Dragonfly: Drone helicopter to fly on Saturn's moon, Titan

- Published

Nasa says visiting Titan could revolutionise what we known about life in the Universe

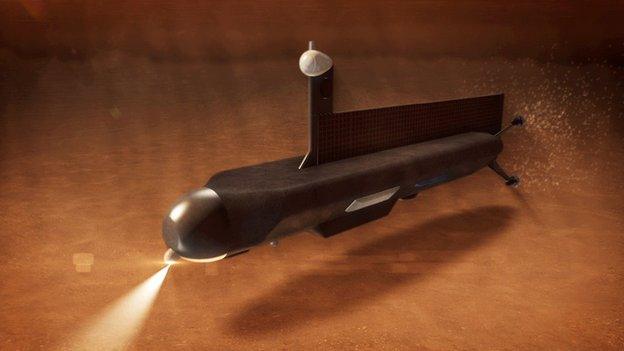

Nasa will fly a drone helicopter mission to cost $1bn (£800m) on Saturn's moon, Titan, in the 2030s.

The rotorcraft will visit dozens of promising locations on Titan to investigate the chemistry that could lead to life.

Titan plays host to many of the chemical processes that could have sparked biology on the early Earth.

The eight-rotor drone will be launched to the Saturnian moon in 2026 and arrive in 2034.

It will take advantage of Titan's thick atmosphere to fly to different sites of interest.

The Big Question: How big is space?

Dragonfly was selected as the next mission in Nasa's New Frontiers programme of medium-class planetary science missions.

It was in competition with the Comet Astrobiology Exploration Sample Return (CAESAR) mission, which would have delivered a sample from a comet to Earth.

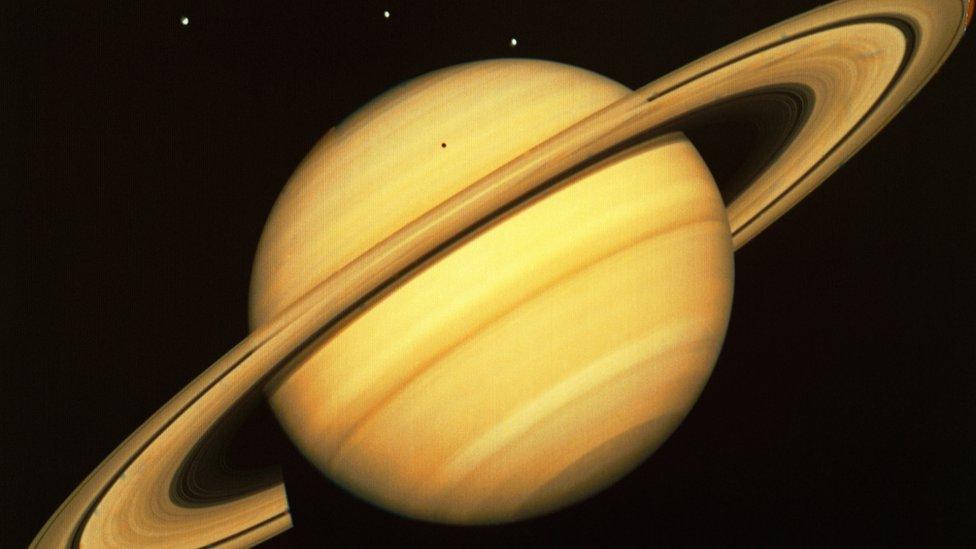

Titan is second only in size to Jupiter's moon, Ganymede, and has its own seasonal cycle, where wind and rain have shaped the surface to form river channels, seas, dunes and shorelines.

The average temperature of -179C (-290F) means that mountains are made of ice, and liquid methane assumes many of the roles played by water on Earth.

Dragonfly will first land at the "Shangri-La" dune fields, which are similar to the linear dunes found in Namibia in southern Africa.

The drone will explore this region in short flights, building up to a series of longer "leapfrog" flights of up to 8km (5 miles), stopping along the way to take samples.

"Flying on Titan is actually easier than flying on Earth," said the mission's principal investigator Dr Elizabeth "Zibi" Turtle, from Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland. "The atmosphere is four times denser at the surface than the atmosphere at the surface of Earth and the gravity is about one-seventh of the gravity here on Earth."

She added: "It's the best way to travel and the best way to go long distances so that we can make measurements in a variety of different geologic environments."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

It will finally reach the Selk impact crater, where there is evidence of past liquid water and organics - the complex carbon-based molecules that are vital for life. These may have existed together for tens of thousands of years.

"What really excites me about this mission is that Titan has all of the key ingredients needed for life," said Dr Lori Glaze, the director of planetary science at Nasa. "Liquid water and liquid methane. We have the complex organic carbon-based molecules. And we have the energy that we know is required for life.

"So we have on Titan opportunity to observe the processes that were present on early Earth when life began to form and possibly even conditions that may be able to harbour life today."

In addition to studying this "pre-biotic chemistry", Dragonfly carries instruments that can investigate the moon's atmosphere and the water-ammonia ocean thought to lie beneath its surface. It will also search for chemical evidence of past or present life.

"With the Dragonfly mission, Nasa will once again do what no-one else can do," said the US space agency's administrator, Jim Bridenstine.

"Visiting this mysterious ocean world could revolutionise what we know about life in the Universe. This cutting-edge mission would have been unthinkable even just a few years ago, but we're now ready for Dragonfly's amazing flight."

The lander could eventually fly more than 175km (108 miles) - nearly double the distance travelled to date by all Mars rovers combined.

Dragonfly will be powered by a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG), which converts the heat released by the decay of a radioactive material into electricity. While there is enough sunlight at Titan's surface to see, there is not enough to use solar power efficiently.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external

- Published19 March 2015

- Published14 November 2018

- Published27 June 2018

- Published9 March 2018