Fast fashion: 'Penny on a garment' to drive clothes recycling

- Published

- comments

MPs want to see more sustainable designs and repair services

Clothing brands and retailers should pay a penny on every garment they sell to fund a £35m annual recycling scheme.

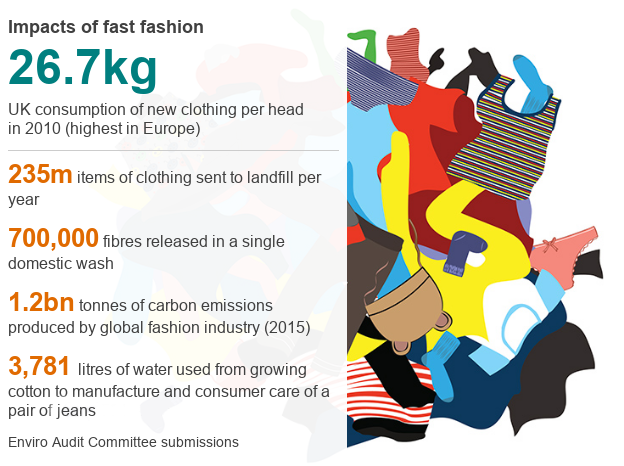

That's the view of MPs, who say "fast fashion" is a major contributor to greenhouse gases, water pollution, air pollution and over-use of water.

And they urge the government to force clothing manufacturers to pay more towards collecting and recycling the waste they create.

Green campaigners argue the MPs' recommendations are really quite tame.

They're calling for an end to what they regard as the over-consumption of clothes.

Why is it fashionable to fret about fashion?

The fashion industry creates jobs worldwide and is said to be worth £28bn to the UK economy - but it is estimated to produce as many greenhouse gases as all the planes flying in the world.

Libby Peake, from the think-tank Green Alliance, told BBC News: "One of the areas in which you could make a big difference in terms of your personal climate change impact is by reducing the amount of clothes you buy and keeping them for longer, then donating them to charity shops to keep them in the national wardrobe."

The clothing trade consumes vast volumes of fresh water and creates chemical and plastic pollution. Manmade fibres are found in the bellies of creatures in the deep ocean.

The Environmental Audit Committee is also concerned about the use of child labour, prison labour, forced labour and bonded labour in the manufacture of clothes.

What is the industry doing to improve?

Some progressive firms now offer vouchers to shoppers taking back used garments. Marks & Spencer is among the leaders with its "Plan A" (because there's no Plan B).

The Global Recycling Council commends other firms, including Adidas, which will use only recycled polyester in all shoes and clothing by 2024; and Bottletop, which collaborated with Mulberry to launch a luxury bag made entirely from up-cycled materials (pre-used goods given extra value).

But the MPs say they've received inadequate commitments from JD Sports, Sports Direct, Amazon UK and Boohoo.

Spokespeople for some of these firms say they've taken other positive measures that haven't been properly registered by the MPs.

The MPs' report says it is an open secret that some fast-fashion factories in places such as Leicester are not paying the minimum wage - and the same firms are selling clothes so cheaply that they are being treated as single-use items.

The MPs say in the UK we buy more clothes per person than any other country in Europe - and a glut of second-hand clothing is swamping the market and depressing prices for used textiles.

Less than 1% of material used to produce clothing is recycled into new garments at the end of its life.

Fashion bloggers give their tips on loving what you have and recycling

What can be done?

The committee chair, Mary Creagh, said: "Fashion retailers should be forced to pay for the impact of their clothes when they're thrown away."

She said the government should end throwaway fashion by incentivising companies that offer sustainable designs and repair services.

"Children should be taught the joy of making and mending clothes in school," she told us.

"We've got to help teenagers get an emotional attachment to their clothes instead of just wearing them a couple of times, getting photographed for Instagram and then chucking them away.

"All consumers have got to accept they need to buy fewer clothes - then mend them if they're torn, or rent or share them."

The MPs conclude that a voluntary approach to improving the sustainability of the fashion industry is failing - with just 11 fashion retailers signed up to an agreement to reduce their water, waste and carbon footprints.

The committee says big retailers should be obliged by ministers to comply with high standards on the manufacture and recycling of clothing.

What does industry say?

Peter Andrews, from the British Retail Consortium (BRC), told us a growing number of stores were providing take-back schemes for unwanted clothes, and introducing stock made from recycled materials.

He didn't immediately reject the idea of a penny levy on clothes, and said retailers were willing to discuss how much of a role they should take in dealing with garments where they're thrown away.

He said: "The sustainability of fashion is a high priority for BRC members - the transparency they have shown and the level of engagement with the inquiry reflects that."

Sophie Gorton, an associate lecturer in textiles at Chelsea College, is a long-standing proponent of sustainable fashion.

She told us there were signs of hope that the industry was starting to change.

"For years we have asked the people who make textiles and yarn about the sustainability of their products and they just haven't wanted to know," she said.

"Now, suddenly, they're interested in what makes sustainable hemp or linen - they really want to think about it. It's a very exciting time."

Claire and Emily are trying to empower people to make their own clothes

Will the MPs' solve the fast fashion problem?

Clare Farrell, a member of the climate group Extinction Rebellion and also a fashion lecturer, says the committee is aiming at the wrong target.

She admits it's better to recycle clothing fibres than throw garments away, but she says the real problem is consumer capitalism: people are putting an intolerable strain on resources simply because they're buying too many clothes in the first place.

"We need a change in mindset," she told us. "Kids buy clothes, wear them a few times and then get rid of them. How do we tackle that? It's the nature of consumer capitalism and it's a very, very big problem for us all.

"Fashion is a big part of the economy, but we can't tackle the problems unless we admit that economy is killing us the way it's currently run."

Follow Roger on Twitter @rharrabin, external