'Football pitch' of Amazon forest lost every minute

- Published

An area of Amazon rainforest roughly the size of a football pitch is now being cleared every single minute, according to satellite data.

The rate of losses has accelerated as Brazil's new right-wing president favours development over conservation.

The largest rainforest in the world, the Amazon is a vital carbon store that slows down the pace of global warming.

A senior Brazilian official, speaking anonymously, told us his government was encouraging deforestation.

How is the forest cleared?

Usually by bulldozers, either pushing against the trunks to force the shallow roots out of the ground, or by a pair of the machines advancing with a chain between them.

In one vast stretch of recently cleared land, we found giant trees lying on their sides, much of the foliage still green and patches of bare earth drying under a fierce sun.

Later, the timber will be cleared and sold or burned, and the land prepared for farming.

In other areas, illegal loggers carve new tracks through the undergrowth to reach particularly valuable hardwood trees which they sell on the black market, often to order.

What does this mean for the forest?

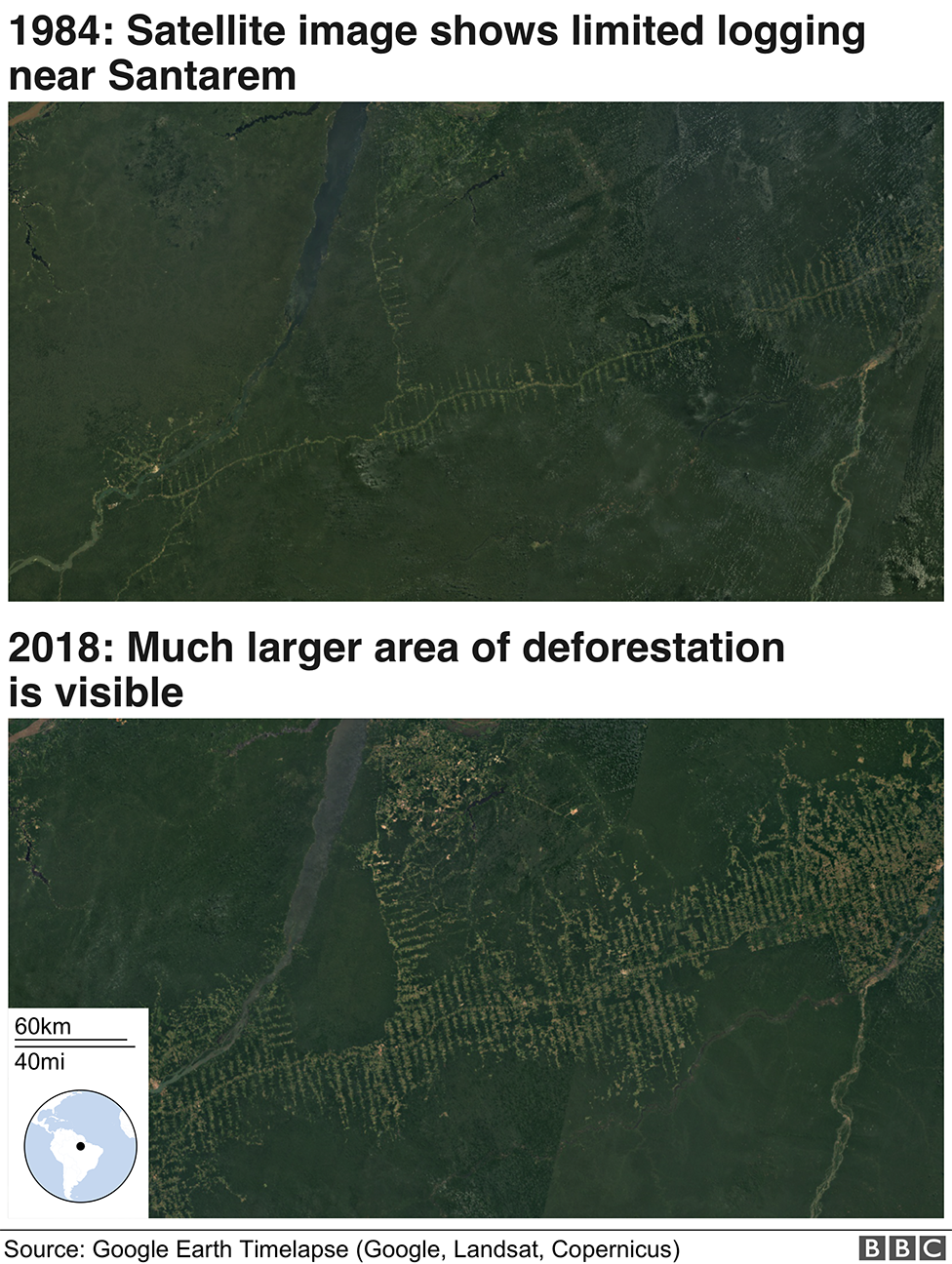

Satellite images show a sharp increase in clearances of trees over the first half of this year, since Jair Bolsonaro became president of Brazil, the country that owns most of the Amazon region.

