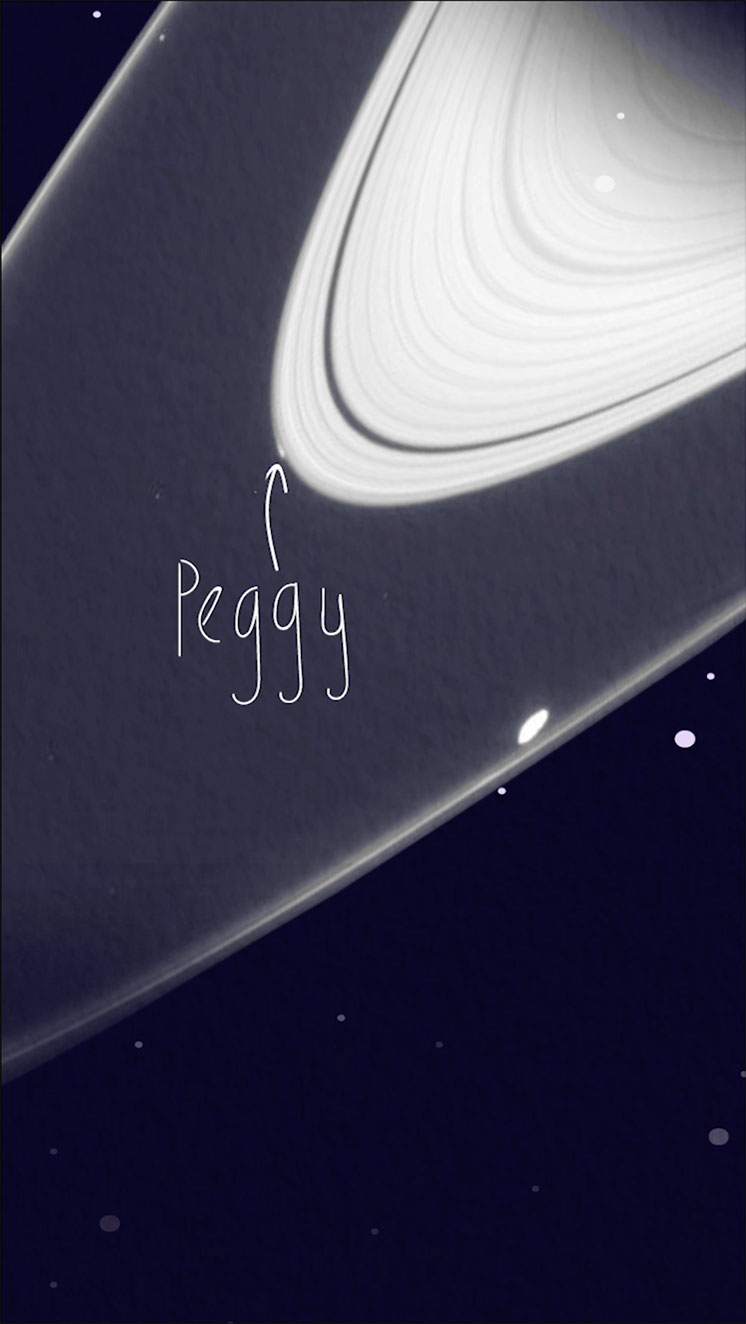

The US-European Cassini mission promised to resolve the argument in its last months at the gas giant.

