New engine tech that could get us to Mars faster

- Published

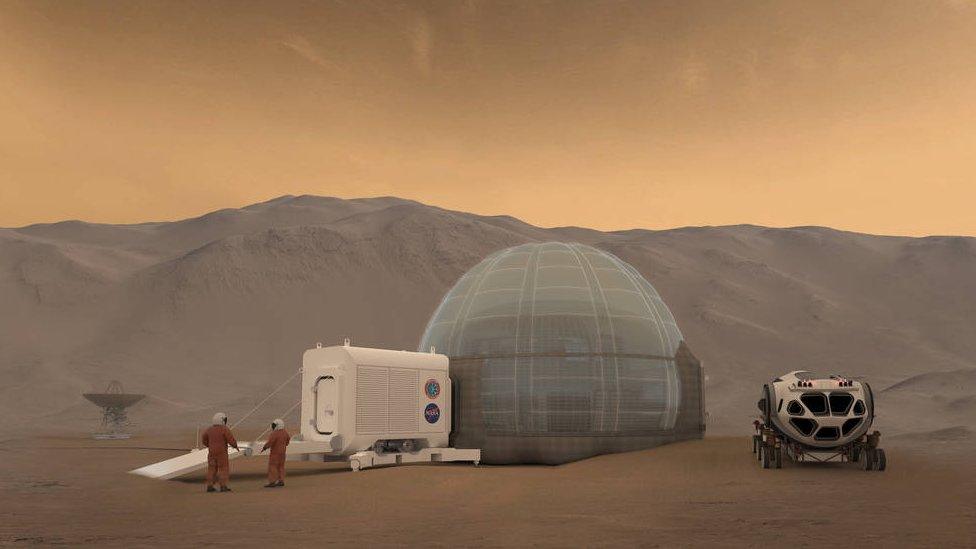

Mars Base Camp: one concept of an orbiting outpost at the Red Planet by Lockheed Martin

If we're ever to make regular journeys from Earth to Mars and other far-off destinations, we might need new kinds of engines. Engineers are exploring revolutionary new technologies that could help us traverse the Solar System in much less time.

Because of the orbital paths Mars and Earth take around the Sun, the distance between them varies between 54.6 million km and 401 million km.

Missions to Mars are launched when the two planets make a close approach. During one of these approaches, it takes nine months to get to Mars using chemical rockets - the form of propulsion in widespread use.

That's a long time for anyone to spend travelling. But engineers, including those at the US space agency (Nasa), are working with industrial partners to develop faster methods of getting us there.

So what are some of the most promising technologies?

Solar electric propulsion

Solar electric propulsion could be used to send cargo to Mars ahead of a human mission. That would ensure equipment and supplies were ready and waiting for astronauts when they arrived using chemical rockets, according to Dr Jeff Sheehy, chief engineer in Nasa's Space Technology Mission Directorate.

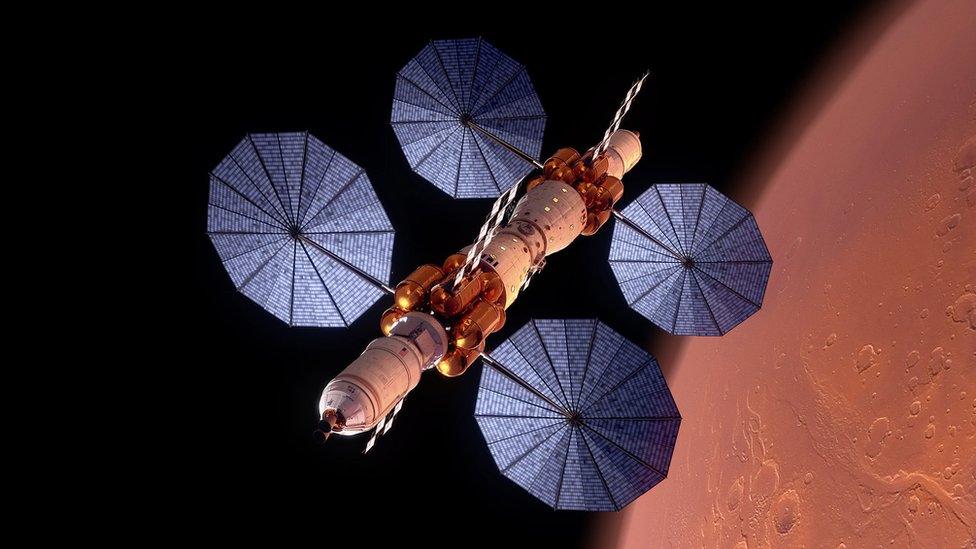

With solar electric propulsion, large solar arrays unfurl to capture solar energy, which is then converted to electricity. This powers something called a Hall thruster.

