Climate change: Used cooking oil imports may fuel deforestation

- Published

- comments

Used cooking oil from Asia is being imported into Europe to make biodiesel

Imports of a "green fuel" source may be inadvertently increasing deforestation and the demand for new palm oil, a study says.

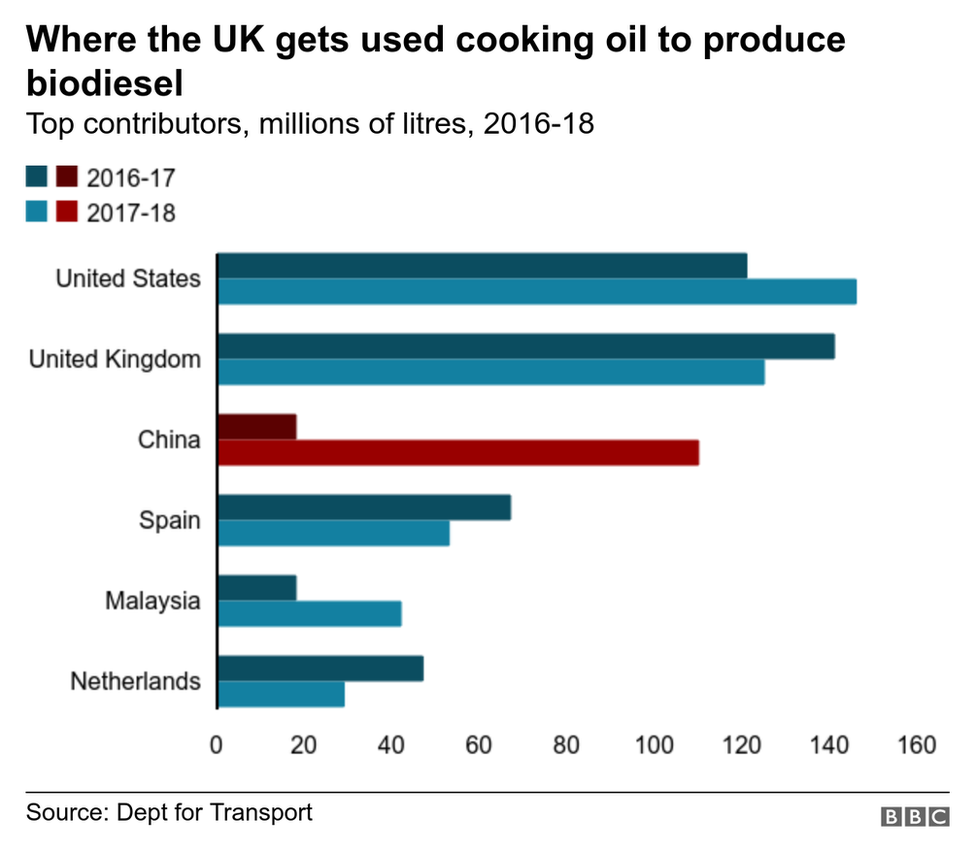

Experts say there has been a recent boom in the amount of used cooking oil imported into the UK from Asia.

This waste oil is the basis for biodiesel, which produces far less CO2 than fossil fuels in cars.

But this report, external is concerned that the used oil is being replaced across Asia with palm oil from deforested areas.

Cutting carbon emissions from transport has proved very difficult for governments all over the world. Many have given incentives to speed up the replacement of fossil-based petrol and diesel with fuels made from crops such as soya or rapeseed.

These growing plants absorb CO2 from the atmosphere and so liquid fuel made from these sources, while not carbon-neutral, is a big improvement on simply burning regular petrol or diesel.

In this light, used cooking (UCO) oil has become a key ingredient of biodiesel in the UK and the rest of Europe. Between 2011 and 2016 there was a 360% increase in use of used cooking oil as the basis for biodiesel.

Because UCO is classed as a waste product within the EU, UK fuel producers are given double carbon credits for using it in their fuels. This has sparked a boom in demand for used cooking oil that is so great it is being met in part with imports from Asia.