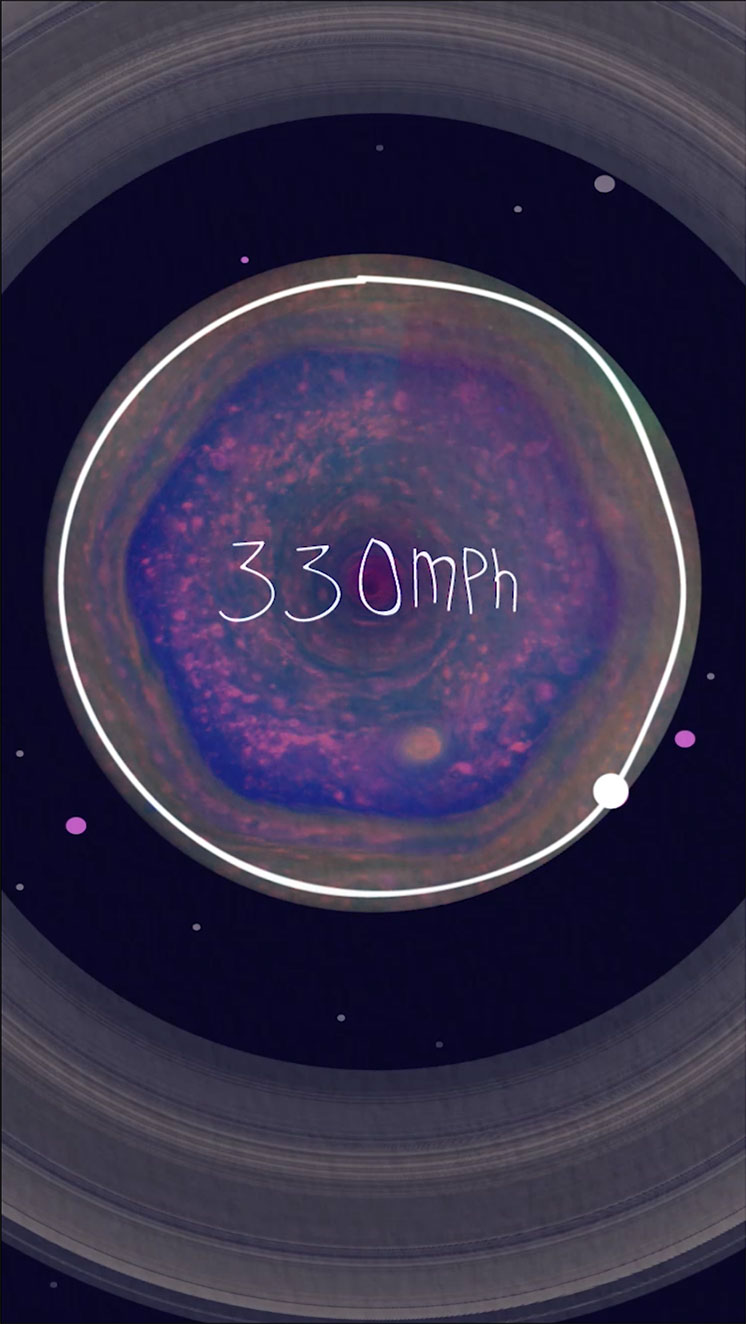

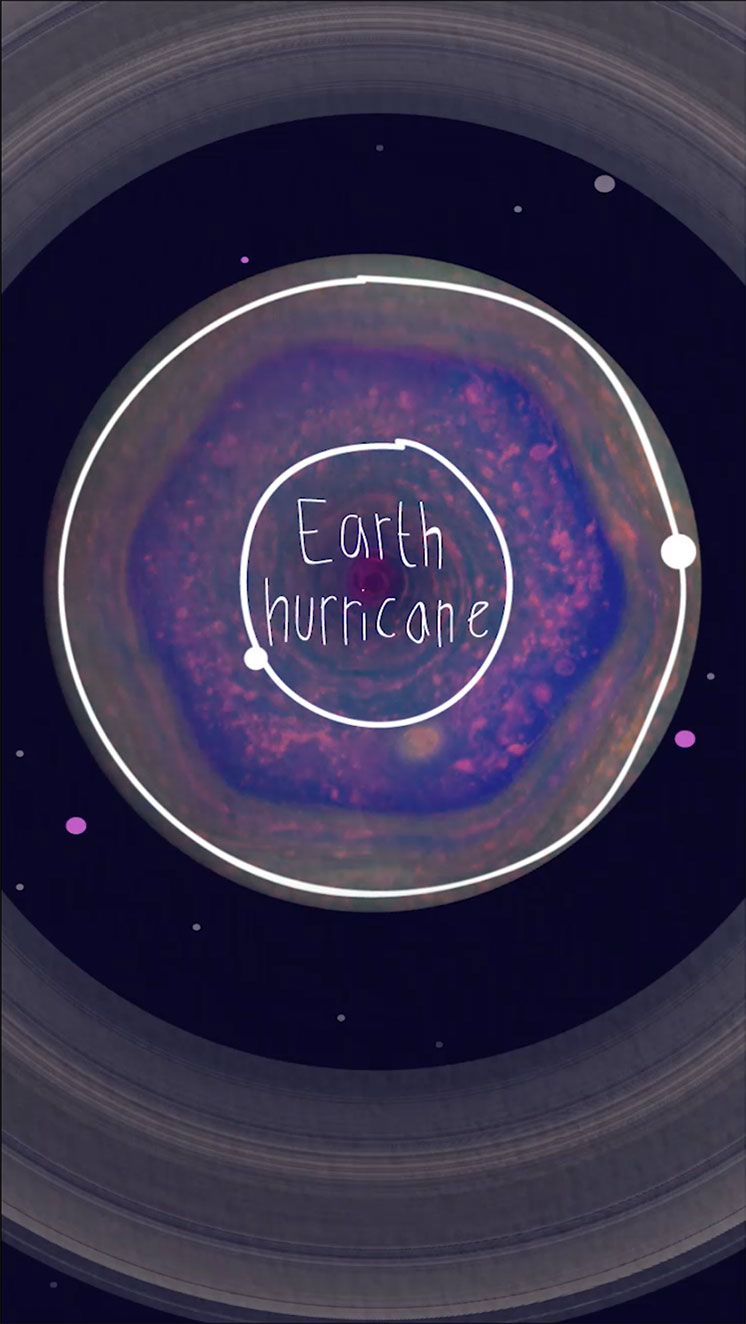

The satellite's end days saw it fly repeatedly through the gap between