Wasps: If you can't love them, at least admire them

- Published

Wasps, bees, sawflies and ants all belong to a grouping of insects known as Hymenoptera - and Gavin Broad is an enormous fan

Want to know the best way to kill a cockroach?

Well, first inject some powerful neurotoxins directly into its brain. This will make the bug compliant; it won't try to fly away and will bend to your will.

Second, slice off one of its antennae and drink the goo that comes out. For snack purposes, you understand.

And then lead it off to your lair by the stump, like a dog on a leash. You're going to bury this zombie in a hole in the ground.

But just before you close up the tomb, lay an egg on the bug. Your progeny can have the joy of eating it alive.

Dr Gavin Broad relishes these stories about how wasps will parasitise other critters. He's the principal curator in charge of insect collections at London's Natural History Museum, external, which means he's got plenty of material to work with.

Bejewelled pest control: Who wouldn't approve of the work of Ampulex compressa?

He has drawer after drawer of wasps, gathered from all corners of the globe. Ok, I can already hear you saying, "I hate wasps even if they kill roaches". But spend just a few minutes with Gavin and I promise you your views will evolve.

You'll marvel at their skill and in quite a few cases you'll be stunned (not stung) by their beauty.

That destroyer of cockroaches, for example - Ampulex compressa - has an extraordinary iridescent exoskeleton. You can see why they sometimes call it the jewel wasp.

"But every wasp is glorious," says Gavin, as he urges you to move beyond the PR spin that's got us to prefer beetles and bees instead ("Bees are just furry wasps that turned vegetarian").

Wasps have their role in Nature and it's not to pester humans in the autumn. Ignore those "yellow jackets" getting drunk on cider in September orchards; they'll soon be gone.

No, wasps have very useful functions, one of which is to keep other insects in check. Every insect you can think of probably has some wasp that will attack it. If that wasn't the case, we'd almost certainly be using more pesticides than we already do on our farms.

Gavin Broad: "Wasps are the lions of the insect world"

It's the parasitoid wasps that do this work for us and their methods - like those of Ampulex compressa - are often ingenious.

I'm fascinated by a splendid European wasp - Rhyssa persuasoria (sabre wasp). In part, I think, because I can't ever recall actually seeing one in the wild. They frequent British forests.

It has a remarkable ovipositor. That's the multi-function "hypodermic needle" at the end of the abdomen, and, in this instance, it doubles the length of the wasp to about 8cm.

The Rhyssa hunts the larvae of sawflies hiding under the bark of trees. When it senses one, it uses the ovipositor to drill through the wood fibres, to sting the grub and then lay an egg on it. Again, the wasp doesn't immediately kill its target; it uses venom merely to immobilise its prey.

"The key to success for parasitoid wasps is keeping your meat fresh," says Gavin.

Rhyssa persuasoria: From its head to the end of the ovipositor is about 8cm

He calls me into the next room, a cavernous opening full of those floor-to-ceiling museum cabinets that move on wheels. Gavin knows exactly which drawer he's after.

We don't really do "big" in the UK, so as you might expect there are even more impressive versions of Rhyssa from elsewhere in the world. Meet the aptly named Megarhyssa.

Species in this group have ovipositors that can reach 15cm in length. They store them in a bag. Megarhyssa will spend a couple of hours drilling through wood to get to its victim.

That's a lot of energy to expend, especially if you miss your target, or, as occasionally happens, another wasp comes along with a slightly narrower ovipositor and uses the exact same drill hole to replace the egg you've just laid. Hello to the group of wasps called Pseudoryhssa.

Nature works like that sometimes. Species will use every trick in the book to survive and thrive. Constant warfare.

