Planet Venus: Hopes rise of new mission to the hothouse world

- Published

The longstanding idea that Venus is geologically dead is a "myth", scientists say.

And new research may be on the verge of ending that perception forever.

Hints of ongoing volcanic and tectonic activity (activity in the planet's outer shell) suggest that, while different to the Earth, the planet is very much alive.

Now scientists are building new narratives to explain the planet's landscape.

This includes an idea that proposes the existence of "toffee planets". This theory incorporates knowledge accumulated through studying exoplanets.

The new ideas have been discussed here at the 50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) in The Woodlands, Texas., external

Historic missions

The focus on Mars over the last few decades has transformed our view of that planet's geology.

In the meantime, the researchers who study Venus's surface have relied heavily on data from Magellan - a Nasa mission that ended in 1994. A European mission, Venus Express, and a Japanese spacecraft, Akatsuki, have been there since, but both are focused on atmospheric science.

After years of feeling like a new mission would never happen, there is a sense that the tide might finally be turning.

The European Space Agency (Esa) is evaluating a Venus mission, called EnVision, alongside two astronomy proposals - Theseus and Spica. Other concepts are also being proposed to Nasa.

Early career researchers are now choosing to join the field again in numbers. And scientists with backgrounds in other disciplines are lending their expertise, bringing new ideas.

