'Time bomb' warning on mining dam disasters

- Published

Brazil's mining dams: A disaster waiting to happen?

The catastrophic collapse of a dam at a mine in Brazil has exposed a darker side of an industry that the world depends on.

At nearly 800 sites across the country and thousands more around the world, dams contain huge loads of mining waste.

One British scientist, Dr Stephen Edwards of UCL, has warned that "we are sitting on a time bomb".

He told BBC News that further disasters were inevitable.

Over the last few days in the heart of Brazil's mining belt, I've been investigating two very different sites where the risks of massive damage seem plausible.

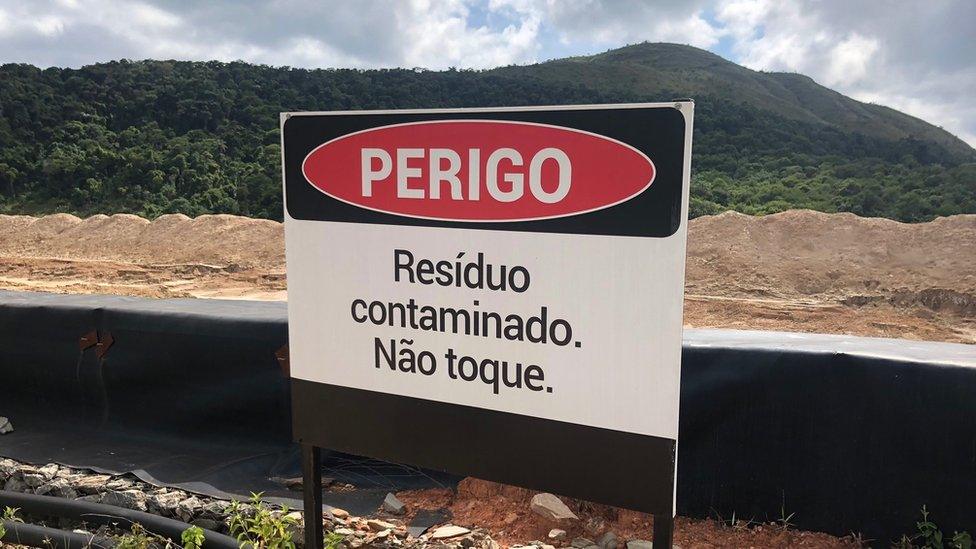

A sign warns against contamination at the site

One is a vast lake of sludge perched high above a nervous community; the other is an abandoned gold mine at risk of leaking poisons.

Why are there dumps of mining waste?

The answer begins with the world's growing demand for metals such as steel which is used to make everything from buildings to ships to cars.

The key ingredient of steel is iron ore which is extracted from the ground in huge mines - Brazil is one of the world's largest producers.

Brazil is one of the largest extractors of iron ore, among other mining activities

The ore is broken up, and because only a small fraction of the rock is actually iron, the vast majority is unwanted, a by-product that's thrown away.

And the cheapest way to dispose of these remains is to create what's called a "tailings pond" - a rather genteel term for a dumping-ground sealed with a dam.

Are these dumps easy to find?

Not always. The mining companies tend to tuck them away in valleys in the hills.

We used satellite mapping to find one of the largest tailings ponds in Brazil, a site called Maravilhas II, owned by the mining giant Vale which also owns the dam that failed last month.

Stretching as far as the eye can see is what looks like a sea of red mud, streaked with swirls of black and grey, a mass of sludge.

Hundreds are dead or missing following the Brumadinho dam collapse left

It was just this kind of material, as heavy as wet cement, that escaped in a torrent at Brumadinho killing, 169 people and leaving nearly 200 more still missing.

The waste is held back by a dam that's constructed in a way unique to the mining industry.

Instead of using steel and concrete, as is typical in dams at reservoirs holding water, mining barriers are made of mining waste itself, band upon band of compacted sludge.

In the case of Maravilhas II, the dam stands an astonishing 90m high, a towering grass-covered wall raised in layers over the past 20 years.

What are the dangers?

According to Dr Stephen Edwards of University College London's Hazard Centre, there are possibly thousands of dams of this kind around the world.

"We are sitting on a time bomb. The big problem is that we don't know which offer the greatest threat and where they are situated."

Dr Edwards says that although the number of failures is decreasing, the size of the sites is increasing so the impacts of collapse are becoming greater.

"Many tailings facilities are the biggest structures on the planet and that trend will increase and, if we are getting bigger facilities, and some of those might fail, then we are going to end up with bigger disasters."

So what's it like living in the shadow of a dam?

For Cristiani Magalhaes, whose home is a few hundred metres of the massive Maravilhas II dam, it's a nightmare.

"I don't sleep anymore since what happened in Brumadinho," she tells me. "It was a warning: is the same going to happen here?"

Her community group has created a computer simulation showing the homes that would be engulfed if the dam collapsed.

And the fact that the structure is officially rated as having a low risk of failure is no consolation - that was the rating given to the dam at Brumadinho.

Cristiani says that Vale has provided no information about the dangers or whether there's an evacuation plan.

"I'm pregnant and my little boy keeps asking me when it's going to happen," she says, "how we're going to run away, will we have time to take my toys?"

I put these allegations to Vale but had no response.

Compared to other countries, Brazil allows dams to built close to homes and, because the properties can be cheap, many people in these locations are poor.

One specialist in the Brazilian mining industry, Prof Klemens Laschefski of the Federal University of Minais Gerais, is scathing about this practice.

"It is a scandal," he told me, "it is a form of environmental racism."

What other threats does mining waste pose?

A bumpy drive from the hill town of Rio Acima leads to an abandoned gold mine that represents another kind of horror story.

While the threat from iron ore mines is the sheer volume and weight of their waste, the danger from gold mines is their toxicity.

The ore that contains gold can also contain arsenic, and a common technique for separating out the gold involves cyanide.

Since the last owners of the mine pulled out, the machinery has rusted, pools of poisonous liquid have formed and enormous dumps of toxic waste are left behind dams that no one is maintaining.

The fear is that if the barriers break - and they do not look sturdy - the waste could contaminate an important watershed supplying some 3.5m people downstream.

A local environmental group, Gandarela, guided us around the site - staying a safe distance from anything hazardous and keeping our visit as brief as possible.

One of the group's leaders, Saulo Albuquerque, said the danger could even reach the sprawling urban area of the state capital, Belo Horizonte.

"If a very heavy rain falls, who's going to guarantee this dam won't collapse?" he said.

Surely there are government controls?

Back in 2015 another dam in the region collapsed, killing 19 people and poisoning an entire river system, and many local people and observers assumed that much tougher controls on the mining industry would follow.

Instead, experts were stunned to see the state administration become more lenient with a policy called "flexibilisation" - licences for mines and dams could be approved more easily.

Prof Laschefski says the mining industry, as a major employer and revenue provider, has profound influence - and he points to analysis showing that three-quarters of the politicians in the state assembly received donations from mining companies.

There are initiatives to try to secure the most vulnerable sites but the sheer number is daunting and the costs will be astronomic.

The world needs metals like iron but the staggering loss of life at Brumadinho shows that their extraction can come with a very heavy price.

Follow David on Twitter., external