Wood wide web: Trees' social networks are mapped

- Published

Scientists have mapped the underground network of fungi that provide trees with nutrients.

Research has shown that beneath every forest and wood there is a complex underground web of roots, fungi and bacteria helping to connect trees and plants to one another.

This subterranean social network, nearly 500 million years old, has become known as the "wood wide web".

Now, an international study has produced the first global map of the "mycorrhizal fungi networks" dominating this secretive world.

Details appear in Nature journal.

Using machine-learning, researchers from the Crowther Lab at ETH Zurich, Switzerland, and Stanford University in the US used the database of the Global Forest Initiative, which covers 1.2 million forest tree plots with 28,000 species, from more than 70 countries.

Other stories you might like:

Using millions of direct observations of trees and their symbiotic associations on the ground, the researchers could build models from the bottom up to visualise these fungal networks for the first time.

Prof Thomas Crowther, one of the authors of the report, told the BBC, "It's the first time that we've been able to understand the world beneath our feet, but at a global scale."

The research reveals how important mycorrhizal networks are to limiting climate change - and how vulnerable they are to the effects of it.

"Just like an MRI scan of the brain helps us to understand how the brain works, this global map of the fungi beneath the soil helps us to understand how global ecosystems work," said Prof Crowther.

"What we find is that certain types of microorganisms live in certain parts of the world, and by understanding that we can figure out how to restore different types of ecosystems and also how the climate is changing."

Losing chunks of the wood wide web could well increase "the feedback loop of warming temperatures and carbon emissions".

Mycorrhizal fungi are those that form a symbiotic relationship with plants.