There are pros and cons. On the upside, you need far less fuel, so the spacecraft becomes lighter. But it also takes your vehicle longer to get there.

"In order to carry the payload we'd need to, it would probably take between two to 2.5 years to get us there," Dr Sheehy tells the BBC.

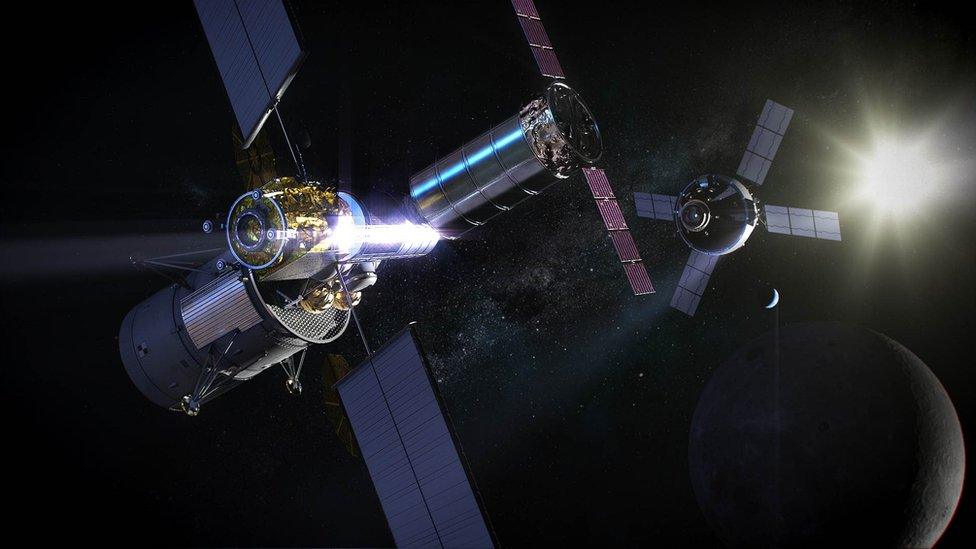

Aerojet Rocketdyne is working on a Hall thruster for the lunar Gateway

"For the kinds of outposts we'd need to build on Mars for crews to be able to survive for months, and the vehicles, you'd need a lot of cargo."

Aerojet Rocketdyne is working on a Hall thruster for the Gateway, a proposed space station in lunar orbit.

"Solar is the best because we know we can scale it up," Joe Cassidy, executive director of Aerojet Rocketdyne's space division, explains.

"We've already got these flying today on communications satellites. The power level we fly at today is 10-15kW (kilowatts), and what we're looking to do with the Gateway is to scale it up to something greater than 50kW."

Mr Cassidy said Aerojet Rocketdyne's Hall thruster will be much more fuel efficient than a liquid hydrogen and oxygen rocket engine.

But a good way to make access to space cheaper would be to have fewer launches, he explains.

"I think that solar electric propulsion is very good technology, using xenon as the propellant. But the two major drawbacks are the amount of time it takes to get there, and the size of the solar arrays," says Tim Cichan, a human spaceflight architect at aerospace giant Lockheed Martin.

Dale Thomas, a professor and eminent scholar in systems engineering at the University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH) concurs.

"Solar electric works well for smaller payloads, but we're still having trouble getting it to scale," he tells the BBC.

He thinks it could become an important alternative technology if the technical challenges can be solved. But for now, he says, there are other better options, such as nuclear thermal electric propulsion.

Nuclear thermal electric propulsion

Another idea is to use chemical rockets to lift off from Earth and to land on Mars. But for the middle part of the journey, some engineers propose using something called nuclear thermal electric propulsion.

The Orion crew module docking with Gateway in lunar orbit

Astronauts could be sent to the Gateway in Nasa's Orion capsule. The Orion crew capsule would then dock with a transfer vehicle.

Once Orion has been connected to the transfer vehicle, a nuclear electric rocket would be used to get the crew capsule and the transport module to Mars, where they link up with a Mars orbiter and lander, which are waiting in Mars' orbit.

In a nuclear thermal electric rocket, a small nuclear reactor heats up liquid hydrogen. The gaseous form of the element expands and shoots out of the thruster.

