'Cryoegg' to explore under Greenland Ice Sheet

- Published

Dr Liz Bagshaw: "The models have essentially been working blind"

UK scientists head to Greenland this week to trial new sensors that can be placed under its 2km-thick ice sheet.

The instruments are designed to give researchers unique information on the way glaciers slide towards the ocean.

Dubbed "Cryoeggs", the devices will report back on the behaviour of the meltwaters that run beneath the ice.

This water acts to lubricate the flow of glaciers, and in a warmer world could increase the volume of ice discharged to the ocean.

This would push up global sea levels - potentially by as much as 7m, if all the ice on Greenland were to melt.

Scientists want to understand how fast the process could unfold.

"Our models have done a fantastic job so far in building a picture of what might happen, but they've essentially been working blind because we have so little data from the bed of the Greenland ice sheet," said Dr Liz Bagshaw from Cardiff University.

"We have some measurements from cabled instruments and from the bottom of boreholes, but we don't have enough data to figure out what's going on across the whole of the ice sheet, to determine how much of that 7m might end up in the ocean," she told BBC News.

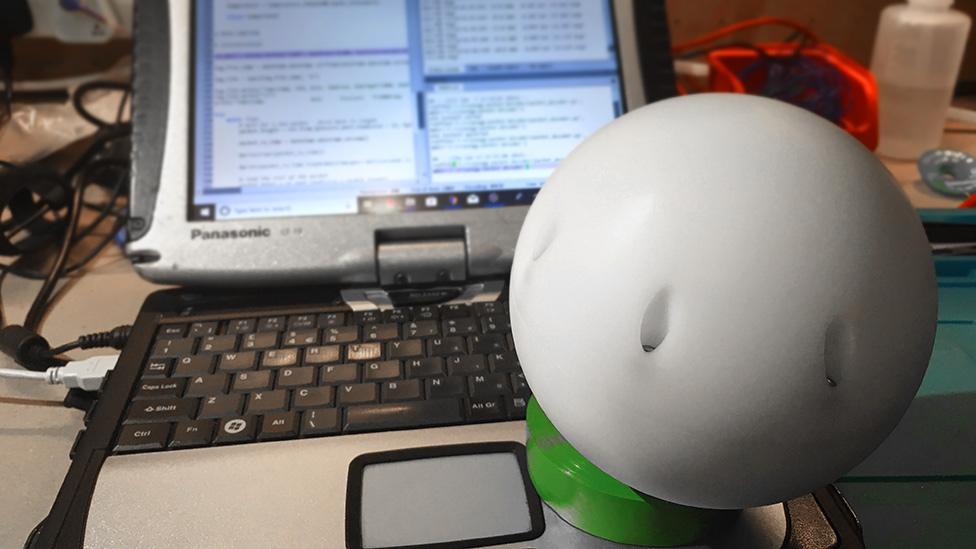

Cryoegg's shell is made from a hard, 10mm-thick engineering plastic

What exactly is a Cryoegg?

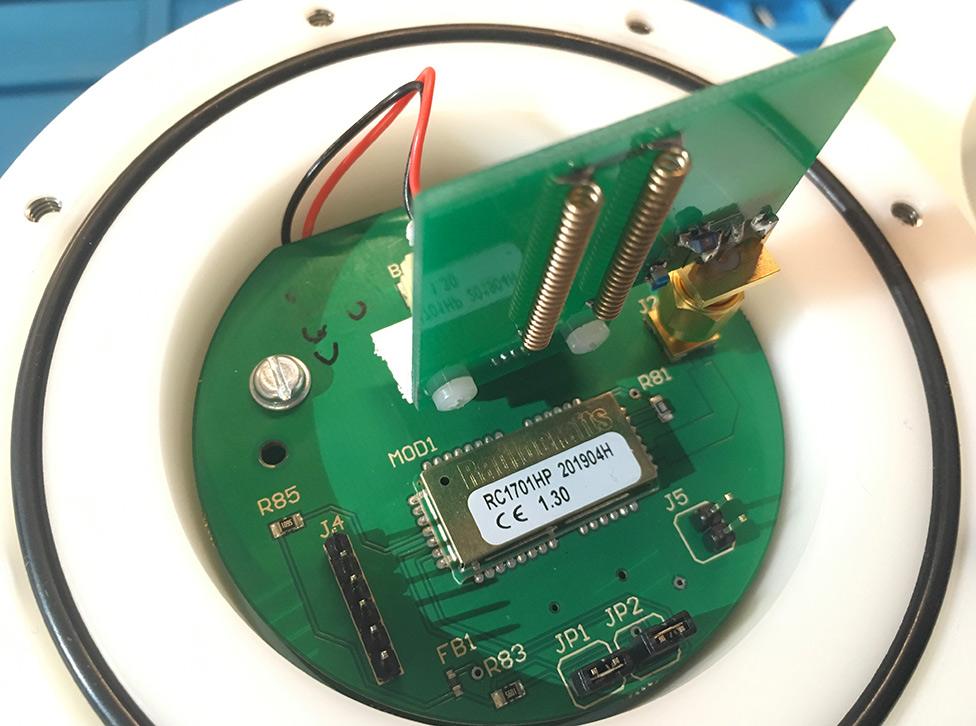

It's a 1.2kg, 120mm-diameter sphere. Inside are the electronics for three sensors, to measure water temperature, pressure and conductivity.

The egg's compact volume also contains a radio to send its data through the ice, back to the surface. A battery should enable remote working for up to a year.