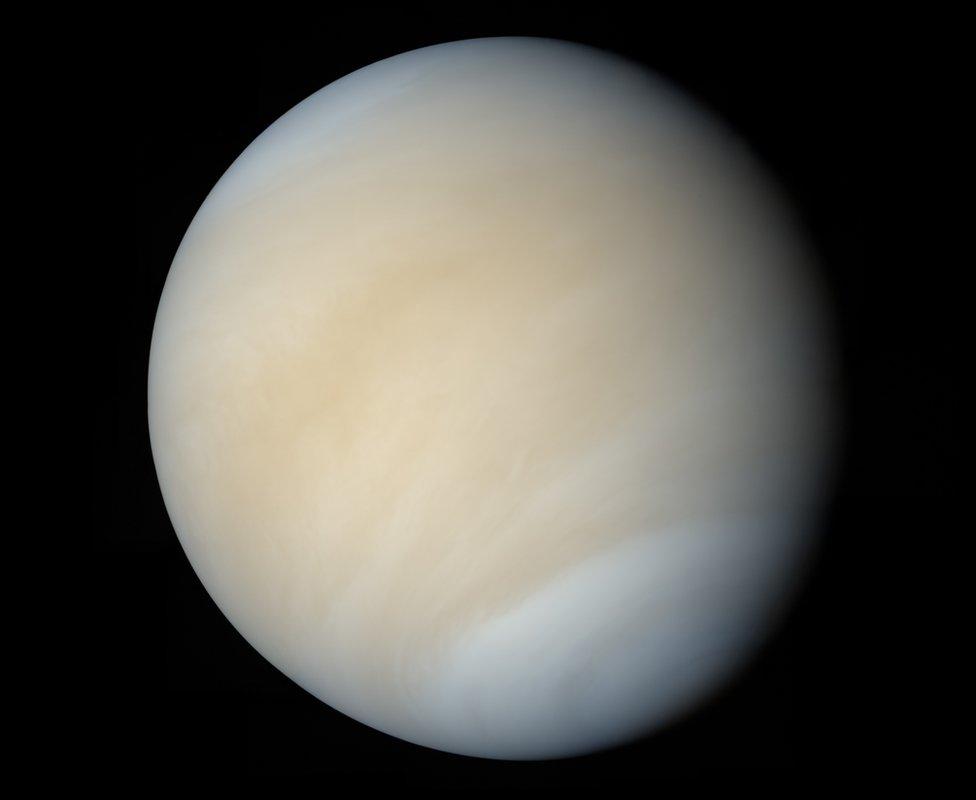

Venus is covered in a thick carbon dioxide atmosphere

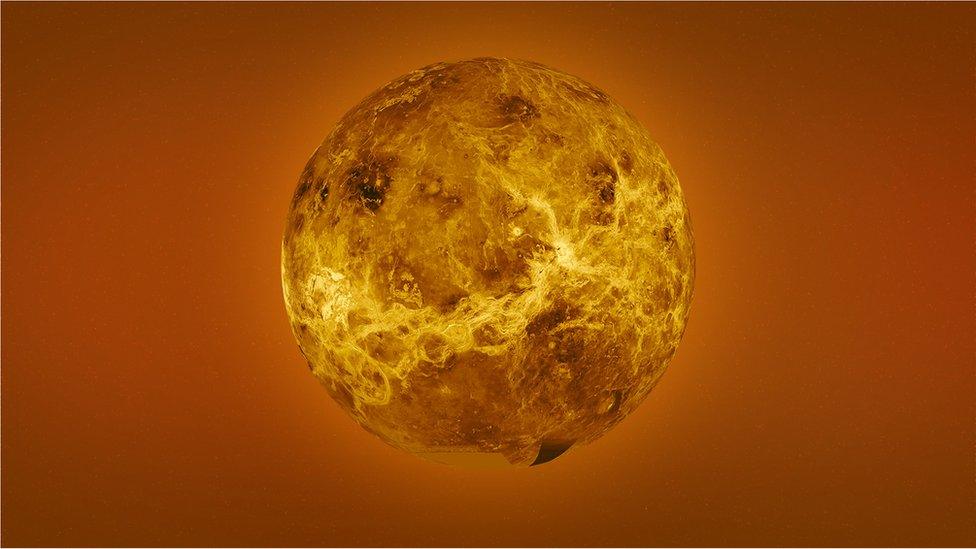

Venus is a hothouse world, with a surface temperature of 500C - hot enough to melt lead. But it's not just the heat that makes it inhospitable: the planet's thick atmosphere has cranked the surface pressure up to 90 bars. That's the equivalent to what you'd experience 900m below the sea.

But Venus and Earth started out being much more similar. "They probably started out as twins, but they've diverged," said Dr Richard Ghail, from Royal Holloway, University of London, who is the principal investigator on EnVision.

"The Earth in that time has gained oxygen and life and has - essentially - quite a cold climate, whereas Venus has got incessantly hotter and drier over a long period."