the rings and the planet's cloudtops.

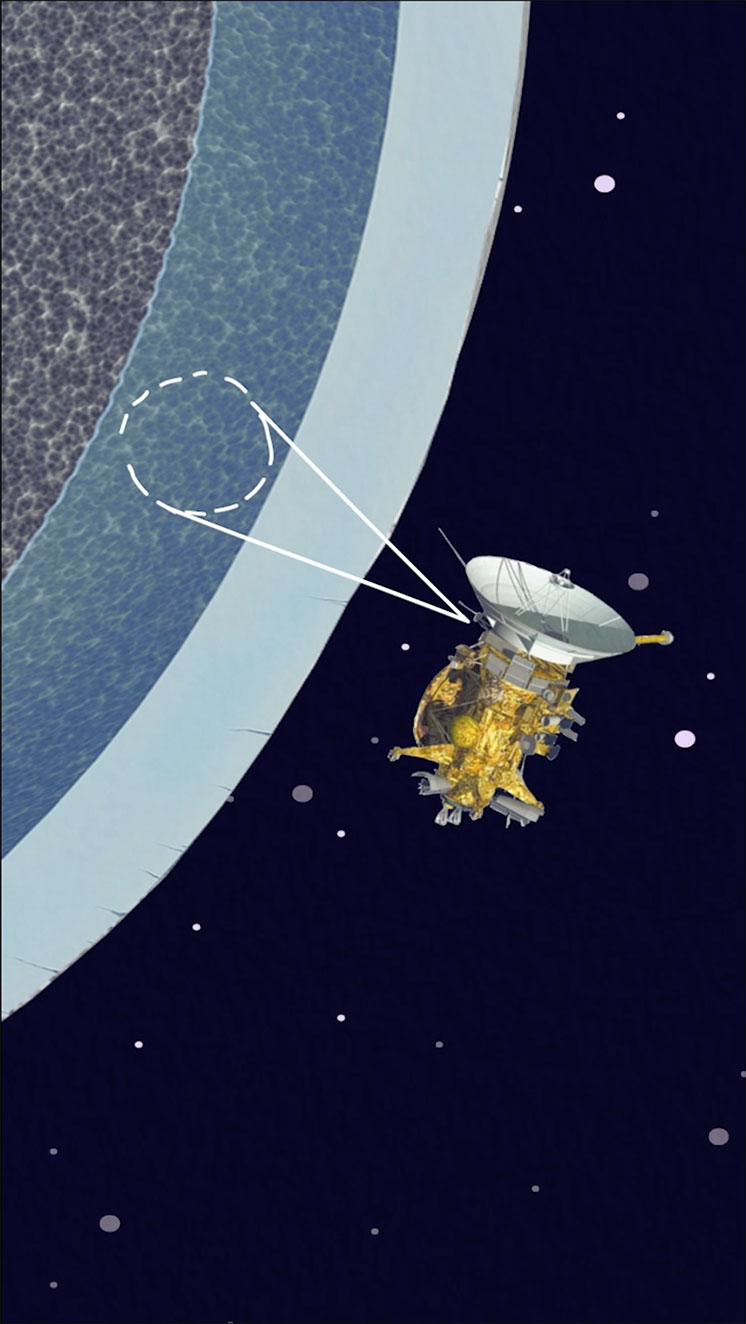

These manoeuvres made possible unprecedented gravity measurements.