The most recent analysis suggests a staggering scale of losses over the past two months in particular, with about a hectare being cleared every minute on average.

The single biggest reason to fell trees, according to official figures, is to create new pastures for cattle, and during our visit we saw countless herds grazing on land that used to be rainforest.

Over the past decade, previous governments had managed to reduce the clearances with concerted action by federal agencies and a system of fines.

But this approach is being overturned by Mr Bolsonaro and his ministers who have criticised the penalties and overseen a dramatic fall in confiscations of timber and convictions for environmental crimes.

Why does this matter?

The forest holds a vast amount of carbon in its billions of trees, accumulated over hundreds or even thousands of years.

Every year, the leaves also absorb a huge quantity of carbon dioxide that would otherwise be left in the atmosphere adding to the rise in global temperatures.

Jair Bolsonaro swept to power on a populist agenda

By one recent estimate, the trees of the Amazon rainforest pulled in carbon dioxide equivalent to the fossil fuel emissions of most of the nine countries that own or border the forest between 1980-2010.

The forest is also the richest home to biodiversity on the planet, a habitat for perhaps one-tenth of all species of plants and animals.

And it is where one million indigenous people live, hunting and gathering amid the trees.

What does Brazil's new policy mean?

According to a senior Brazilian environment official, the impact is so "huge" that he took the risk of giving us an unauthorised interview to bring it to the attention of the world.

We had to meet in secret and disguise his face and voice because Mr Bolsonaro has banned his environment staff from talking to the media.

Over the course of three hours, a startling inside picture emerged of small, under-resourced teams of government experts passionate about saving the forest but seriously undermined by their own political masters.

Farming organisations argue that the network of protected areas of forest is too restrictive

Mr Bolsonaro swept to power on a populist agenda backed by agricultural businesses and small farmers, many of whom believe that too much of the Amazon region is protected and that environment staff have too much influence.

He has said he wants to weaken the laws protecting the forest and has attacked the civil servants whose job it is to guard the trees.

The result, according to the environment official, is that "it feels like we are the enemies of the Amazon, when in fact we should be seen in a completely different way, as the people trying to protect our ecological heritage for future generations".

"They don't want us to speak because we'll say the truth, that conservation areas are being invaded and destroyed, there are many people marking out areas that should be protected."

So what could happen next?

The official believes the figures for deforestation could be even worse than officially recognised.

"There's a government attempt to show the data is wrong, to show the numbers don't portray the reality," he told me.

Ministers are considering hiring an independent contractor to handle information from satellite images of the region, questioning the work of the current government agency.

One million indigenous people live in the forest

Also, the rainy season is only now coming to an end, and because deforestation typically takes place in the drier months of the year, the official fears that the pace of losses could pick up speed.

"In truth, it can be even worse," he said, because many of the areas recently damaged haven't yet been picked up by satellite images.

"People need to know what's happening because we need allies to fight against invasions, to protect areas, and against deforestation."

What does the government say?

We made repeated requests for interviews with the ministers for environment and agriculture but were refused.

Earlier this year, Mr Bolsonaro, who's known as the "Trump of the Tropics", invited the US president to be a partner in exploiting the resources of the Amazon.

Last month, in an interview with BBC Brasil, the environment minister Ricardo Salles, said landowners should be rewarded for preserving forest and that developed nations should foot the bill.

And there's an assertive response when voices in the outside world call for the forest to be saved.

The president's top security adviser, General Augusto Heleno Pereira, told Bloomberg last month that it was "nonsense" that the Amazon was part of the world's heritage.

"The Amazon is Brazilian, the heritage of Brazil and should be dealt with by Brazil for the benefit of Brazil," he said.

What's the view of the farmers?

For decades, farming organisations have argued that the network of protected areas of forest, including reserves for indigenous people, is too restrictive for a developing country that needs to create jobs.

A leading figure in the farmers' union in the city of Santarem, a hub for soya and cattle, told me that other countries had cleared their trees for agriculture but now wanted Brazil not to do the same.

Vanderley Wegner said that the US and Europe, which buy produce from the Amazon region, have far less stringent controls on their forests, and that Europe "has very little forest left" anyway.

"We have to develop the Amazon. More than four million people live here and they need development too, it's a constitutional right of every Brazilian citizen," he said.