In the UK, the most common feedstock source of biodiesel between April and December 2018 was Chinese UCO, totalling 93 million litres. In the same period, used cooking oil from UK sources was used to produce 76 million litres of of fuel.

Now a new study, from international bioeconomy consultants NNFCC, suggests that these imports may inadvertently be making climate change worse by increasing deforestation and the demand for palm oil.

The problem arises because used cooking oil in some parts of Asia is not classed as a waste product and is considered safe for consumption by animals.

The report's authors are concerned that since it is more profitable to sell Asian UCO to Europe for fuel rather than feed it to animals, it is likely being replaced by virgin palm oil which is cheaper to buy.

"Although correlation does not necessarily equate to causation, the available evidence indicates that palm oil imports into China are increasing, in line with their increasing exports of used cooking oils," the report states.

Between 2016 and 2018, palm oil imports into China rose by 1 million tonnes, an increase of more than 20%.

"As soon as that point is reached where you can sell used cooking oil for more than you can buy palm oil, it's a no brainer," said Dr Jeremy Tomkinson who co-authored the report for NNFCC, external.

"What you are going to do if you're in Asia, you're going to sell as much UCO as you can to the EU and buy palm oil and pocket the difference."

Demand for palm oil has led to large-scale deforestation and the loss of natural habitats across Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. Between 2010 and 2015, Indonesia alone lost 3 million hectares of forest to continued expansion of palm oil cultivation.

Each hectare of forest that's converted to palm oil releases large amounts of carbon dioxide, equivalent to 530 people flying economy class from Geneva to New York according to a recent study, external.

Most of the used cooking oil that's already imported is made from palm. But it's the extra demand from Europe, say the authors, that is likely to be fuelling deforestation.

"It's irrelevant if the virgin palm is going into the biodiesel or into the animals," said Dr Tomkinson.

"If we weren't pulling that resource out of the market, no new resource would be falling into it."

The UK government rejects the idea that imports are increasing demand for palm oil. The Department for Transport says that there is no evidence showing a causative link between policies on waste-derived biofuels and increased use of virgin oils.

The department argues that they have worked hard to ensure that such indirect effects do not happen.

"Biofuels are a key way of achieving the emission reductions the UK needs and we have long been at the forefront of action to address the indirect effects of their production, including pushing the EU to address the impact of land use change," a spokesperson said.

"Last year alone biofuels reduced CO2 emissions by 2.7 million tonnes - the equivalent of taking around 1.2 million cars off the road."

Counting double

One of the key elements that's making used cooking oil so valuable is the fact that producers in the EU are given double the number of carbon credits for using the waste material. While the EU allows all countries to "double count" carbon credits for UCO, the UK is one of the few countries to put this into practice.

Palm oil imports into China have boomed in the past two years

Oil importers say the "double counting" is vital in preventing even more palm oil from entering the European market.

"Biodiesel made from waste oil is more expensive to produce; it has higher production costs," said Angel Alvarez Alberdi from the European Waste-to-Advanced Biofuels Association.

"If we don't have a policy incentive of double counting then under normal market conditions you will have the cheapest available option and that is conventional palm based biodiesel that would still be able to reach the EU."

However, the report authors say that the policy has other dangers, not just because it may be driving up demand for palm oil in Asia but because it may also be stymieing development among other alternative fuel producers, such as ethanol in the UK.

The authors want the government to review the practice and perhaps end the double credit for imported oil

Palm oil has been linked to increased deforestation in parts of Indonesia

"If it comes from outside of the EU don't let it double count unless you put in increased levels of scrutiny to verify it's not having an impact on land use," said Dr Tomkinson from NNFCC.

"If you don't do that then you only get a single credit for that used cooking oil."

Environmental groups are also concerned about the potential impact that UK and EU imports of UCO are having.

"Making biodiesel from imported UCO is no longer the environmental good it was once perceived to be," said Greg Archer, UK director of the environmental group Transport and Environment.

"There are real concerns some of these oils may not be genuinely 'used' or they may be indirectly causing deforestation. Governments need to scrutinise the source of UCO far more closely and require organisations certifying biofuel feedstocks to undertake far more rigorous and extensive checks."

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc, external