What does air pollution do to our bodies?

- Published

UK scientists estimate air pollution cuts British people's lives by an average of six months

The countdown has begun to the launch of one of the world's boldest attempts to tackle air pollution.

From next Monday, thousands of drivers face paying a new charge to enter central London.

The aim is to deter the dirtiest vehicles in an effort to reduce diseases and premature deaths.

The initiative comes as scientists say the impacts of air pollution are more serious than previously thought.

The mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, told the BBC the threat of air pollution, which is mostly invisible to the naked eye, was "a public health emergency".

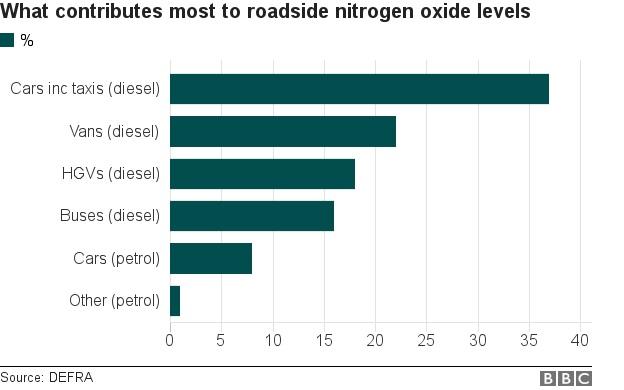

He added: "One of the things that has troubled me is that because we can't see the particulate matter, the nitrogen dioxide, the poison, you don't take it seriously."

But over the last few decades, research has revealed how gases like nitrogen dioxide and tiny particles, known as particulate matter or PM, can reach deep into the body with the danger of causing lasting damage.

Asthma attack

The most obvious effects are on our breathing - anyone suffering from asthma, for example, is more likely to be at risk, because dirty air can cause chronic problems and also trigger an attack.

"I had to stay up one night because my chest was really bad because [of] all the polluted air," 10-year-old Alfie told me. "I couldn't go to sleep and my mum had to stay awake."

"All that polluted air can hurt your lungs, it can even damage you brain, it can damage nearly everything in your body," he said.

A pupil at Haimo Primary School in Eltham, close to London's busy South Circular Road, Alfie is one of 300 children across the capital taking part in unique research.

A hot exhaust stands out in this thermal camera image

The project involves each child wearing an air-monitoring backpack, specially built by Dyson and fitted with instruments to measure nitrogen dioxide and the smallest particles, called PM2.5.

One motivation for the work is that breathing in dirty air at an early age can have implications that last a lifetime.

Research has shown that children growing up in heavily polluted streets have smaller lung capacity than those in cleaner areas - on average by 5% according to a study in London - a limitation that cannot be reversed.

Greater challenges

And air pollution can exacerbate other respiratory conditions too, including emphysema and chronic bronchitis, and lung cancer is thought to be linked as well.

Dr Ben Barrett of King's College London, who is running the backpack research, says that children born in a more polluted environment face greater challenges in life.

"It's not necessarily that there's a particular disease that they develop but their body is less able to cope with those challenges as they go into adolescence and into old age."

Another pathway to harm is opened up when the smallest particles find their way into the depths of the lungs, to the alveoli, from where oxygen is transferred into the bloodstream.

It's been established that PM2.5 particles are small enough to make that transition as well, entering the cardiovascular system and circulating throughout the body.

The risks of this include the potential for blocking the arteries, increasing the danger of stroke, along with heart disease and heart attacks.

Beyond that, there's evidence that the particles can reach the brain so researchers are investigating the potential effects on conditions such as dementia.

Body of evidence

A major Chinese study last year proposed a connection between pollution and lowered cognitive performance, while a British study published last week suggested a link to psychotic episodes in teenagers.

According to Prof Jonathan Grigg of Queen Mary University London, a leading figure in research into the effects of air pollution on children, the evidence for wide-ranging impacts is growing.

"We're absolutely certain that air pollution is associated with respiratory disease such as asthma and with cardiovascular disease with heart attacks and strokes, and in five years we'll be more certain about other conditions like dementia and obesity."

One new area of research is the hunt for an explanation for why babies in the most polluted areas tend to be born more prematurely and underweight compared with those born elsewhere.

A small study, still under way, is investigating placentas and has found black dots that look similar to pollution particles spotted in lung cells.

One of the researchers involved in the work, Norrice Liu, also at Queen Mary University, said the placenta would be expected to provide a sterile environment so the sight of black dots was a surprise.

"We know what pollution particles look like when they're in the cells elsewhere in the body particularly in the lungs, and the black bits that we're seeing in the placenta are a very similar shape and colour to those what making us think they could be pollution particles."

Their presence does not prove a link with premature birth or lower birthweight but it does suggest a possible mechanism.

Fifteen young mothers have so far agreed to donate their placentas to the study, and one of them, Rachel Buswell, told me that of all her concerns while pregnant, air pollution was not one of them.

"It's pretty scary," she said, "you protect yourself when you find out you're pregnant in as many ways as you can and that's going to be something people can't protect themselves as easily, living in London especially, it is quite frightening."