The Cardiff-led team has been developing the concept for a number of years, and it incorporates some fascinating technology choices.

The radio system is taken from smart meters that would normally be reporting consumers' gas and electricity usage. This radio's low-frequency transmissions should better penetrate the thick ice.

And the antenna at the ice surface that receives those radio transmissions is held in a children's climbing frame.

"Polar expeditions require versatility," said Cardiff electrical engineer Dr Mike Prior-Jones.

"This frame is like scaffolding for kids, so when I'm not using it for the antenna I can turn it into a workbench or into seating.

"One of the joys of environmental science engineering is that it can be quite 'Heath-Robinson' - you won't immediately find everything you need ready-made in a Campbell Scientific (instrument) catalogue."

The receive antenna is held by units of Quadro - a children's climbing frame product

What will the sensor data tell scientists?

The Cryoegg will record the conditions at the base of the ice sheet. Temperature is an obvious parameter.

Pressure says something about the way water at the bed is organised, whether it's spread evenly under the ice or moving in discrete channels. The former would represent a high-pressure environment; the latter would be a low-pressure setting.

Conductivity tells scientists about the length of time any water has been in residence. Meltwater that's been present a long time will have interacted with rock and sediments, and leeched ions, increasing its conductivity.

Surface meltwater gushes down a moulin to the base of the ice sheet

Store Glacier pictured last week: Blue melt ponds can be seen collecting on the ice sheet surface

What is the significance of this information?

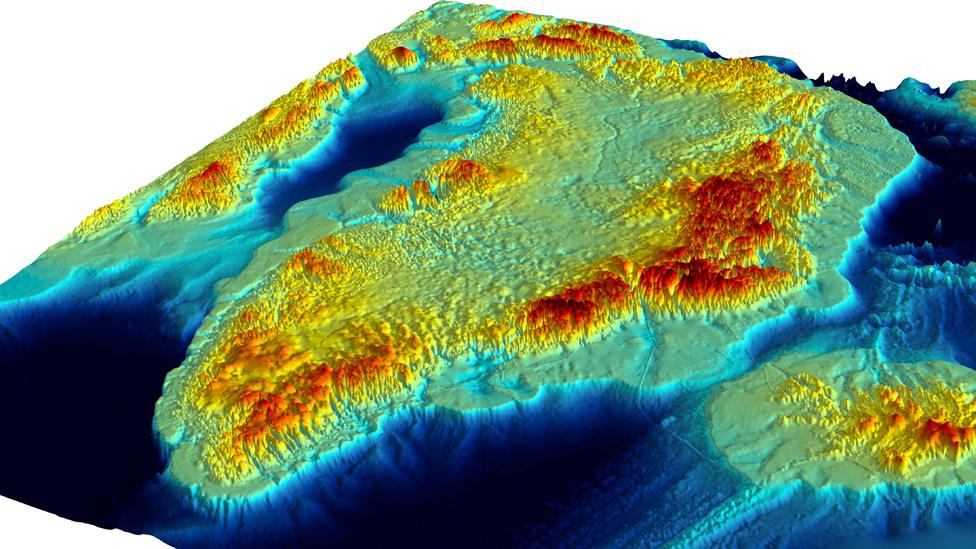

Satellites show that Greenland's glaciers speed up in summer. Great pools of meltwater are seen to collect at the surface of the ice before draining to the bed through holes known as moulin.

All this water "greases" the underside of the glaciers, speeding their passage downslope to the ocean. But the satellites see something else as well: in the warmest summers, this lubrication effect seems to wear off quite quickly. The assumption is that particularly large volumes of meltwater created early in a warm season will cut the most efficient streams and rivers at the ice bed.

"The more water you put down there, the more it will organise itself into a network," explained Dr Bagshaw.

"We've seen this with Alpine glaciers. So, instead of a thin film of water lubricating a large area, you get a series of interconnected cavities and the ice then sits back down on the rock which increases the friction. This is what we want Cryoegg to investigate."

Cryoegg's information will be used to tune models of ice sheet behaviour.

The team hopes this season's deployments will validate the latest design

Where will the Cryoeggs be deployed?

The project is working at two locations this year. One egg will go to the EGRIP site in northeast Greenland, external where a 2.5km-long ice core is being drilled. This hole won't reach all the way down to the bed in 2019, but it should get sufficiently deep to provide a good test of Cryoegg's radio communications.

A second egg will head to the RESPONDER site at Store Glacier in the West, external. The drilling operation here will access the bed. The team wants the 1.2km-thick glacier to roll over the device to see how it copes. It will be the ultimate validation of the engineering that's gone into the egg.

The eggs will be lowered on long lines to the bottom of the drill holes

What's the history of these studies?

Scientists have been trying to gather information on water movement beneath the Greenland Ice Sheet for more than a decade.

In 2008, the US space agency (Nasa) famously sent 90 rubber ducks into a moulin, external to see where the drainage hole's water went. The bath toys were never seen again!

UK scientists from Bristol University (with Dr Bagshaw participating) repeated the experiment with Xmas baubles, external the following year. The West Country scientists did have some recovery success because their moulin explorers had little radios onboard.

Researchers have also tried putting tethered instruments at the base of the ice sheet. However, some Greenland glaciers are very fast-moving and the risk is that they will quickly cut the cable bringing data back to the surface. An effective "wireless" system would therefore be a very useful tool.

A variety of approaches have been used to investigate what happens under the ice sheet

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published14 December 2017

- Published13 June 2019