"If we can cut transit time [to Mars] down by 30-60 days, it will improve the exposure to radiation facing the crew," says Mr Cassidy. "We're looking at nuclear thermal as a key technology because it can enable faster transit times."

Dale Thomas, together with UAH, has a study contract with Nasa to design a space rocket featuring a nuclear thermal engine. He thinks nuclear thermal electric is the closest new engine technology to being ready for use.

"Some of the trajectories we run in my lab, we can get the transit time down to three months, which is still a very long journey, but it's about a third of the time that chemical propulsion requires to get us there," he says.

By being in space, astronauts are exposed to radiation. Some in the space industry fear nuclear thermal propulsion would increase that risk

Boeing is not so keen on nuclear thermal propulsion, because it worries about the effects a nuclear reactor might have on astronauts.

Mr Thomas disagrees: "This is a common misperception. The hydrogen propellant is a great radiation shield.

"The crew will be at one end of the vehicle, and the engine at the other end. As such, preliminary estimates show that the crew will get more radiation dosage from cosmic rays than from the nuclear thermal engine."

However, he admits one downside of the technology is the inability to easily test it on Earth.

But Nasa is designing a ground test apparatus that scrubs the exhaust to remove radioactive particles - making ground tests possible.

Electric ion propulsion

Another idea is electric ion propulsion. These generate thrust by accelerating ions - charged atoms or molecules - using electricity.

Ion propulsion is already being used to power satellites in space. But they produce only a low thrust - more like the power of a hairdryer - and therefore have a low acceleration. But given time, they can reach high speeds.

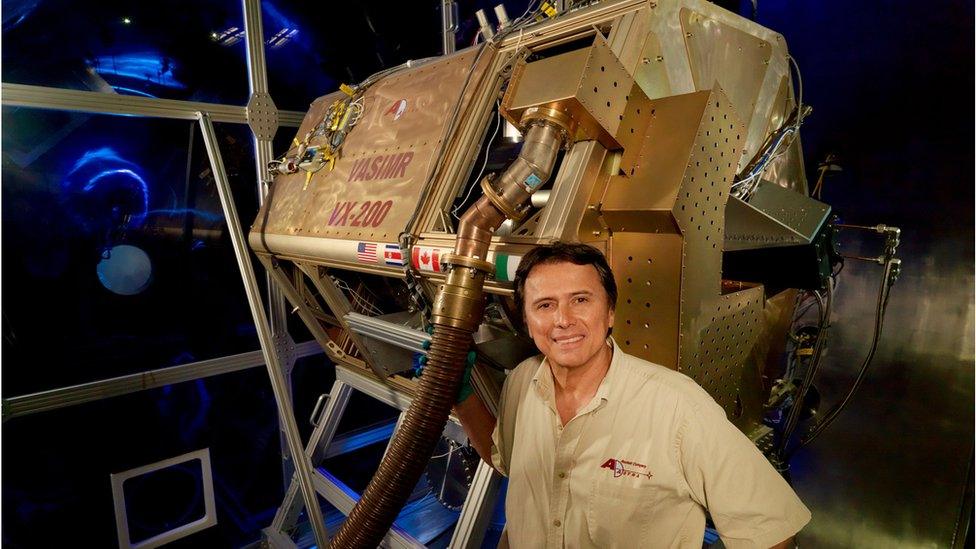

Ad Astra says it is working on a type of thruster called the Vasimr that uses radio waves to ionise and heat a propellant and then a magnetic field to accelerate the resulting soup of particles - the plasma. The Vasimr is designed to produce much more thrust than a standard ion engine.

The electricity needed can be generated in different ways. But for sending humans to Mars, the team wants to use a nuclear reactor. The Vasimr would use solar electric for smaller payloads.

Ad Astra's president and chief executive Franklin Chang Diaz, who is a former Nasa astronaut, says crewed missions need to get to Mars in less than nine months, ideally.

Former Nasa astronaut Franklin Chang-Diaz

Going to the Red Planet is much harder than going to the Moon, he says.

"The solution is to go fast," Mr Chang Diaz tells the BBC. "For a spacecraft that would weigh 400-600 metric tonnes, with a power level of 200 MW (megawatts), you can get to Mars in 39 days."

Dale Thomas believes scaling up the Vasimr will be difficult, like going from the power of a lawnmower to a space rocket. But the technology does show promise.

"If, or perhaps I should say, when Ad Astra can solve the technical challenges of Vasimr, it does appear to be the best choice for electric propulsion at the human-ferrying spacecraft scale," Mr Thomas says.

