Fund to boost female and black physicist numbers

- Published

Prof Jocelyn Bell Burnell donated her prize money to help others follow in her footsteps

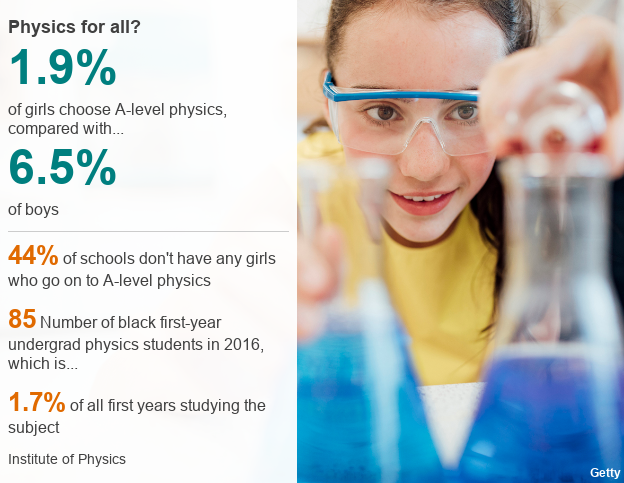

The Institute of Physics is launching a bursary scheme to help female and black students to become physics researchers.

The scheme is funded by one of the world's leading astronomers, Prof Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell.

The discoverer of pulsars donated the £2.3m she won as part of an international science award.

The initial aim is to increase the number of female physics researchers in the UK from the current level of 22% to more than 30% in the next 10 years.

The Bell Burnell Graduate Scholarship Fund, external will also support students from low socio-economic backgrounds and those who qualify for refugee status.

Ozi Kamalu: Following a passion

Ozi Kamalu was obsessed with space as a child

Ozi Kamalu is studying astrophysics. She was also obsessed with space as a child. She was one of five girls in her AS physics class, but all the others dropped out because, she says, it was a "very laddish environment". There were very few BME students studying science at her school and very few black people at her university.

Prof Bell Burnell was awarded a Breakthrough Prize last September for her discovery in 1967 of radio pulsars - rapidly rotating star remnants.

The pulsar discovery was recognised with a Nobel Prize in 1974, although it was her male collaborators who received the honour.

In an effort to remedy some of the injustices women as well as black and refugee students face in entering a career in physics, Prof Bell Burnell donated her entire prize money to the Institute of Physics (IoP).

In an interview with Physics World, external, Prof Bell Burnell said she hoped that the scheme would bring more diversity into physics departments.

"I have been concerned about the shortage of women in physics for a very long time. I'm one of the founders of the Athena SWAN scheme, external (to support diversity in universities).

"I never thought I'd have this kind of money, so it would be nice to enable those who want to - refugees and people from minority and other under-represented groups - to stay on and do PhDs."

Applications are invited from students who are unable to meet the costs of their chosen three-year post graduate course, which is the first step in a research career.

They will be considered by a panel representative of the communities the bursaries are intended to support.

The principal consideration will be the applicant's financial need, and the money will go towards fees, transport and living costs.

Najnin Sharmin: 'Financial support'

Najnin Sharmin is researching optical imaging

Najnin Sharmin, from Bangladesh, is specialising in optical imaging at University College Dublin (UCD). She says the most difficult period for her was between finishing her masters degree and getting accepted on to her PhD studentship. She struggled financially for eight months, a time that she describes as "nerve-wracking".

Successful candidates will also be able to access the IoP's fund to pay for carers for children or dependent relatives.

Prof Bell Burnell hopes the IoP bursary scheme will send a signal to those that are bright enough to become researchers but lack the confidence.

"In my case, I probably didn't need the money, but I needed assurance that people like me could do PhDs," she said.

"When I was an undergraduate studying physics at the University of Glasgow in the 1960s, it was the 'tradition' that when a woman entered the lecture theatre, everybody whistled and stamped and catcalled.

"It wasn't nice and I wasn't sure I was going to make the grade.

"This kind of fund says it's not just middle-class white males who do PhDs in physics."

Stephanie Merritt: A second chance

Stephanie Merritt left school with just a few GSCEs

Stephanie Merritt is researching the atmospheres of planets orbiting distant stars at Queen's University Belfast. She fell in love with space as a child, but never thought that, as a woman from a working class background, it was ever something with which she could become involved.

Stephanie left school at 15, achieving only a handful of GCSEs. She worked lots of minimum wage jobs over many years before saving up enough money to study at her local technical college when she was 22. Stephanie was 25 when she began studying physics at university. She said she felt like an impostor and felt alienated because of her class and sex. Nonetheless, she got a first class degree.

Prof Paul Hardaker, who is the chief executive of the IoP, is keen to get that A-level figure up to 30% because social science studies show this proportion seems to provide a tipping point and lead quickly to a 50:50 gender balance.

"We are absolutely determined to break through the 30% at A-levels barrier. This fund on its own won't solve the problem, but we want to use it as part of an effort to create momentum for that change."

Prof Hardaker wants to use the scheme to understand why women and black researchers are under-represented in a field that is regarded as progressive and internationalist in its outlook - more so than other professions such as banking and the law.

"If we can get a handle on what interventions can make the most difference, we can make a real difference," he said.

"Everyone should have an opportunity to study physics because it opens up so many opportunities.

"It brings economic opportunities and opens up career prospects. But it is being denied to some individuals because it is not accessible."

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

- Published6 September 2018