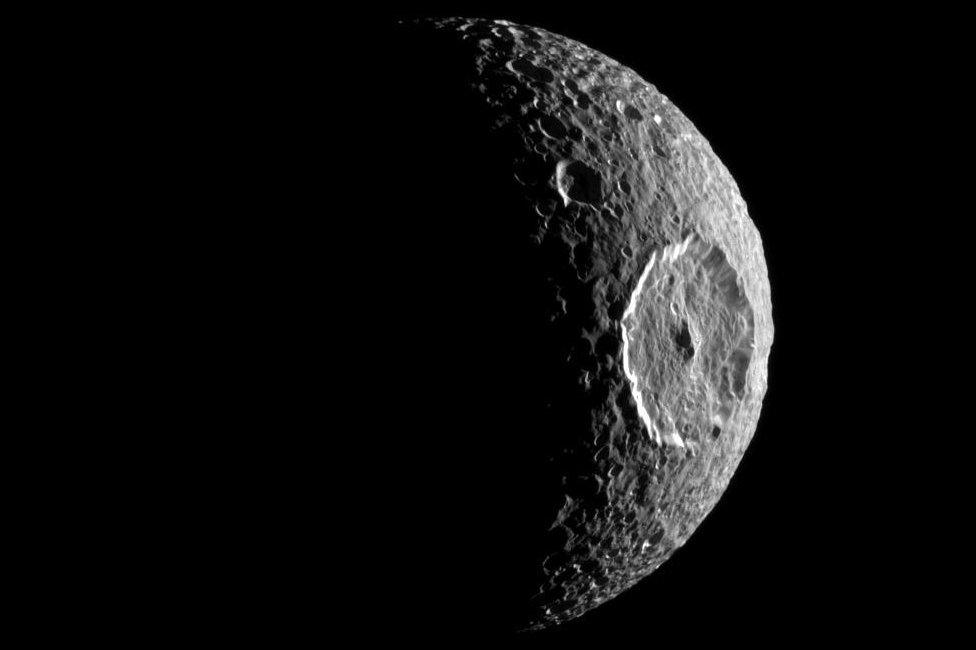

Cassini essentially weighed the rings, and found their mass to be 20 times smaller than previous estimates: something on the order of 15,400,000,000,000,000 tonnes, or about two-fifths the mass of Mimas - the Saturn moon that looks like the "Death Star" weapon in the Star Wars movies.

Mimas: The "Star Wars" moon is a favourite among Saturn fans

Knowing the mass was a key piece in the puzzle for researchers.

From Cassini's other instruments, they already knew the proportion of dust in the rings and the rate at which this dust was being added. Having a definitive mass for the rings then made it possible to work out an age.

Prof Iess's team says this could be as young as 10 million years but is no older than 100 million years. In terms of the full age of the Solar System, this is "yesterday".

The calculation agrees with one made by a different group which last month examined how fast the ring particles were falling on to Saturn, external - a rate that was described as being equivalent to an Olympic-sized swimming pool every half-hour.

This flow, when all factors were considered, would probably see the rings disappear altogether in "at most 100 million years", said Dr Tom Stallard from Leicester University, UK.

"The rings we see today are actually not that impressive compared with how they would have looked 50-100 million years ago," he told BBC News.

"Back then they would have been even bigger and even brighter. So, whatever produced them must have made for an incredible display if you'd been an astronomer 100 million years ago."

Cassini's investigations cannot shed much light on the nature of the event that gave rise to the rings, but it would have been cataclysmic in scale.

