Rosalind Franklin: Mars rover named after DNA pioneer

- Published

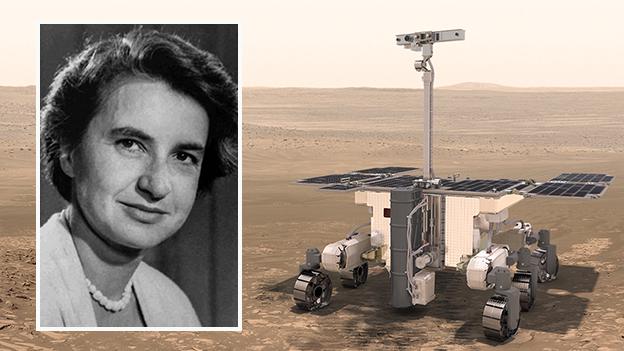

The Rosalind Franklin rover is due to launch to Mars next year

The UK-assembled rover that will be sent to Mars in 2020 will bear the name of DNA pioneer Rosalind Franklin.

The honour follows a public call for suggestions that drew nearly 36,000 responses from right across Europe.

Astronaut Tim Peake unveiled the name at the Airbus factory in Stevenage where the robot is being put together.

The six-wheeled vehicle will be equipped with instruments and a drill to search for evidence of past or present life on the Red Planet.

The unveiling of the name was orchestrated by UK astronaut Tim Peake

Giving the rover a name associated with a molecule fundamental to biology seems therefore to be wholly appropriate.

Rosalind Franklin played an integral role in the discovery of the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid.

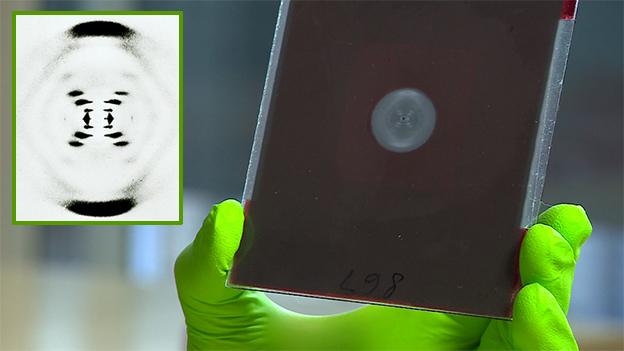

It was her X-ray images that allowed James Watson and Francis Crick to decipher its double-helix shape.

Franklin's early death from ovarian cancer in 1958, aged just 37, meant she never received the recognition given to her male peers.

The attachment to the European Space Agency (Esa) rover will now see her name travel beyond Earth.

"In the last year of Rosalind's life, I remember visiting her in hospital on the day when she was excited by the news of the [Soviet Sputnik satellite] - the very beginning of space exploration," Franklin's sister, Jenifer Glynn, said on Thursday.

"She could never have imagined that over 60 years later there would be a rover sent to Mars bearing her name, but somehow that makes this project even more special."

Final assembly of the rover is under way at the Airbus factory in Stevenage

Who was Rosalind Franklin?

In 1952, Rosalind Franklin was at King's College London investigating the atomic arrangement of DNA, using her skills as an X-ray crystallographer to create images for analysis.

One of her team's pictures, known as Photo 51, provided the essential insights for Crick and Watson to build the first three-dimensional model of the two-stranded macromolecule.

It was one of the supreme achievements of 20th Century science, enabling researchers to finally understand how DNA stored, copied and transmitted the genetic "code of life".

Crick, Watson, and King's colleague Maurice Wilkins, received the 1962 Nobel Prize for the breakthrough.

Franklin's untimely death meant she could not be considered for the award (Nobels are not awarded posthumously). However, many argue that her contribution has never really been given the attention it deserves, and has even been underplayed.

Photo 51 was a eureka moment for Crick and Watson

How was the rover name selected?

Up until now, the rover has simply been known by its Esa project name - ExoMars.

In the UK, many people have also become familiar with the names given to the prototype robots that Airbus built to trial the vehicle's technology.

These have been names like Bridget, Bruno and Bryan. The "B" letter is a play on the word "breadboard" - the term describing the bald plate engineers use to design new electronic circuitry.

But it has become common practice now for space missions to have a ceremonial name.

Sometimes these are just glorified acronyms that summarise the mission goals, but often they reference a historical figure who made a significant contribution in a relevant field of science.

For recent European Space Agency projects, Italian scientists have been honoured, including Giuseppe "Bepi" Colombo (Mercury mission) and Giovanni Schiaparelli (a previous Mars lander).

Rosalind Franklin was chosen by a UK-led panel who sifted through 35,844 suggestions.

"We had the usual clutch of acronyms, deities and inspirational words, but when we got down to the short shortlist - it was the obvious choice. It ticks all the boxes," Dr Sue Horne, the head space exploration at the UK Space Agency, told BBC News.

Britain essentially got the naming rights because it has put most money into the rover.

"Rover McRoverFace" was suggested but the UK Space Agency made it clear at the outset that there would be no repeat of the furore that accompanied the naming of Britain's new polar ship.

Take a closer look at the Rosalind Franklin design

At what stage is the rover project?

The rocket that will send the Franklin rover to Mars is booked to launch in July/August 2020. The various components needed for the mission are gradually coming together under the direction of Esa and its partner on the venture - the Russian space agency, Roscosmos.

British engineers are on target to deliver a finished robot at the end of July. This will go first to an Airbus test centre in Toulouse, France. From there, it will head east, to Cannes.

On the Côte d'Azur, the Franklin rover will be integrated with its German "cruise" capsule, which will carry it to the vicinity of the Red Planet, and the Russian landing mechanism, which will have the all-important job of putting the rover down safely on the surface of Mars in March 2021.

From Cannes, these elements go to the Baikonur Cosmodrome to be mated with the launch rocket.

The schedule is tight, conceded Prof Jan Wörner, the director-general of Esa: "It's a challenge but we're working really hard to make the launch date."

Airbus has built a special "cleanroom" to assemble the rover. The Franklin vehicle's parts are being brought to Stevenage from across Esa member states and Canada. The North Americans are making the locomotion system - the wheels.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external