Plastic pollution: Flip-flop tide engulfs 'paradise' island

- Published

Close to a million plastic shoes, mainly flip flops are among the torrent of debris washed up on an "unspoilt paradise" in the Indian Ocean.

Scientists estimated that, external the beaches of Australia's Cocos (Keeling) Islands are strewn with around 414 million pieces of plastic pollution.

They believe some 93% of it lies buried under the sand, say the researchers.

They are concerned that the scale of concealed plastic debris is being underestimated worldwide.

Nearly half the plastic manufactured since the product was developed six decades ago has been made in the past 13 years, say scientists.

Through failings in waste management, much of it has ended up in the oceans, with one estimate suggesting, external that there are now more pieces of plastic in the seas than there are stars in the Milky Way.

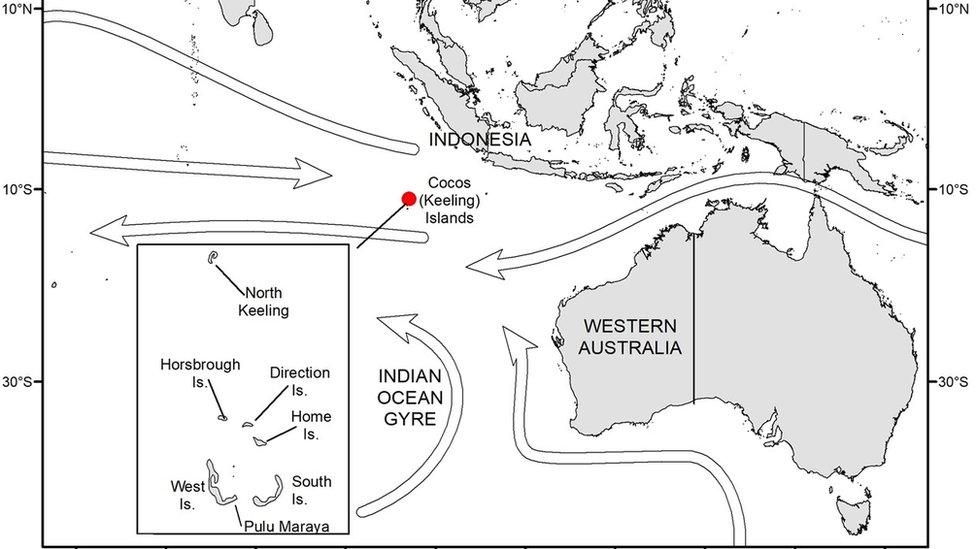

The location of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands

This latest assessment will add to the feeling that the world hasn't yet fully appreciated the scale of the problem.

The research team surveyed the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, a horseshoe chain of 26 small land masses 2,100km north-west of Australia.

Around 600 people live in these remote places, which are sometimes described as "Australia's last unspoilt paradise".

The researchers found that oceanic currents are depositing huge amounts of plastic on the beaches of these atolls.

They calculated that the islands are littered with 238 tonnes of plastic, including 977,000 shoes and 373,000 toothbrushes. These were among the identifiable elements in an estimated 414 million pieces of debris.

The scientists believe their overall finding is conservative, as they weren't able to access some beaches known to be hotspots of pollution.

Of particular concern to the authors of the report is the amount of material they believe is buried up to 10cm below the surface. This accounted for around 93% of the estimated volume.

The lead author Jennifer Lavers told BBC News that, based on what she had seen on the Cocos Islands and what she has found previously on another remote island called Henderson in the Pacific, the world has "drastically underestimated" the scale of this problem.

The finding may also help explain a significant gap in our understanding of plastic pollution.

"Over the years, over the decades, we know how much plastic we put out into the ocean. But when we've done some sampling to try and figure out how much is floating in the surface layers and things like that, there actually seems to be a bit of a mismatch between what we think we've put out there, and what we find," said Dr Lavers, from the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania.

"So there's this missing plastic where we don't actually know where it's gone. So for me, when I found out that so much of the debris on Cocos was buried, I had a little kind of a light bulb moment where I thought, perhaps this is one of the missing pieces of the puzzle."

Dr Jennifer Lavers and some of the plastic items gathered on Cocos island

Valiant attempts to clean up beaches by volunteers are literally, scratching the surface of the problem. Researchers are concerned that this wealth of buried plastic could threaten wildlife living or nesting in beach sediments, such as sea turtles and crustaceans.

"It wasn't a huge surprise to me, it's simply that the surveys done up until now have looked at the surface and its obviously a lot of time and effort to dig deeper," said Dr Chris Tuckett, from the Marine Conservation Society, who wasn't involved with the study.

"Plastic obviously breaks down into smaller pieces over time and smaller pieces will sink through the sand and settle in sub-surface layers. In hot regions, the combination of warm temperatures and high salinity is likely to make plastic items break up into pieces more quickly, although it won't disappear entirely."

Attempts to clear this concealed plastic would require major mechanical disturbance which might prove even more damaging to wildlife.

The lead author hopes that her findings will bring home to people that prevention is far better than cure when it comes to plastic pollution.

"My hope is that the Cocos provide an opportunity for people to kind of see themselves in the debris on the beach, and feel that sense of connection or ownership and realise that if they changed their behaviour, their consumption patterns, if they kind of fought for policy or legislation, if they went out and helped their neighbour, they could potentially have a beneficial flow on effects."

Dr Lavers says she has avoided plastic in her own life for the past 10 years.

"In a decade, I've never used a plastic toothbrush, I don't use plastic bags of any shape, size, denomination or source. I don't do any of these things. And yet, it's no longer a conscious decision. It's just part of my day to day life. It's just who I am.

"It's like quitting smoking. At first, it's hard, and you have to think about it. But then you don't think about it anymore. It's just part of your day-to-day actions. You just don't smoke anymore. I just don't use plastic anymore. I just don't."

The new study has been published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Follow Matt on Twitter., external