Aeolus: Wind-mapping space laser is losing power

- Published

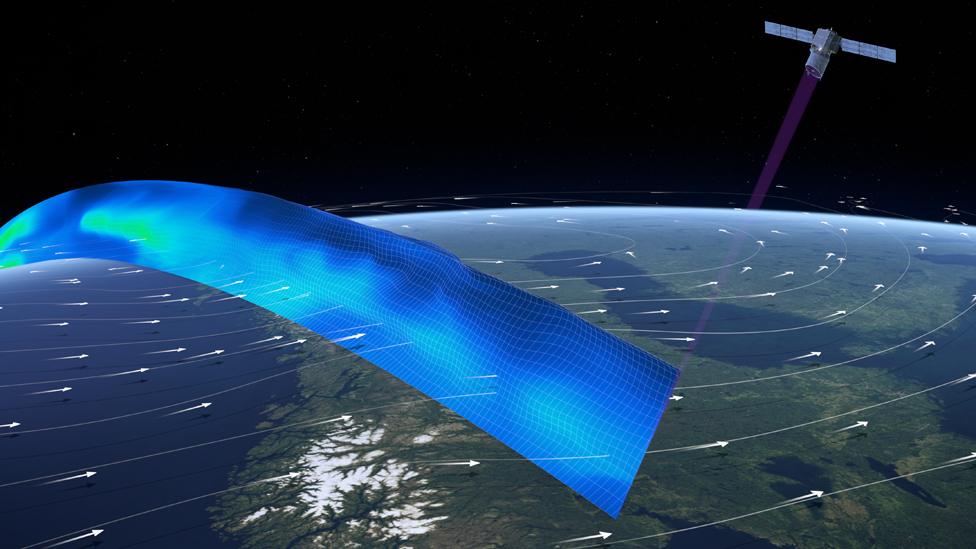

Artwork: "Aeolus has absolutely proved the principle," says Dr Florence Rabier

Europe's Aeolus satellite was launched last year to gather data to improve weather forecasts, and its observations have unquestionably proved their worth.

But the space laser is now degrading and has already lost half its power.

Engineers plan to switch Aeolus to its back-up light source in June to see what difference this could make.

If the same issues arise, the UK-assembled spacecraft may not be able to complete the minimum three years expected of the mission.

"We're losing strength in the outgoing power of about 1 millijoule per week," said Dr Josef Aschbacher, the director of Earth observation at the European Space Agency (Esa).

"We don't know why. We have some speculations but that's all.

"That's the bad news; the good news is that despite the degrading laser, the quality of the wind data is fantastic."

Dr Aschbacher was speaking here in Milan at the agency's Living Planet Symposium, external, Europe's biggest Earth observation conference.

Meteorologists need more - and better - wind data to run their forecast models

Aeolus is simple in concept: it fires a beam of ultraviolet light into the atmosphere from an altitude of 320km and catches the reflections from moving molecules and tiny particles in the air.

This gives meteorologists a handle on the direction and speed of the wind - something they can use to tighten up their forecasts.

But flying lasers in space is technically very challenging, and European engineers tried a number of ideas before arriving at what they thought was the right solution.

Nonetheless, by the time Aeolus launched in August 2018, the mission was already 10 years behind schedule.

Dr Florence Rabier is director general of the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts. It's her agency that is making most use of the data, and she's actually very upbeat about the current situation. She's told engineers not to be downhearted.

"Aeolus has absolutely proved the principle," she told BBC News.

"It's already had a positive impact in our numerical weather system. You know, most new satellites can take months, even years, to have a positive impact. The fact that Aeolus has already had an impact is very encouraging, and I can confidently say we'd like to see more of these satellites."

The expectation before launch was that wind observations from the space laser could increase forecast quality by up to 15% in the tropics and by 2-4% in the extra-tropics.

Dr Rabier won't quote numbers at this stage but says the impact in the tropics has been significant.

How to measure the wind from space

Aeolus fires an ultraviolet laser through the atmosphere and measures the return signal using a large telescope

The light beam gets scattered back off air molecules and small particles moving in the wind at different altitudes

Meteorologists will adjust their numerical models to match the information gathered by the satellite, improving accuracy

The biggest impacts are expected in medium-range forecasts - those that look at weather conditions a few days hence

Aeolus is only a demonstration mission but it should blaze the trail for future operational weather satellites that use lasers

One of the reasons Esa, its member states and the data-user community was so patient with Aeolus's development was that wind measurements in general are actually very sparse.

All manner of technologies are used to track movement in the atmosphere - from whirling anemometers (instruments for measuring wind speed) and weather balloons, to planes and satellites that infer wind behaviour by tracking clouds in the sky. But these are all limited indications that tell us what is happening in particular places or at particular heights.

Aeolus on the other hand has been gathering wind data across the entire Earth, from the ground to the stratosphere (30km). That's a first.

An indication of the value put on this information can be seen in the reaction of Eumetsat - the intergovernmental agency that manages Europe's weather satellites. It is already talking about the need for a follow-on mission to Aeolus.

"Aeolus has been a fantastic mission to learn, and to prepare for the next step," said director-general Alain Ratier.

"I have already sent a letter to Josef on behalf of the (Eumetsat) member states proposing a road map to prepare the next step, which may be a constellation or not - we don't know yet. We need to work more on the technology to take the full lessons from Aeolus."

Engineers will first need to diagnose the reasons for the degradation in Aeolus's laser.

If after that they can see a way forward to more robust technologies, Dr Aschbacher says he could well ask Esa member states for money in 2022 to begin the implementation of a follow-on mission.

Aeolus was 16 years in the making, finally launching in August last year

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external