"The physics says that it should work. However, I must point out that Vasimr is still under development in the laboratory; it's a long way from being flight-ready at any scale."

Mr Chang Diaz doesn't see a problem with scaling up, it's just that there's currently no market for a 10MW engine, so Ad Astra is sticking with 200kW.

"We have a market for the 200kW engine, there's a lot of activity in low-Earth orbit and near the Moon to move cis-Earth satellites," says Mr Chang Diaz.

Lockheed Martin also thinks the Vasimr is promising technology, but it is focusing on solar electric propulsion.

The case for chemical rockets

Although the new technologies are interesting, veteran space players Lockheed Martin and Boeing both think liquid chemical rockets need to be the bedrock of any human mission to Mars.

Lockheed Martin says we already have the technology we need to get to Mars, and chemical rockets are a proven technology that worked in all the Apollo missions.

"We already have the technology to get us to Mars today," says Mr Cichan, the former system architect for Orion.

Artwork: The engines used by the core stage of the SLS were used by the space shuttle

"There are some technical challenges, but it's really about taking the technology we have, building the systems and gaining experience in flying in deep space that is the work ahead of us, as well as developing technology that will be groundbreaking in the future."

Hydrogen upper stage launchers have been used since the 1960s, and they have a high success rate, he stresses.

"Nasa's Space Launch System (SLS) has four liquid hydrogen and oxygen RS-25 rocket engines," Rob Broeren, a Boeing rocket propulsion specialist tells the BBC.

"These are shuttle heritage engines, and the advantage of the RS-25's is that they're well proven, high-reliability engines.

"The nice thing about going with highly proven technologies is that you have full confidence that they definitely work. With new technologies, they sound good on paper, but when it comes to implementing them, you will run into issues that will delay you."

When will we get to Mars?

A recent study by the Science and Technology Policy Institute, external (STPI) found that it was unlikely for human missions to Mars to follow Nasa's timetable and begin in 2033.

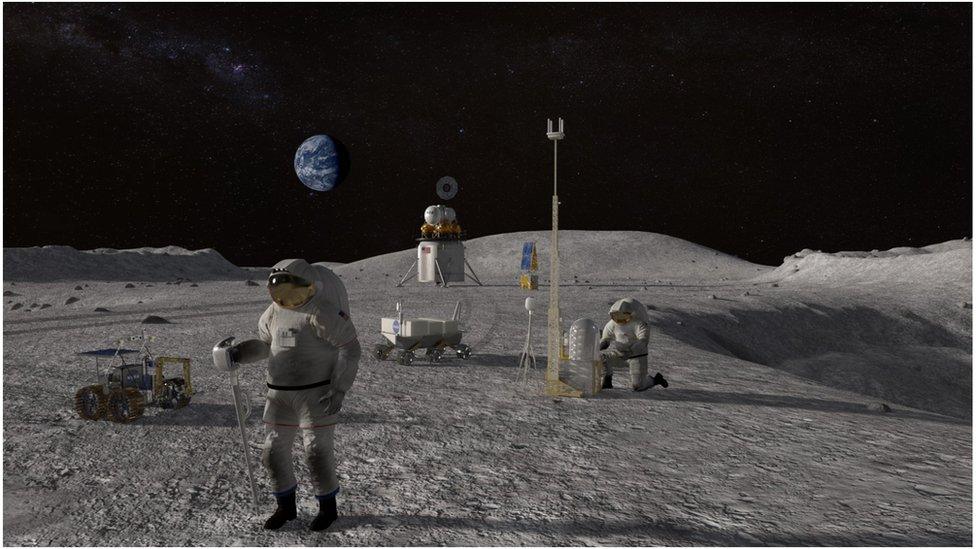

Nasa hopes to put astronauts back on the moon with the Artemis programme by 2024

Given the constraints on Nasa's budgets, STPI thinks it is much more likely that we will leave for Mars in 2039, though the White House wants the US space agency to explore the Moon first by 2024, under its Artemis programme.

Dr Paul Dimotakis, John K Northrop professor of aeronautics and professor of applied physics at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) is sceptical of the new technologies, and even chemical propulsion.

"I personally have not seen answers to technical questions of how to have enough chemical propulsion to last the long trip. It's not known for a hydrogen-oxygen rocket to last longer than six months," he says.

"We do not have a technical solution that addresses all the issues. Plus, someone has to demonstrate this before we send humans to Mars, and all of these things do not correspond to Nasa's timetable."

Related topics

- Published10 April 2019

- Published24 December 2018