UK team drills record West Antarctic hole

- Published

Keith Makinson: "There are implications for the future of Antarctica and sea-level rise"

UK scientists have succeeded in cutting a 2km hole through the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to its base.

It's the deepest anyone has gone in the region using a hot-water drill.

The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) pulled up sediment from the bottom of the hole and deployed a series of instruments.

The researchers hope the project's data can help them work out how quickly the White Continent might lose its ice in a warming world.

Rutford sediments: How does the ice slide across the bed?

Dr Andy Smith leads the team, which is still at the drill site at a location known as the Rutford Ice Stream.

He says there is immense satisfaction at having reached the bed after so many years of trying. An aborted attempt was made in 2004.

"I have waited for this moment for a long time and am delighted that we've finally achieved our goal," he commented.

"There are gaps in our knowledge of what's happening in West Antarctica and by studying the area where the ice sits on soft sediment, we can understand better how this region may change in the future and contribute to global sea-level rise."

What exactly has the team done?

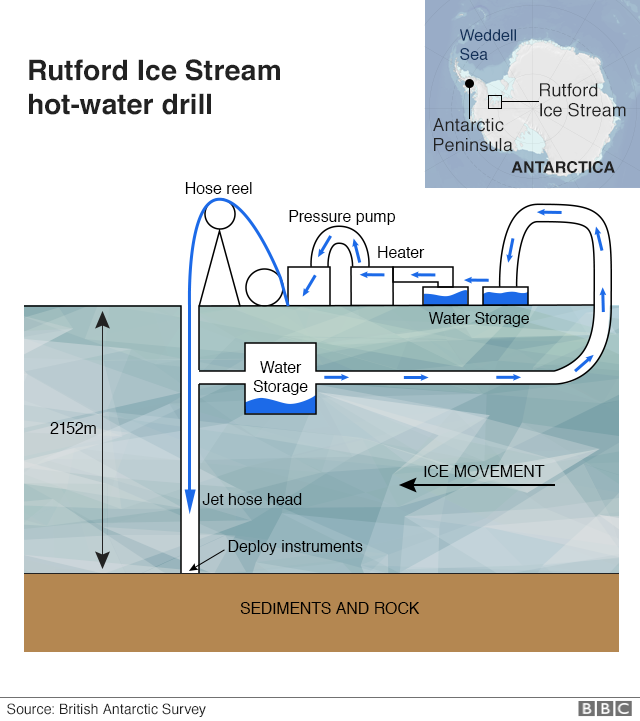

There are a number of ways to cut through the thick Antarctic Ice Sheet.

A popular option is to use a corer, which allows scientists to bring up segments of ice that can then be studied back in the lab.

Another is to blast your way down, using hot water fed through a high-pressure hose.

You can't retrieve ice for analysis this way, obviously. But you can use the opening to do other things.

It is this second technique that the BAS team has employed at Rutford.

The project is called BEAMISH (Bed Access, Monitoring and Ice Sheet History), external.

The approach is very quick - the reported hole was created on 8 January after just 63 hours of continuous operation.

The set-up is tricky to manage, however - not least because as soon as drilling stops, the 30cm-wide incision begins to close in the frigid (minus 30C air temperatures) environment.

What did the BAS team put in the hole?

The drilling system reached 2,152m below the surface of the ice

The scientists are interested in the behaviour of Rutford because it's a pretty typical, fast-flowing, West Antarctic ice stream.

Almost 300km long and 25km wide, it drains a lot of ice into the Weddell Sea.

Researchers want to better understand how it all moves and to do this they need to know the nature of the sediments on which the ice is sliding and how much water might be lubricating its path to the coast.

To retrieve this information, the BAS team grabbed some sediments from the bottom of the hole and positioned instruments that can report back on the speed of the ice stream at its base.

The data will be used to constrain the computer models that seek to predict future Antarctic melting under various warming scenarios.

How deep is this hole compared with others?

BAS has worked to refine the hot-water technique

It is the deepest hole drilled with hot water in the west of the continent.

In the east, the same technique was used some years back to bore marginally more extensive (2.4km) openings at the South Pole for the IceCube experiment, external.

Corers and other drill types have gone down over 3km where the ice sheet is thicker.

BAS is working hard to perfect the hot-water drill. It sees the technology as having wide application.

British scientists used the system in 2012 to try to break through to the under-ice Lake Ellsworth.

It was an audacious attempt to sample a 3.2km-deep environment that has been shut off from the world for thousands of years. But the technology failed on that occasion.

The success at Rutford will surely encourage thoughts of another go at Ellsworth - and if not there, then perhaps at another of the continent's many sub-glacial lakes.

What happens next?

Conditions are hard, with temperatures down to minus 30C

For the moment, the BAS team has plenty of work to do at Rutford.

News has arrived in the past couple of days that a second hole has now been drilled alongside the first.

The desire is to drill a total of four, says team-member Dr Keith Makinson, which will enable the maximum number of instruments to be deployed.

"It's not possible to put them all down a single hole," he told BBC News.

"We're going for two holes at two sites. That's to look at different sediment types.

"There's one site where the sediments are much stiffer and harder, and the other where they're much softer. We want to look at the different properties."

Rutford is a wide, fast-moving ice stream

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external