Lost water

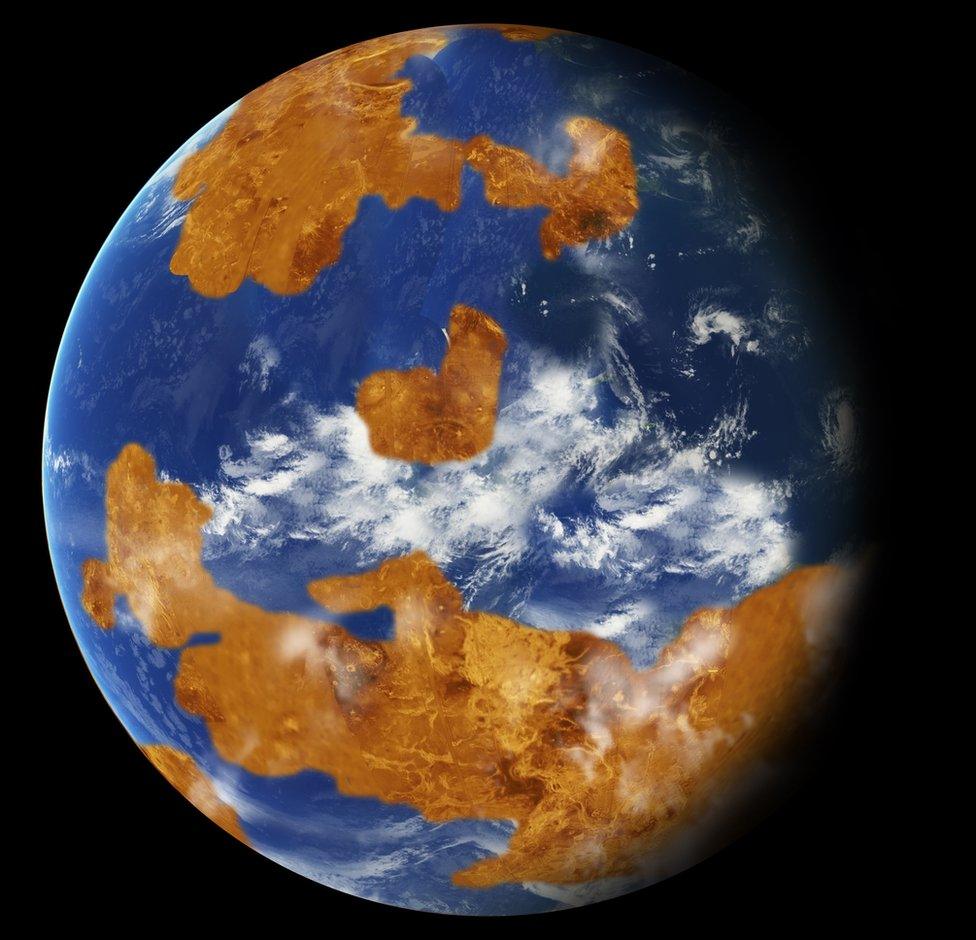

Like Mars, then, Venus might even have had the right conditions in the past for life. But Dr Ghail says that while the Red Planet could have hosted large bodies of water on its surface for about 100 million years, Venus could have harboured oceans for more than a billion years of its early history.

How and when it lost that water is just one of the puzzles scientists want new missions to shed light on. It's fate might even present an extreme future pathway for the Earth.

The history of Venus exploration with robotic probes goes back more than 50 years. If the US has become synonymous with Mars exploration, it was the Soviets who stamped their mark on our nearest neighbour in the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

Artwork: Early Venus might have harboured oceans on its surface for more than a billion years

They launched nearly 30 probes towards the planet, with several notable failures. But the successful missions sent back crucial data, including images of the surface. One probe made a detection of what could have been lightning, while others analysed rock samples, which were found to be basalts - similar to general types found on Earth.

Part of the resurgence of interest in Venus centres around the type of geological activity going on, and what it may tell us about rocky planets in general.

Tectonic activity

Venus is thought to lack plate tectonics, the process responsible for recycling the Earth's crust. But the notion that Venus has essentially been "dead" since an outpouring of volcanism hundreds of millions of years ago is incorrect in the view of a growing number of researchers.

Many signs of tectonic activity on Earth, such as networks of ridges and faults, can be found on Venus.

The Soviet Venera 13 probe sent back images of the surface

Dr Ghail has identified signs that Venus's crust is broken up into blocks measuring on the order of 500-1,000km across, which move around slowly in much the same way that pack ice floats on an ocean, pushing and rubbing against each other. The process is driven by convection (the process of heat transfer which pushes hotter material upwards and cooler, denser material down) in the mantle region below the crust.

"They are moving into the block next to them, and that's moving the block next to it and so on. You can link those things together and see that everything is moving towards Ishtar in the northern hemisphere," the Royal Holloway researcher told BBC News.

Ishtar Terra is one of the main highland regions of Venus, sometimes described as a "continent".

"I think you take enough pack ice, you squeeze it into one place, thicken it up and you make a big high plateau," Dr Ghail explained.

Toffee planet

Dr Paul K Byrne, from North Carolina State University, says this idea might fit in well with a theory he has been developing about the relationship between the thickness of the lithosphere, the rigid outer shell of a planet, and its gravity.

"The basic thinking is this: because on a world with lower gravity, you might get a thicker layer, we reasoned that if you've got higher gravity - like a Super Earth (a class of medium-sized planet seen around other stars but not in the Solar System) - then that brittle layer would be proportionally thinner."

He calculates that particular combinations of planetary mass, atmospheric pressure and composition, as well as the distance of a planet to its star, can produce something called a toffee planet, where the lithosphere is very thin.

"For example, one of the ways that lava might come up is that magma will rise to some depth and make its way through fractures or dykes. But if you don't have a thick layer… then it won't come up in that nice easy way. It might come up in a larger mass, but it won't be concentrated so you won't expect to find chains of volcanoes," Dr Byrne explained.

With regards to Venus, he said: "Some parts of Venus we think might be quite thick, but some parts of Venus, in the lowlands, the brittle layer might be quite thin."

Under that scenario, the idea of blocks of crust moving like pack-ice becomes plausible, said Dr Byrne. If selected, EnVision will carry a synthetic aperture radar to test some of these ideas.

"I think this is happening, other people think nothing's happening. The other possibility is that it's really Earth-like and really active… the only way to distinguish between those is with radar. We do that routinely on Earth, so let's take an Earth-observation radar to Venus," said Dr Ghail.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external