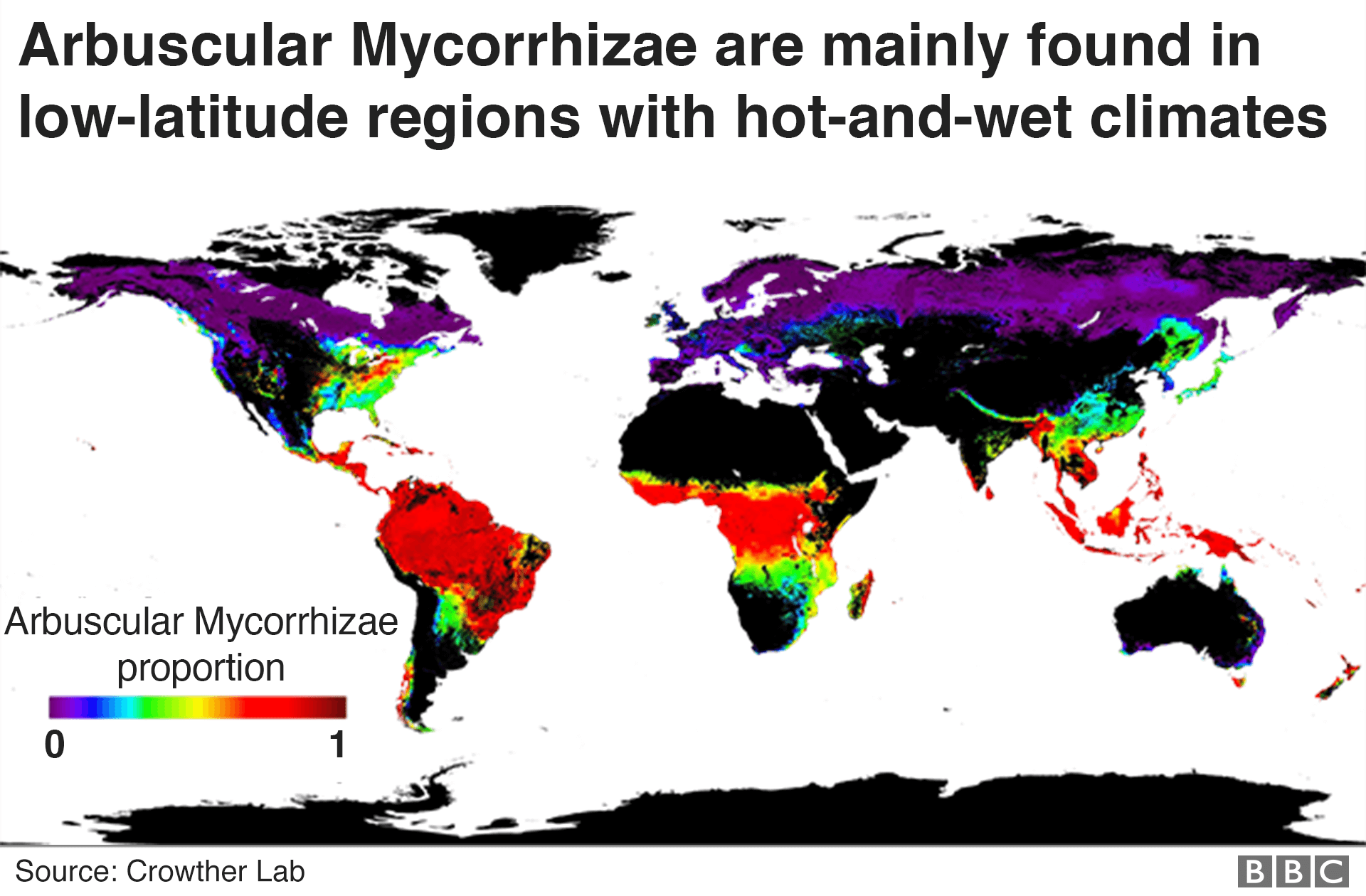

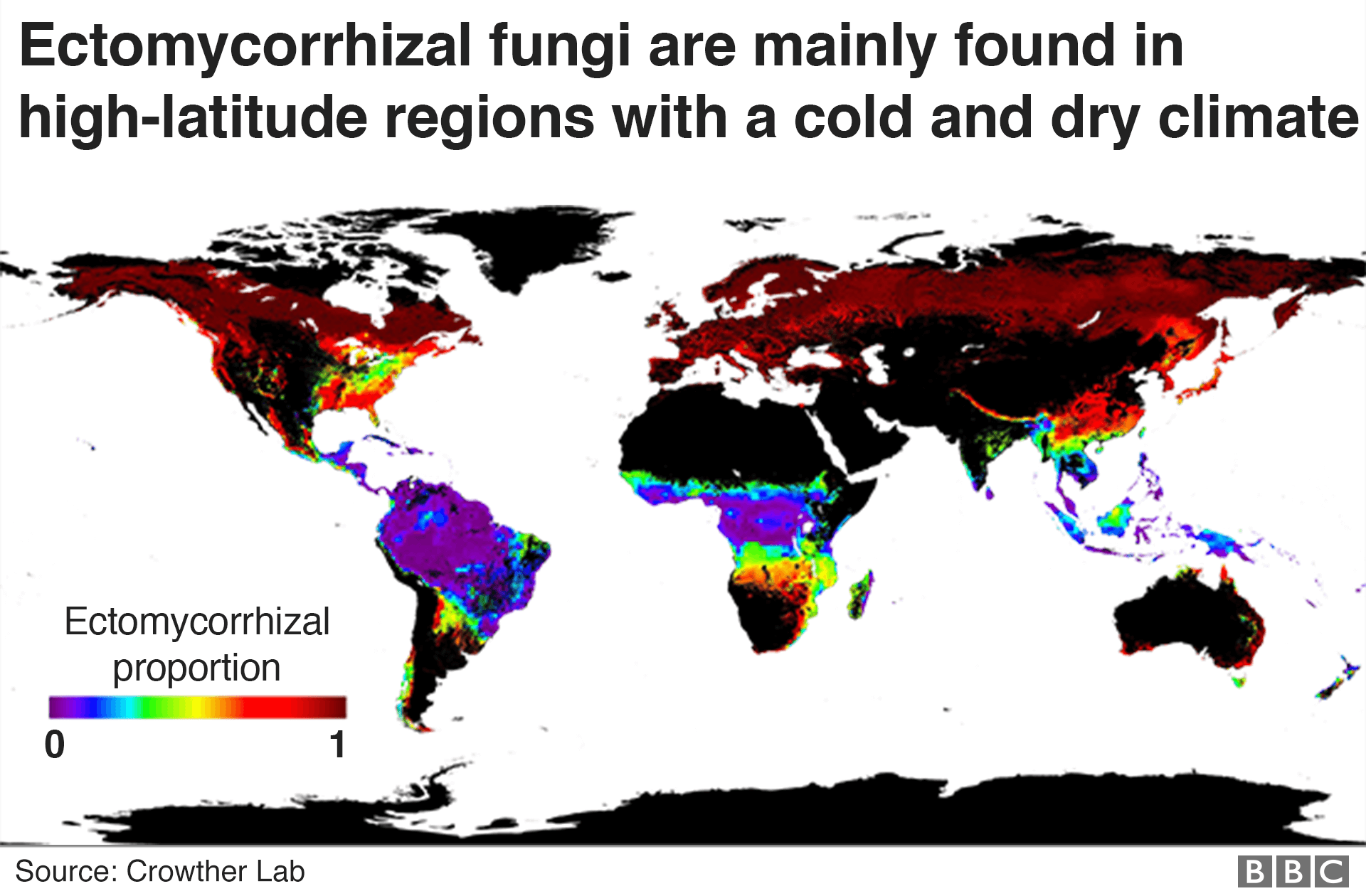

There are two main groups of mycorrhizal fungi: arbuscular fungi (AM) that penetrate the hosts's roots, and ectomycorrhizal fungi (EM) which surround the tree's roots without penetrating them.

EM fungi, mostly present in temperate and boreal systems, help lock up more carbon from the atmosphere. They are more vulnerable to climate change.

AM fungi, more dominant in the tropics, promote fast carbon cycling.

According to the research, 60% of trees are connected to EM fungi, but, as temperatures rise, these fungi - and their associated tree species - will decline and be replaced by AM fungi.

"The types of fungi that support huge carbon stores in the soil are being lost and are being replaced by the ones that spew out carbon in to the atmosphere."

This could potentially accelerate climate change.

If there isn't a reduction in carbon emissions by 2100, there could be a 10% reduction in EM - and the trees that depend on them.

The results of this finding can now serve as a basis for restoration efforts such as the UN's trillion tree campaign by informing which types of tree species, depending on their associated mycorrhizal network, to plant in what particular area of the world.

Mycorrhizal ecologist Dr Merlin Sheldrake, said, "Plants' relationships with mycorrhizal fungi underpin much of life on land. This study ... provides key information about who lives where, and why. This dataset will help researchers scale up from the very small to the very large."

Dr Martin Bidartondo, an honorary research associate with Kew Gardens, said: "Now for the first time, we have this large-scale dataset that tells us what is happening - across the globe.

"Through our daily activities we are very much counting on the carbon in the soil to stay there, and not only that, but to continue accumulating. If we create conditions through changing the type of fungi that are interacting with plants in the soil in which then those soils begin to stop accumulating carbon, or they start releasing it, then the rate at which we are seeing change will start accelerating even more."

Follow Claire on Twitter., external

- Published28 June 2018

- Published6 June 2018