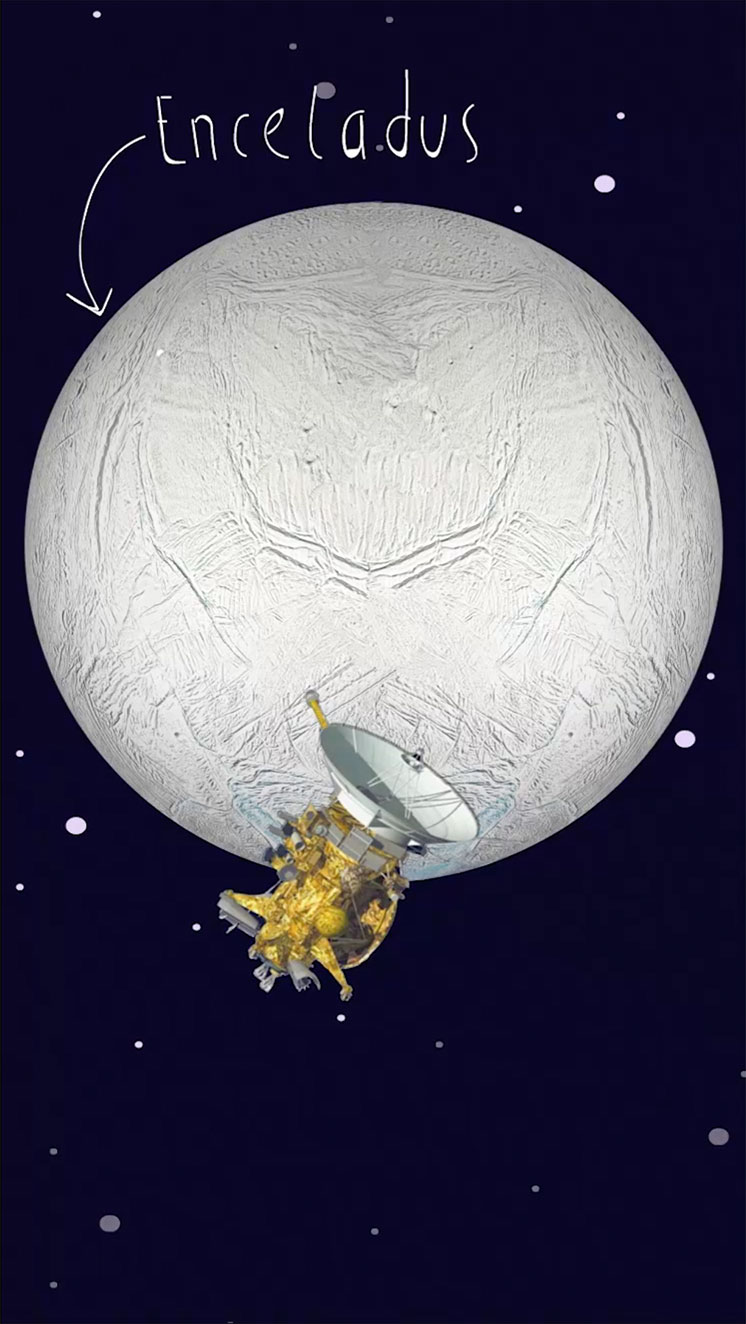

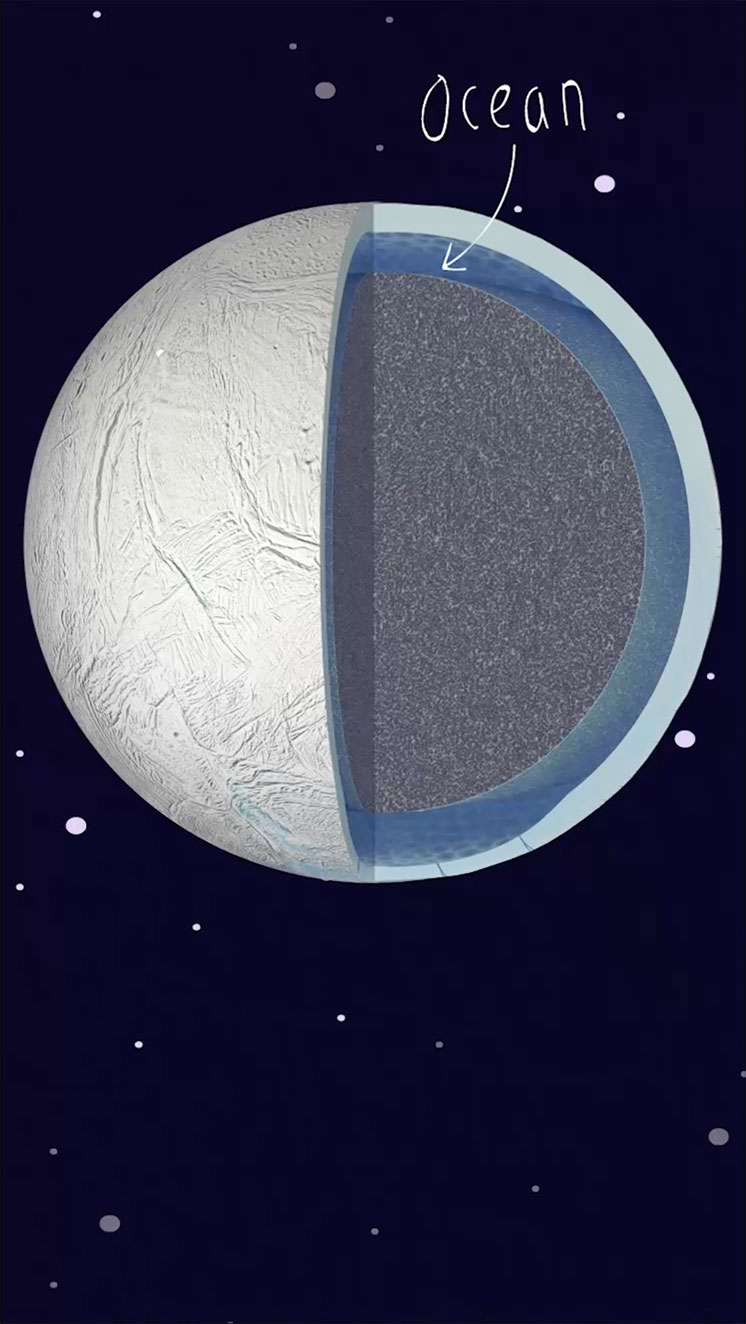

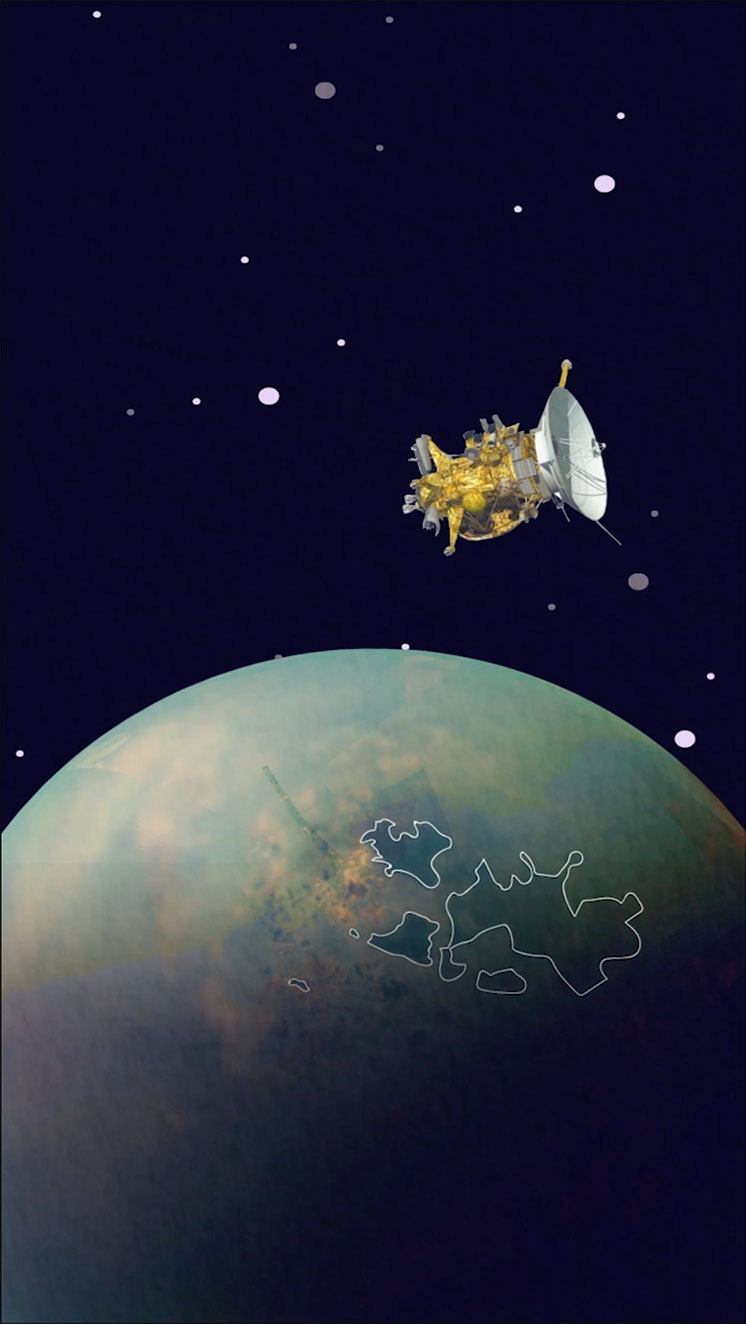

It was conceivable, said Dr Stallard, that the geology of the moons around Saturn could hold important clues. Just as rock and ice cores drilled on Earth reveal debris from ancient meteorite and comet impacts, so it's possible the moons of Saturn could record evidence of the ring-forming event in their deeper layers.

Maybe we'll get to drill into the likes of Mimas and Enceladus... one day.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external