2019 ozone hole could be smallest in three decades

- Published

- comments

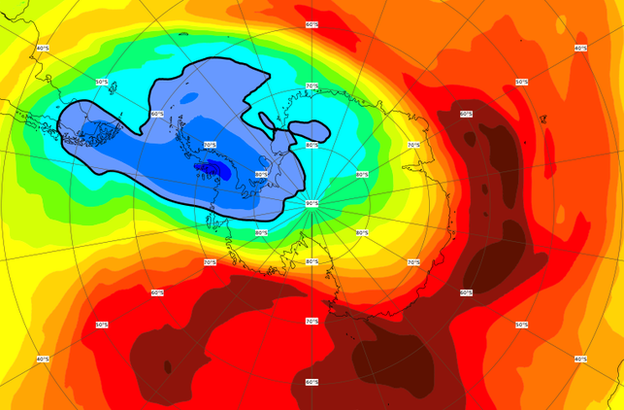

CAMS produces five-day forecasts. Currently, thinning (blue) is greatest in the region towards S. America

The ozone hole over Antarctica this year could be one of the smallest seen in three decades, say scientists.

Observations of the gas's depletion high in the atmosphere demonstrate that it hasn't opened up in 2019 in the way it normally does.

The EU's Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), external says it's currently well under half the area usually seen in mid-September.

The hole is also off-centre and far from the pole, the EU agency adds.

CAMS' experts, who are based in Reading, UK, are projecting stable levels of ozone or a modest increase in the coming days.

Ozone is a molecule that is composed of three oxygen atoms. It is responsible for filtering out harmful ultraviolet radiation from the Sun.

The gas is constantly being made and destroyed in the stratosphere, about 20-30km above the Earth.

In an unpolluted atmosphere, this cycle of production and decomposition is in equilibrium. But chlorine and bromine-containing chemicals released by human activity have unbalanced the process, resulting in a loss of ozone that is at its greatest in the Antarctic spring in September/October.

The Montreal Protocol signed by governments in 1987 has sought to recover the situation by banning the production and use of the most damaging chemicals.

This past week has seen the area of deep thinning cover just over five million square km. This time last year it was beyond 20 million square km, although in 2017 it was just above 10 million sq km. In other words, there is a good degree of variability from year to year.

The conditions for thinning occur annually just as the Antarctic emerges from Winter. The reactions that work to destroy ozone in the cold stratosphere are initiated by the return of sunshine at high latitudes.

Scientists say that while losses started earlier than normal this year, they were truncated by a sudden warming event that lifted temperatures in the stratosphere by 20-30 degrees. This destabilised the ozone destroying process.

Richard Engelen is the deputy head at CAMS. He says the small size seen so far this year is encouraging but warns against complacency.

"Right now I think we should view this as an interesting anomaly. We need to find out more about what caused it." he told BBC News..

"It's not really related to the Montreal Protocol where we've tried to reduce chlorine and bromine in the atmosphere because they're still there. It's much more related to a dynamical event. People will obviously ask questions related to climate change, but we simply can't answer that at this point."

CAMS is an EU service run by the European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), external.

It has access to a range of space-borne observations. Principal data sources include the European Metop weather satellites and the EU's own Sentinel-5P spacecraft. The four platforms all carry ozone sensors and routinely cross the pole.

Their information is combined with models of atmospheric behaviour.

The World Metrological Organization-sponsored 2018 Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion, external said a recovery of the ozone layer to pre-1970 levels could be expected around 2060.