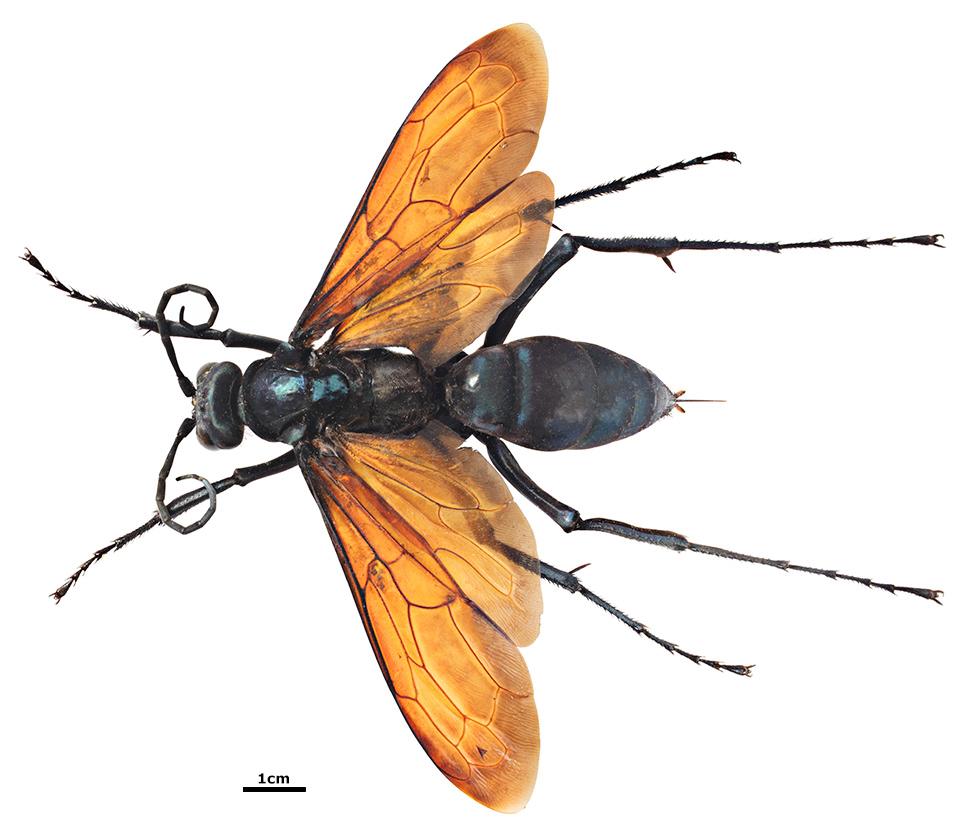

Pepsis heros: The tarantula hawks are among the largest wasps and are a fascination for schoolchildren

Gavin closes the drawer. There's even a wasp that will lay its egg inside the larva of another wasp that's already inside a caterpillar, he tells me. That sounds a bit like an entomologist's Christmas dinner: a duck inside a turkey, inside a goose.

So, what's the biggest wasp? Probably one of the tarantula hawks like Pepsis. When Gavin gives talks to schoolchildren, this is always their favourite.

You know the routine by now: the wasp lands on the spider, stings it to a standstill, and then positions an egg where the hatched grub can burrow its way inside. What's so impressive is that the larva will make sure it doesn't consume too early those organs that keep the tarantula alive.

And the smallest wasp? Well, that would be the fairyfly wasps. Creatures like Kikiki and Tinkerbella. Gavin is holding a card with some imperceptible dots on it. These wasps are about 0.2mm in length. Absolutely tiny - you need a microscope to see them.

They're so small in fact, they're probably at the very limits of what's possible in terms of miniaturised flight. And yet fly they do, to find and parasitise the eggs of other species and single-celled organisms.

The nest of a South American paper wasp, Charterginus. It looks like a leaf when hanging from a tree

My hour with Gavin is almost up but he won't let me go until he's shown me some of the most impressive nests in the NHM's collection.

"Wasps probably gave us the idea for paper," he says. They chew up wood and build the most exquisite papier-mâché structures.

Even your classic autumn annoyance, Vespula vulgaris, is an accomplished architect. The paper envelope that surrounds its comb nest will have intricate swirls and waves. The more diverse the wood sources, the more unusual the patterns.

The NHM collection even has a 1940s wasp nest made partially from wool. The wasps had recycled a nearby scarf.

Gavin's passion for his subjects is obvious and immense. So what does he say when people tell him they hate wasps. "I just cry." He laughs. "Why don't people already love wasps? They're the lions of the insect world."

The fairyflies operate at the limits of what is possible in terms of miniaturised flight (Scalebar = 0.1mm)

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external